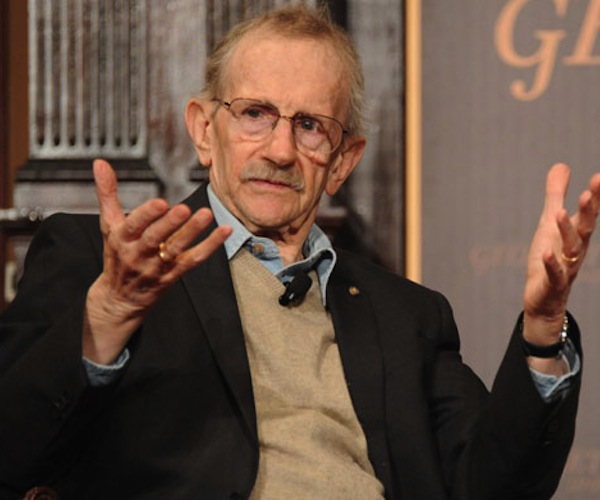

Arts Remembrance: Poet Philip Levine — A Voice of Muscle and Grit

By Robert Israel

Last Saturday, poet Philip Levine died at the age of 87 in Fresco, California. Here is a reprint of Arts Fuse appreciation of the writer, originally posted in May of last year.

Philip Levine — few poets have so eloquently captured the frustrations of looking for work and keeping a job.

At MIT’s Kresge Auditorium in Cambridge a few years back, poet Philip Levine was midway through a reading when the room was plunged into sudden darkness. The power failure, although unexpected, had a dramatic effect. It ended up enhancing the poem’s gloomy chiaroscuro narrative of a night in the 1930s when Levine and his immigrant Russian Jewish family huddled together to share dire news of pogroms in Europe:

I remember the room in which he held/a kitchen match and with his thumbnail/commanded it to flame: a brown sofa/two easy chairs, one covered with flowers,/a black piano no one ever played… — “My Father With Cigarette 12 Years Before the Nazis Could Breaks His Heart”

Levine, former Poet Laureate of the United States, Pulitzer Prize winner (in 1995 for Simple Truth), and recipient of the 2013 Academy of American Poets’ Wallace Stevens Award for lifetime achievement, turned 86 this year. He shows no signs of retiring from writing. Like his contemporaries poets Galway Kinnell (age 87) and W.S. Merwin (age 86), Levine’s voice is distinctly American. Yet what sets him apart from most of his contemporaries is his articulation of the anger, hopes, and despairs of ordinary people struggling to maintain dignity in a world that often suppresses and suffocates it.

At the core of Levine’s work one hears the rhythms and the pulses of working people, smells their sweat, feels their heartaches:

Can you image the air filled with smoke? It was. The city was vanishing before noon/or was it earlier than that? I can’t say because/ the light came from nowhere and went nowhere. – “Smoke”

…

A winter Tuesday, the city pouring fire/Ford Rouge sulfurs the sun, Cadillac, Lincoln,/Chevy gray./The fat stacks/of breweries hold their tongues. Rags, /papers, hands, the stems of birches/dirtied with words. – “Coming Home: Detroit, 1968”

…

Today the snow is drifting/on Belle Isle, and the ducks/are searching for some opening/to the filthy waters of their river./On Grand River Avenue, which is not/in Venice but in Detroit, Michigan,/the traffic has slowed to a standstill/and yet a sober man has hit a parked car/and swears to police he was not guilty.” – “Snow”

The muscle and grit of Levine’s poetry is particularly needed today. His voice is unsentimental and it is at the service of a proletarian vision that offers a valuable, if scathing, perspective on our current national malaise. Born in Detroit in 1928, his father died when he was 5 years old, leaving his family in tough economic straits. He built transmissions for Cadillac, worked for Chevrolet Gear and Axel, and drove a truck for Railway Express before quitting the city at age 26. A first generation Jewish American, his moral sensibility is rooted in the past, yet his poetry he explores the ways that history can meaningfully shape our present and future. This is especially significant now, given that his hometown of Detroit, having declared bankruptcy, sinks further into economic distress. The response of lawmakers in Lansing has been to proclaim that “Detroit dug its own hole,” at one point suggesting that the city should liquidate objects of art housed in the Detroit Institute for the Arts to pay its bills.

“The Detroit museum has always been under siege,” Levine told me in an interview during his scholar-in-residence stint at Brown University a few years ago. “I remember one time they wanted to paint over the Diego Rivera mural because it depicts a cross-section of a fetus inside a woman’s womb. Supposedly, it’s pornographic. Thankfully, they never succeeded.”

On my way to interview Levine, I spied him lumbering down a side street en route to a guest residence in Providence where we agreed to meet. But before I introduced myself, he had me in his scopes. He bristled with street smarts, sizing me up as friend or foe. Although now a retired academic from Fresno, California, he never lost his Detroit edginess, or his outspokenness.

“Just listen to the dreck pro-lifers spout and how these bigots have blocked women from gaining access to clinics for safe abortions,” he said. “It’s no different from the idiots who wanted to paint over the Diego Rivera mural in Detroit, or Father Charles Coughlin who used to rant on the radio when I was a kid in support for Hitler and puking virulent anti-Semitism. Hatred yesterday equals hatred today.”

When I commented his remarks might be construed by some as inflammatory, he shrugged it off saying, “What’s the use of having free speech unless you exercise it?”

Politics aside, few poets have so eloquently captured the frustrations of looking for work, keeping a job, especially a job mired in drudgery:

We stand in the rain in a long line

waiting at Ford Highland Park. For work

You know what work is — if you’re

old enough to read this you know what

work is, although you may not do it.

Forget you. This is about waiting,

shifting from one foot to another.

Feeling the light rain falling like mist

into your hair, blurring your vision

until you think you see your own brother

ahead of you, maybe ten places.

You rub your glasses with your fingers,

and of course it’s someone else’s brother,

narrower across the shoulders than

yours but with the same sad slouch, the grin

that does not hide the stubbornness,

the sad refusal to give in to

rain, to the hours wasted waiting,

to the knowledge that somewhere ahead

a man is waiting who will say, “No,

we’re not hiring today,” for any

reason he wants. – “What Work Is”

Levine said he actually experienced standing in that line, needing work, yet getting turned away. It is a memory that haunts him today.

To escape the burdens of work, even at a young age, Levine, like many American poets, found solace in nature, our vast land of prairies and mountains and streams. Sometimes he found peace in urban plots of soil surrounded by fences. Sometimes he wandered in foreign lands, particularly Spain, where he lived with his family during a sabbatical. Several of his poems describe walks in forests, or meanderings in a grove of trees not far from 8 Mile in Detroit, where, after dinner, he’d stand in the silence to compose poems in his head.

“I found a voice inside me,” Levine told me. “And I took joy in the physical world around me.”

The great heads of the sunflowers fall and rise/in the winds they make. The bird dares the noon light/to pick from bloom to bloom, and now I see/the tiny puffed-out breast is smeared with rose./A finch, I think, a finch for Lejan Fwint,/whose seeds beget more seeds through the long days/until the brutal air itself groans with his praise. “Praise”

When I asked him about his current poems and how it contrasts with his earlier works, Levine said: “In the past, anger was a major engine in my poetry, but now it’s been replaced by irony, it’s less elegiac, and, there’s more love.”

I asked him to share an example of this love.

“I had a student who came from the most horrific background you could imagine, from a family of abuse at home,” Levine said. “And she is one of the loveliest people you’d ever want to meet, with a kernel of life within her that just won’t be extinguished. She is someone I will write about, someday.”

These troubling times – when Levine’s hometown of Detroit teeters on lawlessness and collapse, when our fractious Congress remains unable to buoy our economy or to create jobs, when acrimony not only rules the land but stalks the streets unrestrained, Levine’s voice emerges as especially poignant.

His work personifies what Herman Melville once called “fine hammered steel.” His poems explore the best and worst of who we have been, who we are, who we are struggling to become. They are not without hope. They are not without love. They command us to listen.

Robert Israel writes about theater, travel and the arts, and is a member of Independent Reviewers of New England (IRNE). He can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com