Visual Arts/ Book Review: “Mute Poetry, Speaking Pictures” — A Treat for Word-and-Image Fans

“Mute Poetry, Speaking Pictures” is indispensable reading for word-and-image freaks and a treat for fans of virtuoso scholarship.

Mute Poetry, Speaking Pictures by Leonard Barkan. Princeton University Press, 192 pages, $22.95.

By Gary Schwartz

It’s in the air. In 2012, Word & Image: A Journal of Verbal/Visual Enquiry brought out its 28th volume, and vol. 20 was cast onto the Internet of Word: A Journal of Visual Language. The relations between words and images, once you have begun to notice and ponder them, can take hold of you. The distinguished literary historian and critic Leonard Barkan is incurably infected; his fascination has engendered the impressive volume under review. The title is a typically brilliant phrasing, by way of Juan Luis Vives, of Horace’s old saw “ut pictura poesis,” which Barkan equally characteristically paraphrases more fully as “meaning either that a poem is or will be or should be like a picture (quite different possibilities; in fact, erit was sometimes inserted so as to nail the matter down).” These are two of the modes that Barkan masters and deploys throughout his book: reducing complex material to an evocative aphorism and/or dissecting a concept into its constituent ingredients or possibly alternate meanings—belaboring a point, as he calls it. Exact phrasing and diacritics—especially italics, as in the quotation above—play an essential role in these techniques.

Barkan’s book is not a survey, let alone a textbook, despite its touching dedication to the writer’s students, “the remarkable men and women” he taught at eight prominent universities. Some names (Leon Battista Alberti, for example) and concepts (ekphrasis) recur in all four chapters, so they are “covered” in none, while other names that an art historian would expect to find (the poet, painter, art historian—even theoretician, a high qualification for Barkan—Carel van Mander) are missing. Mute Poetry, Speaking Pictures is not a reference book in which one can be sure to find discussions of all the characters and topics germane to its wide-ranging theme.

The book is a small collection of essays probing one key issue after the other in a rambling manner with occasional outbreaks of sharp analysis. Barkan sometimes calls his book a “story,” a narrative he is constructing out of source materials, critical writings—he is admiring of and generous to his predecessors and colleagues—and stray thoughts. One of the more straightforward statements of purpose and accomplishment is to be found in the last chapter, “The Theater as a Visual Art”:

. . . the premise of these pages is that every form of literary and linguistic operation—at least in the galaxy occupied by antiquity and the Renaissance—required the analogy to the visual arts. The defining formula that Vives cites—“Painting is mute poetry, poetry a speaking painting,” along with its Horatian cousin ut pictura poesis—are only the most celebrated of the claims that rendered poetics dependent upon a theory of images. As I have suggested earlier, it is my belief that none of the foundational texts—not Plato’s Republic, nor Aristotle’s Poetics, certainly not Horace’s Ars poetica—has ever been able to define or theorize poetry without making an analogy to painting and that this analogy is not simply a heuristic device but a fundamental and often occluded step in the theoretical process.

In support of this thesis, Barkan lays before us an array of statements to which, no matter how familiar they may be, he gives imaginative new twists. The very mother of the genre has the rug pulled out from under it thus:

Ut pictura poesis is followed by a series of rather oblique elucidations. . . that leave the reader in confusion regarding what precise qualities of pictures are being urged upon poets and how the poet who took this advice would convert these pictorial properties into poetical ones.

This passage makes it clear, as Barkan shows again and again, that the seeming equation of poetry and painting in these writings is actually asymmetrical when not completely nonexistent. Concerning Socrates, who in Plato’s Republic introduces the painter as the creator of a reality of the third kind, painting a picture (3) of a specific bed that was made by a carpenter (2) on the model of “the idea of the bed” (1), Barkan writes the following:

In fact, though, Socrates isn’t really interested in pictorial matters per se. The purpose of the analogy, whatever violence it does to painterliness, is to set forth the activity of poets as sentenced to operating in the merely material realm over which it exercises its skills in a manner that is scarcely more than a reflex action. Not that poetry is his ultimate goal either. The real issue is philosophy . . . Those slippery slides of analogy are fundamental to the Nachleben of the Republic and to the history of poetics that follows from it.

In fact, none of the authors cited in the body of the book, in Barkan’s estimation, is really interested in pictorial matters. They are attempting, each in their own different and often incompatible way, to “theorize” poetry and find that they cannot do it—and this is what Barkan says unites them, despite themselves—without reference to visual depiction. “The ut pictura poesis force of Renaissance humanism owes its energy to the fact that the classical heritage of picture and of text could not be disentangled.”

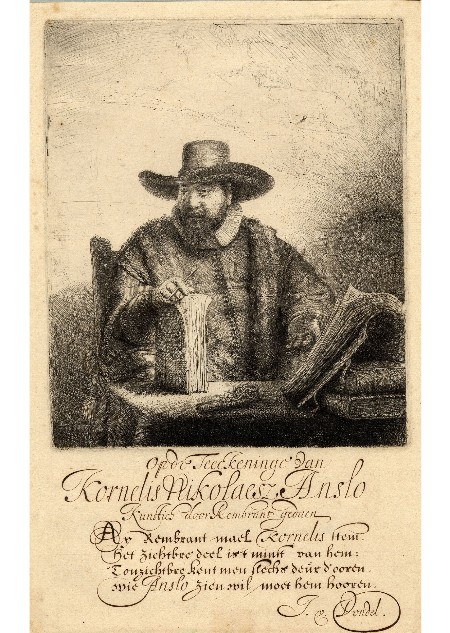

“Pictorial matters per se” place Barkan too on slippery slides. To illustrate the densely written and sometimes irresolute considerations that make up his book, I turn to the one example concerning which I am best equipped to comment, Rembrandt studies. Discussing two of Rembrandt’s portraits of the Mennonite cloth merchant and preacher Cornelis Claesz Anslo, an etching and a painting, both dated 1641, Barkan adduces the famous quatrain by the poet Joost van den Vondel:

Go ahead, Rembrandt, paint Cornelis’ voice!

The visible part is the least of him:

The invisible can be recognized only through the ears;

Who wishes to see Anslo must hear him.

(Barkan’s Dutch transcription has eight departures from the credited source. His version I found on a Mennonite Internet site; he should have consulted the inestimable Digital Library of Dutch Literature, which reproduces the publication he cites, vol. 4, p. 209 of De werken van Vondel. Forgive the pedantry, but I think the punctilious Barkan would appreciate the correction.)

In the usual reading, which Barkan follows, the poet is said to be urging Rembrandt to do something that he had failed to do so far—painting Anslo’s voice. This may be so; poems on portraits often deplore the lack of breath or speech or movement in a portrait. As Barkan sees it, following Jan Emmens, the poem addresses the print, which shows Anslo pen in hand, holding one book and pointing at another.

Rembrandt, Portrait etching of Cornelis Claesz Anslo, impression of the second state on large paper, with poem by Joost van den Vondel in calligraphy attributed to Willem van der Laegh. Signed and dated Rembrandt. f 1641. London, British Museum

The story Barkan tells about the Anslo portraits fits seamlessly into the larger narrative of his chapter, “Visible and Invisible”:

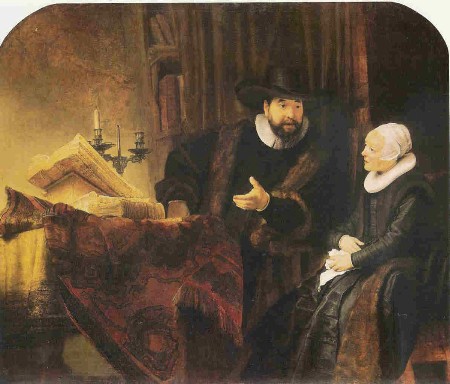

But then, Rembrandt seems to have sought the last word (or picture) by portraying Anslo again, this time in oil. Clearly, the subsequent painting does make efforts to compensate by placing the subject in some sort of conversation: his mouth is more open, his hand gesture is more directly demonstrative . . .

Rembrandt, Portrait of the Mennonite cloth merchant and preacher Cornelis Claesz Anslo and his wife Aeltje Gerritsdr Schouten (dates unknown). Signed and dated Rembrandt f. 1641. Berlin, Gemäldegalerie

This representation of events cannot be taken literally. The decision to have Anslo portrayed in paint with his wife—at 176 x 210 cm., one of the largest of Rembrandt’s paintings—was not Rembrandt’s. It was not a jeu d’esprit of the painter but a major project, on which he worked for more than a year and would never have begun without a commission and a hefty advance. The details of the composition would have to have been discussed with the patron-sitter, if only to determine the poses. Concerning the sequence in which the etching, the poem, and the painting came into being we are in the dark.

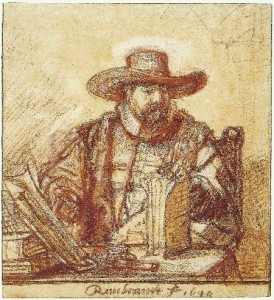

Rembrandt, Portrait drawing of Cornelis Claesz Anslo, indented for transfer to the etching plate, in red chalk. Signed and dated Rembrandt f. 1640. London, British Museum

Rembrandt, Portrait drawing of Cornelis Claesz Anslo, in the pose adopted for the painted portrait of Anslo and his wife. Signed and dated Rembrandt f. 1640. Paris, Musée du Louvre

The issue is complicated further by the existence of two drawings ignored by Barkan, one for the etching above and one for the painting below that. Both are dated 1640, suggesting that the etching and painting of 1641 were made in tandem rather than successively. Where does Vondel’s poem fit in then? These are not the only art-historical particulars that ruffle the story. What are we to make of an impression of the etching in the British Museum with a transcription of Vondel’s poem whose title says that it comments on Rembrandt’s drawing of Anslo or of two other poems on the etching, one of which does not refer at all to word-image issues and the other only glancingly? These pieces of evidence create even more uncertainty than we are vouchsafed by the author. Barkan senses this and admits to doubt concerning his interpretation of the painting. He declines, however, to relinquish the idea that the monumental double portrait in Berlin was painted in response to Vondel’s rather conventional verse. He now substitutes another reading of “the Rembrandtian riposte,” with even higher leverage:

The painting’s composition signals an increased role for the volumes now luminously arrayed on the worktable. If Vondel wishes to claim that this is a competition with one particular individual’s body and his voice, Rembrandt seems to be moving toward an opposition with more enduring substance: between the authority of the Book and that of the preacher who expounds it.

This is an intriguing possibility, but is it crude to wonder how in the world one is ever to substantiate it? The pages on Rembrandt in Mute Poetry, Speaking Pictures make me wonder whether the surviving art works and poems can be arranged into any kind of “story” that is not sheer projection.

Reading Barkan is sometimes a great pleasure, sometimes a bit of a pain. Both sentiments are sparked by the same source, the author’s inveterate tendency to qualify his statements with provisos and exceptions, emphases and accolades, metaphors and musings, until a thought that might have found expression as a declarative sentence or two accretes clause after clause, dash after dash, circles within circles. Most are spot on and a delight to parse, but some are gratuitous, overstated or, I am sorry to say of a writer with such academic panache, inelegant. In too many sections, I gave up trying to follow the argument and simply read each sentence as a stand-alone product, savoring the one and shaking my head at the other.

Mute Poetry, Speaking Pictures is indispensable reading for word-and-image freaks and a treat for fans of virtuoso scholarship.

Gary Schwartz was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1940. In 1965 he came to the Netherlands with a graduate fellowship in art history and stayed. He has been active as a translator, editor, and publisher; teacher, lecturer, and writer; and as the founder of CODART, an international network organization for curators of Dutch and Flemish art. As an art historian, he is best known for his books on Rembrandt: Rembrandt: all the etchings in true size (1977), Rembrandt, his life, his paintings: a new biography (1984) and The Rembrandt Book(2006).

His Internet column, now called the Schwartzlist, appeared every other week from September 1996 to April 2007 and has been appearing since then irregularly.

In November 2009, Schwartz was awarded the coveted tri-annual Prize for the Humanities by the Prince Bernhard Cultural Foundation of Amsterdam.

Responses always welcome at Gary.Schwartz@xs4all.nl.

Tagged: Leonard Barkan, Mute Poetry, Princeton University Press, Schwartzlist

Thanks for the pluglink, Gary! Barkan’s book reminds me of a prof. I had who taught the History of Art Criticism from the Middle Ages through the Baroque; she was a medievalist. When the class finally got past Michelangelo she announced that from the moment the visual arts were considered mere extensions of Literature in the Mannerist era, the History of Art was over, and so was the course…

Cordially

Wölfflin Jack

Euro-Arts Editor

WOID, a journal of visual language