Film Review: Still in Bondage — Movies About Slavery, post Civil War

Two new films explore the provocative premise that slavery in America didn’t end after the Civil War.

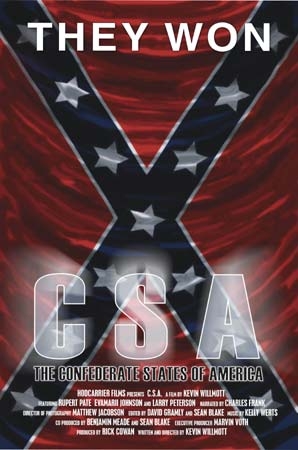

Manderlay, directed by Lars von Trier and CSA: The Confederate States of America, directed by Kevin Willmott

By Betsy Sherman

In the trailer for Danish director Lars von Trier’s 1991 Zentropa, Max von Sydow tries to hypnotize us while we watch woozy visuals of train tracks. Von Trier, one of world cinema’s foremost provocateurs, has long been interested in mind control, power and surrender. His movies are filled with victims and victimizers. Even when Von Trier appeared in a documentary — Jorgen Leth’s riveting Five Obstructions — he was shown gleefully torturing the elder Leth by challenging him to remake one of his ’60s short films five times, under five sets of restrictions.

Von Trier’s 2003 Dogville was the first in a projected trilogy that’s sarcastically called USA — Land of Opportunities. That film, which was often brilliant in etching the banality of evil, brought a damsel in distress to an insular 1930s Colorado town. What started as a homespun Our Town turned into “The Lottery.” In Von Trier’s new Manderlay the protagonist Grace (then played by Nicole Kidman, now by Bryce Dallas Howard), having survived enslavement in Dogville, comes upon a plantation in 1933 Alabama at which slavery of black people persists, as if encased in amber before the Civil War.

And if the oppressed weren’t complicit in their oppression — well, then it wouldn’t be a Lars von Trier movie. Playing with fire is the director’s passion. But although Manderlay is an interesting film — for all its cynicism, it is occasionally astute in its observation of human nature — it’s not a very important film. It says more about the way Von Trier treats his characters as chess pieces than about race or America.

For Manderlay, Von Trier and his creative team employ the same minimalist means as in Dogville: the action takes place on a practically bare soundstage, with white lines and block lettering indicating locations, and structures lacking one or more walls. The actors are filmed in a cinema-verite style, and the editing is full of jump-cuts. John Hurt returns as the unseen narrator, a (British) voice of authority who reads from a quaintly formal storybook text.

At the end of Dogville, Grace reconciled with her gangster father (James Caan) and used the family’s power to retaliate against her tormenters. In the new film, Grace wants to use this power to emancipate Manderlay’s slaves. To her father, it’s a “local matter” (Caan’s role is now played by Willem Dafoe, erstwhile civil rights crusader of Mississippi Burning). Grace maintains that since whites brought the Negroes over from Africa, freeing them is a “moral obligation.”

The cotton plantation’s matriarch, Mam (Lauren Bacall), dies that very day. Grace decides to stay, and asks her father to leave his lawyer and a few gunsels. She imposes a new order, making the former slaves property owners and Mam’s heirs indentured servants. Grace assures everyone that she and her security force will stay “until the first harvest is home.” After all, it shouldn’t take long to bring democracy to Manderlay. Parallels to George W. Bush and Iraq are not coincidental.

Grace’s good intentions are expressed in this stirring exchange with Manderlay’s majordomo, Wilhelm (Danny Glover). Wilhelm: “As slaves we took supper at seven. When do men take supper when they’re free?” Grace: “When they’re hungry.” The transition, however, proves to be more complicated, especially since Grace is so uninformed about her milieu.

Grace sets about raising the self-esteem of the former slaves (Manderlay’s whites are marginal characters in the drama). Von Trier, by casting Grace in this social worker mold, puts her in line with characters in his previous films that had the chutzpah to impose their grandiose vision upon the community (such as Paul Bettany’s Tom in Dogville). As soon as narrator Hurt intones lines like “slowly the subject of Grace’s edifying discourse dawned on them,” we know Grace is in for a tumble.

But the director does more than laugh behind Grace’s back. He allows Grace to have sexual stirrings — Von Trier’s women generally aren’t sexual beings by choice — but makes her desire the catalyst to her downfall. Grace is attracted to Timothy, a handsome former slave who stands out from the others because of his African accent and defiant attitude. This “homme fatal” is played by Isaach de Bankole, an erotic icon of European cinema. He and Howard have a sex scene that’s probably supposed to be more shocking than it actually is (unless we’re thinking of her as Opie’s daughter).

Howard has an all-American-girl solidity that’s appealing, even in Grace’s more humiliating moments. Glover deftly handles the role of the Uncle Tom (with a dark secret) who keeps cautioning Grace that “we ain’t ready” for freedom. Aside from him and De Bankole, the black cast is made up of British and American theater actors.

The action winds up with a geometrically, if not dramatically, satisfying act of cruelty that proves things have come full circle. Grace ambles off toward part three of the trilogy, though in the light of Von Trier’s recent “Statement of Revitality,” in which he announced that he is, yet again, reevaluating his career, it may never be staged.

Manderlay ends with David Bowie’s scathing Philly soul diatribe, “Young American,” playing over a montage of archival photos of African-American history and suffering. Maybe he should have ditched Bowie and played a cut from the Hair soundtrack, “Abie Baby,” which backhandedly thanked Lincoln, the “emanci-mother(explitive)-pator of the slaves.”

In the extraordinary new mock-u-mentary CSA: The Confederate States of America, Abraham Lincoln was never assassinated, because he was too busy trying to escape to Canada via Harriet Tubman’s Underground Railroad to go to the theater. He is shown in a faux newsreel as an elderly man with a broken spirit, remembered as “the man who lost the War of Northern Aggression.”

CSA, which imagines American life from the late 19th to 21st century as if the South had won the Civil War, is both hilarious and chilling. The commodification of blacks (and other non-whites, too) as slaves is shown to have driven the economic as well as the social history of the nation. Director Kevin Willmott combines poker-faced testimonies with convulsively funny faked movie clips (the CSA‘s Hollywood romanticized the doomed Northern cause in the lush A Northern Wind) and TV commercials (“RUNAWAY” is a show in the style of COPS; The Shackle is a product that every slave owner should have).

In the CSA, the white man is unquestionably master of his domain (in fact, women still don’t have the vote). Willmott’s film is more engaged, and engaging, than Manderlay, and serves up heaps more of food for thought.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for The Boston Globe, The Boston Phoenix, and The Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in Archives Management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.