World Books Review: “The Twin” — Isolation Made Compelling

A brilliant Dutch novel that explores the connections to the disconnected.

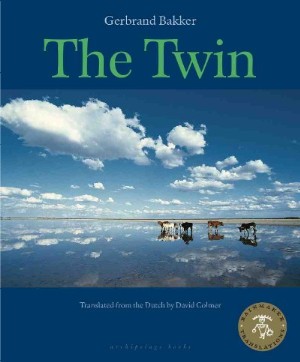

The Twin By Gerbrand Bakker

Translated from the Dutch by David Colmer. Archipelago Books, 343 pages.

Reviewed by Tommy Wallach

It isn’t easy to write a compelling novel about loneliness, for the simple reason that loneliness is boring. It makes for something of a paradox: the feeling of aloneness, both literal and figurative, counts among love, loss, and taxes as one of those ineluctable human experiences. We need to read about loneliness in order to understand our own; we connect to the disconnected, which hopefully keeps us from jumping off a building when we get dumped, or when a loved one dies. Yet both love and loss involve dramatic action of some sort; aloneness, on the other hand, is generally characterized by stasis.

In “The Twin”, Dutch author Gerbrand Bakker has accomplished the difficult task of rendering the static solitude of his protagonist into something dynamic and readable. In a prose style unhurried but visceral (translated without a false note by David Colmer), he creates and explores a loneliness that any reader would recognize as his own.

The loner in question, Helmer works on his family farm somewhere in the Dutch countryside. Though he lives with his sickly father, whom he loves and hates in equally depthless measure, Helmer suffers from a terrible sense of loneliness, which springs from a wound decades old: the death of his twin brother, Henk, killed in a car accident when the boys were still teenagers. Henk was their father’s favorite, and after he died, Helmer was compelled by guilt into leaving university and returning home to work on the farm.

The novel begins more than thirty years later. Helmer has moved his father into an upstairs bedroom so that they don’t ever have to speak, and a hooded crow has taken up residence in a tree, a sure sign of the infusion of loneliness into every aspect of Helmer’s existence. Here’s Helmer hanging out with his one friend, Ada, who lives next door. As she talks, his gaze wanders towards the window and he ponders his sense of alienation:

It’s a Saturday, the sun is shining and there’s no wind. A clear December morning with everything very bare and sharp. A day to feel homesick. Not for home, because that’s where I am, but for days that were just like this, only long ago. Homesick isn’t the right word, perhaps I should say wistful. Ada wouldn’t understand. Not coming from here, she doesn’t remember days long ago that were just like this, here.

The main action of the novel begins when Riet, the woman responsible for the car crash in which Henk was killed, sends a letter to Helmer. Riet, who was Henk’s girlfriend at the time of his death, initially seems to be seeking out a romantic connection, but eventually reveals that she’s hoping that her son, a teenager with—who would have guessed?—emotional problems, can work on Helmer’s farm for a few months.

Author Gerbrand Bakker holds up his healthy literary bloom.

Over the course of this boy’s stay at the farm, Helmer finally reengages with the world around him. It is the pacing of this reawakening that is the real wonder of Bakker’s book, accomplished through an insight into his protagonist that renders even the hoariest concept fresh, and the most banal event revelatory. For example, it eventually becomes clear that Helmer is gay, yet no line is drawn between his sexuality and his loneliness. Instead, Bakker subtly links Helmer’s orientation to his relationship with his twin, whose sexual awakening with Riet eventually alienated the two brothers.

Particularly poignant is a flashback from Helmer’s youth that he is constantly reliving, the day his twin told him they could no longer share a bed. It is the figurative death that prefigured the literal one, a trauma experienced backwards and so healed when Riet’s son (who is also named Henk) slips into bed with Helmer one night.

Everywhere are these thematic ripples, quiet but resonant. Helmer keeps two donkeys, whose surface similarity provides a self-indulgent recreation of his childhood relationship with his brother. Midway through the novel, he almost drowns beneath a pig, and is saved by Riet’s son. The hooded crow eventually disappears, but not before claiming its victim.

When a man from Helmer’s past finally convinces him to leave the farm behind, spiriting him off so suddenly that it practically feels like a deus ex machina, the reader doesn’t feel dissatisfied. Again, Bakker eschews the cliché; instead of ending the story when Helmer finds love, he goes a step further. Like everyone, Helmer still feels his loneliness acutely at times, even when he isn’t actually alone. In the final scene, Helmer leaves his lover in a hotel room and goes out to wander the empty streets and watch the sun set:

I know I have to get up. I know that the maze of paths and unpaved roads in the shade of the pines, birches and maples will already be dark. But I stay sitting calmly. I am alone.

I am alone, he tells us. Yet we feel the less so for that.

Tagged: Archipelago-Books, Books, David-Colmer, Featured, Gerbrand-Bakker, The-Twin, Tommy-Wallach