Book Review: A Powerful Remembrance of the Cambodian Genocide — “The Elimination”

Ultimately, The Elimination is less a literary effort than an act of witness by both writer and reader.

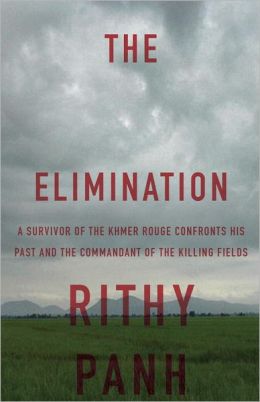

The Elimination: A survivor of the Khmer rouge confronts his past and the commandant of the killing fields by Rithy Panh with Christophe Bataille. Translated by John Cullen. Other Press, 288 pages, $22.95.

By Helen Epstein

“I don’t like the overused word ‘trauma’,” Rithy Panh writes near the beginning of his unusual and disturbing memoir The Elimination. “Today, every individual, every family has its trauma, whether large or small. In my case, it manifests itself as an unending desolation: as ineradicable images, gestures no longer possible, silences that pursue me . . . ever since the Khmer Rouge were driven from power in 1979, I’ve never stopped thinking about my family. I see my sisters, my big brother and his guitar, my brother-in-law, my parents. All dead.”

The Khmer Rouge seized control of the Cambodian capital city Pnom Penh on April 17, 1975, when Rithy was the 13-year-old son of a civil servant. They renamed middle-class, educated Cambodians like his parents “New People,” drove them into the countryside, and in less than four years had killed 1.7 million of them and others—nearly one-third of the Cambodian population. The teenager managed to survive the genocide and join members of his family in Grenoble, France in 1979.

He attended lycee, then film school, then became a successful screenwriter and documentary film-maker. Rithy wrote The Elimination with French editor and novelist Christophe Bataille, and the English translation features an unusual blend of sensibilities. It’s hard to tease out what’s personal, political, cultural, Cambodian, or French from either the understated language of this memoir or the short, episodic sections that move back and forth in time.

The central narrative centers on Rithy Panh’s quest to understand Kaing Guek Eav, generally known as Comrade Duch. Duch is an infamous perpetrator, the head of a massive torture and execution center, and a man Rithy regards as “The Commandant of the Killing Fields.” But Rithy interpolates his family’s history as well as short political and philosophical comments into his account of conducting interviews while making a film about Duch. The effect is powerful and resonant, if occasionally confusing and redundant.

Most Americans first heard of the Cambodian “Killing Fields” through the news media or the 1984 film starring Sam Waterston and John Malkovich. The latter focused less on the workings of the Khmer Rouge than on the relations between New York Times reporter Sydney Schanberg, who won a Pulitzer for his coverage of the civil war, and Dith Pran, who scouted and translated for him. The Elimination takes a much wider view of what happened in Cambodia. Hitler, Stalin, Mao, Rwanda, but particularly Nurenberg and the Hague, hover at the edges of Rithy’s consciousness as he films and talks with Comrade Duch in the prison where he is serving time for his crimes.

Readers familiar with Holocaust history will recognize Rithy’s father’s response to the impending catastrophe: “A few days before April 17, 1975, one of my father’s friends came to our house to warn him. . . . My imperturbable father refused to budge. He wasn’t afraid. A man devoted to education, he was a servant of the state and had always worked for the general good. . . . He didn’t want to leave his country . . . He assured us he would no doubt be sent to a reeducation camp for a while . . . Then conditions would start to improve . . . As for my mother and us, the children, the Khmer Rouge wouldn’t consider us important. That, then, was the analysis of an educated, well-informed man, a man with peasant origins to boot . . . a progressive who envisioned a humanistic revolution.”

Rithy describes the ensuing dispossession; deportation; dehumanization beginning with the annulment of names; the demonization of education and traditional notions of culture; slow starvation; corruption; terror; torture. “Historians today think that the revolutionaries drove some 40 per cent of Cambodia’s total population into the countryside in the course of a few days,” he writes. “There was no overall plan. No organization. No dispositions had been made to guide, feed, care for, or lodge these thousands and thousands of people . . . We sensed that the evacuation was turning bad.” The family bartered what they could but soon had nothing left. “Contrary to the popular notion, it’s not true that there’s always something left to swap. I’ve seen a country stripped completely bare, where a fork was a possession too precious to give away, where a hammock was a treasure. Nothing’s more real than nothing.”

Rithy describes how the Khmer Rouge appropriated language along with everything else. In addition to such terms as “new people” and “comrade interrogators,” Rithy learns new meanings for old terms as well as euphemisms for murder, i.e. “they were taken away to study.” He describes living and dying in abandoned rice fields, the illnesses of his family members and his own near-death, the young men and often boys who guarded and shot the prisoners.

But he returns over and over again to Comrade Duch, the organizer-in-chief of the death process. Rithy asks him “to explain everything to us: your role, the jargon you used, the organization of the prison, the confession process, the executions.” And for the most part Duch does.

Like Claude Lanzmann in his recent memoir The Patagonian Hare (Fuse interview), Rithy wants to document every detail he can discover about the criminal. He interviews, re-interviews, and obsesses about his perpetrator-subject. Driven to understand him, he returns over and over again to Duch’s face, his words, his gestures, describing the evolution of their relationship. “He was an extremely calm man, however inhumane his crimes might have been,” Rithy observes. “One could have imagined he’d forgotten them. Or that he hadn’t committed them. The question today is not to find out whether he’s human or not. He’s human at every instant: that’s the reason why he can be judged and condemned. . . . I’ll return later to the contemporary notion that we’re all potential torturers. This fatalism tinged with smugness exercises literature, film, and certain intellectuals. After all, what’s more exciting than a great criminal? No, we’re not all a fraction of an inch,the depth of a sheet of paper, from committing a great crime.”

As a filmmaker, Rithy believes in the over-riding power of the image and is less interested in words. He sometimes gives short shrift to complicated matters, such as the views of “experts” on genocide. Hannah Arendt’s idea of the banality of evil is a “seductive formula that allows all kinds of misintepretations as if there were nobody in charge and no deliberate plan. A world of gearwheels and racks and pinions and bloodstained axes.” He calls Jacques Verges to account for maintaining that there was no genocide nor organized famine in Democratic Kampuchea and for placing too much blame on the United States for both. He is “irritated” at the suicide of Primo Levi: “The idea that Levi survived deportation to a concentration camp, that he wrote at least one great book, If This is a Man, not to mention The Truce and The Periodic Table and that he threw himself down a stairwell fifty years later. . . . Primo Levi’s end terrifies me.”

Ultimately, The Elimination is less a literary effort than an act of witness by both writer and reader. It must be read in small doses, especially the parts about Comrade Duch, which I found so difficult to take in that I did not quote much from them here. I would rather quote Rithy towards the end of his memoir when he talks about why he makes art. “My films are oriented toward knowledge,” he concludes. “Everything is based on reading, reflection, research work. But I also believe in form, in colors, in light, in framing and editing. I believe in poetry. Is that a shocking thought? No. The Khmer Rouge didn’t break everything.”

Helen Epstein is the author of Children of the Holocaust and other memoirs. Her work can be found here.

Obviously a fine book and a fine review.

As an Armenian American, I cannot help but be reminded of the genocide of indigenous Christian Greeks, Assyrians, and Armenians committed by Turkey around the 1915 – 1923 era. Turkey still denies that it committed these genocides and moreover still mistreats the few remaining Christians.

For example, see this resolution by the International Association of Genocide scholars: http://www.notevenmyname.com/9.html