Opera Album Review: “Judita” — A Stirring Modern Croatian Opera of Faith, Siege, and Beheading

By Ralph P Locke

In its first commercial recording, Frano Parać’s Judita wrings compelling drama out of the biblical tale.

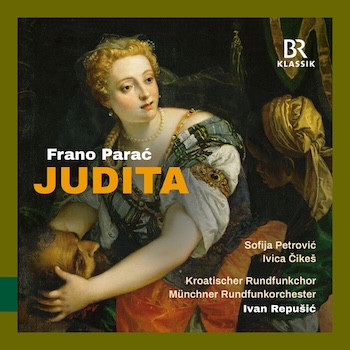

FRANO PARAĆ: Judita, and Dance of the Baroness

Sofija Petrović, soprano; Stjepan Franetović, tenor; Matteo Ivan Rasić, tenor; Ivica Čikeš, baritone; Matija Meić, baritone; Sava Vemić, bass.

Croatian Radiotelevision Choir, Munich Radio Orchestra, cond. Ivan Repusić.

BR 900357—70 minutes.

Click here to try any track or to order.

A new, shortish opera that speaks an immediately accessible musical language is always to be hailed. The latest to come my way is Judita, by the prominent Croatian composer Frano Parać. The work, first staged in 2000 in the important Croatian city of Split (in the Dalmatia region), has been staged repeatedly in that country, and, in late 2024, got a series of unstaged performances in Munich, thanks to the efforts of the Croatian-born music director of the Munich Radio Orchestra, Ivan Repusić.

A new, shortish opera that speaks an immediately accessible musical language is always to be hailed. The latest to come my way is Judita, by the prominent Croatian composer Frano Parać. The work, first staged in 2000 in the important Croatian city of Split (in the Dalmatia region), has been staged repeatedly in that country, and, in late 2024, got a series of unstaged performances in Munich, thanks to the efforts of the Croatian-born music director of the Munich Radio Orchestra, Ivan Repusić.

I did a little research on Croatia, realizing that I knew too little about this country, which has close to four million inhabitants. Croatia, for decades, was part of Yugoslavia. It became an independent nation-state when Yugoslavia (long held together by Marshal Tito) broke up in the years 1989-91. Croatia’s important cities include Zagreb, Split, and (on the Adriatic coast) Dubrovnik. It is separated from Austria by Slovenia (another state that was part of former Yugoslavia), and its Adriatic coastline merges northward into that of Slovenia (briefly) and then of Italy.

Not surprisingly for a country in southern and eastern Europe, Croatia has a rich tradition of music making, including Antonio Janigro’s famous I Solisti di Zagreb, the light-opera composer Franz von Suppé (born in Split—his father was an Austrian civil servant, at a time when Dalmatia was a Habsburg crown land), the modernist composer Milko Kelemen (who studied with Messiaen), the renowned operatic soprano Zinka Milanov, and the world-renowned cellist and singer who goes by his family name, in upper-case: HAUSER (his first name is Stjepan).

Two Croatian operas have long held the stage in Croatia and nearby countries (sometimes translated into the local language, e.g., into German for performances in Vienna): Ivan Zajc’s 1876 grand historical epic Nikola Šubić Zrinjski. and Jakov Gotovac’s 1935 comical village tale Ero the Joker (Ero s onoga svijeta). I expressed my delight with excellent new recordings of both (click on the links in the preceding sentence).

Well, now we have a much more recent Croatian opera to bring delight and variety to the operatic world. Parać’s Judita (2000) is neither historical nor comic but, rather, biblical, as is perhaps appropriate for a country whose population is, from what I have read, some 80% Catholic, plus a small number of Serbian Orthodox believers (though growing numbers of people, as in many other countries, consider themselves non-religious).

Judita retells the basic storyline from the Book of Judith, to which the libretto-writing team (including the composer) has added some secondary characters to flesh out the action. Much of the wording comes from a famous 1501 poetic rendering by Marko Marulić, which is renowned for being one of the earliest substantial works of Croatian literature. (To be accurate, the Book of Judith is excluded from the Jewish scriptures and considered part of the Apocrypha by Protestants, but it is indeed included in Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Bibles.)

This seems to be the work’s first commercial audio recording. A full video is available on YouTube (alas without subtitles), as are selected scenes and interviews. The videos derive from various performances in Split, beginning with the work’s world premiere in 2000. A 2005 DVD of the opera, on the Cantus label, seems hard to procure from North America. Details are at discogs.com.

The main characters of Parać’s opera are Judith (Judita: soprano or mezzo-soprano) and Holofernes (Oloferne: baritone), Judith’s maid Abra (soprano), the Judaean high priest Eliakim (bass-baritone) and the prominent Judaean elder Akior (or Achior, tenor). I am preferring here to call the Bethulians Judaeans, though the booklet calls them “Jews,” a term that, to my ear, suggests a much later period in history. (“Israelites” might be another option.) The whole question of where Bethulia was located is much disputed by scholars and religious authorities, some identifying it with Jerusalem and some with a town in Samaria (to the north); others consider it wholly legendary.

The story tells of Judith’s attempts at quelling the despair of the Judaeans, whose city is being besieged by Assyrian troops, under the leadership of Holofernes. In Act 2 (consisting of scenes 5-7) we meet the obnoxious Assyrians, and Judith urges the Bethulians not to surrender. She then goes into action: seducing Holofernes, getting him drunk, cutting off his head, and returning home with the head in triumph.

The splendid Judith in this recording: Sofija Petrović. Photo: TACT

Dozens of other musical works derive in some way from the Book of Judith, including by Thomas Tallis, Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre, Vivaldi, Mozart, Hubert Parry, and Arthur Honegger. The booklet-essay explains that, for Marulić and for generations of Croatian readers thereafter, the Judaeans were (and are) understood as symbolic of the Croatians. The nasty Assyrians thus stood (and stand) for the Ottoman Turkish army, which repeatedly tried to conquer Croatian lands, even made it to the gates of Split a century after Marulić (in 1699) but was definitively repelled.

The videos on YouTube repeatedly show the city of Bethulia nestled under a cross that is illuminated by a spotlight, thus emphasizing that the inhabitants are to be understood as proto-Christians. This interpretation is consistent with longstanding Christian hermeneutic traditions. A parallel can be found in Handel’s dramatic oratorios: the Israelites and Judaeans in them were clearly understood at the time as representing England’s Protestant rulers (God’s chosen ones), and the Egyptians, Philistines, and other of ancient Israel’s foreign foes represented Catholicism, which is to say the Stuarts, France, Spain, and Rome.

Parać’s opera is laid out in very traditional manner: the choral movements alternate with arias and duets. There are very effective numbers involving interchanges between solo and chorus, as in the opening scene: after a touching chorus in which the inhabitants of Bethulia bewail the siege on their city, Akior (the captured vizier of the Assyrians) reveals to the Judaeans the evil deeds of Holofernes, and the high priest Eliakim and the respected Judaean elder Ozija order the citizens to block the gates and to defend the city with “Weapons, arrows, and bows” (words repeated many times, aiding comprehension).

Judith gets two big arias—one in each of the two short acts—that are so effective that I can imagine one or the other getting included on aria albums (but you’d need a chorus as well). Particularly engaging is the aria that ends scene 4 (and act 1): “Make him desist from evil. Take away his sight! Let him be ensnared by my beauty and my eyes.”

There is also a quite wonderful dance number for the brutish soldiers of Holofernes in Scene 6, though it is cut off dramatically, rendering it unsuitable for being performed on its own as a concert number (unlike the “Bacchanale” from Samson et Dalila or “Dance of the Seven Veils” from Salome).

Judita contains substantial passages for chorus, which surely make it apt for unstaged performance. (Some of these passages are reportedly based in part on Croatian sacred music, a fact that I must take on . . . faith.) In this sense, the work resembles Handel’s aforementioned dramatic oratorios (say, Judas Maccabaeus or Jephtha) or certain heavily choral operas that, though originally intended for performance with sets, costumes, and on-stage movement, work well in the concert hall. I’m thinking of Samson et Dalila: a work that likewise features a central female temptress (though in that case things are reversed: she is the evil foreigner, and the warrior Samson represents God’s chosen people).

Croatian composer Frano Parać. Photo: ArtCaffe

Frano Parać will be new to many. I have read that he started out as a rock musician, then went on to get training in Zagreb and then at Milan’s Radio Italiana studio for electronic music. He eventually became professor at the same Zagreb conservatory where he had once studied; there he, among other things, headed, for a time, the electronic-music studio.

Despite Parać’s involvement in electronic music, I find nothing high-modernist about Judita. Its style, well rooted in triadic harmony, is immediately accessible, reminding me at times of Carl Orff or, say, Gottfried von Einem. (I loved a recording of von Einem’s opera Der Besuch der alten Dame, based on the famous Dürrenmatt play known in English as The Visit.) The scenes are well-shaped, often building to a satisfying climax. The vocal lines seem well crafted—singable without becoming predictable. Indeed, they come across well in the various videos on YouTube: even though the singers on those videos are mostly different than the ones heard here, they are clearly just as well trained and stage-savvy.

The booklet essay claims to find “minimalist” aspects in the work’s use of frequent repetition of short phrases and motives, but this seems a forced comparison: motivic repetition and variation here seem more like what has been typical in concert and theater music for several centuries, including in the works of, to restrict myself to two opera composers, Massenet or Puccini. This is particularly clear in passages of choral yearning, where the repeated phrases rise as a plea to God for deliverance. One particularly effective instance is when, in Scene 3, the starving Bethulians pray for release from the Assyrian siege.

The recording, compiled from unstaged performances in Munich’s renowned Prinzregententheater in late 2024, is well engineered and vividly conveys the stage atmosphere. I was particularly taken with the singing of Sofija Petrović, as Judith: she can caress seductively or cry out like a heroic trumpet, always securely on pitch and without a wobble. Indeed, all the singers (most of whom are native Croatians) have solid yet flexible voices and put the text across convincingly. I look forward to hearing them in other repertoire as well, including more Croatian works!

A scene from the 2024 production of Parać’s Judita staged at the Croatian National Theatre, Zagreb. Photo: OperaVision

The recording comes with high praise from the music critic Ingobert Waltenberger (in German), and I am happy to echo his words here: “Repusić’s full-blooded interpretation, though it took place in a ‘mere’ concert performance, conveys a passionate stage atmosphere. Wunderbar!” The work is so concise that the CD can end with an additional short item by Parać: the lively and attractive three-minute “Dance of the Baroness” from his 1980 ballet based on texts by Miroslav Krleza (whose writings are described in the booklet as “expressionist-modernist”).

All of this made me want to hear more works by this composer, so esteemed in his native land and so little known abroad. Fortunately, I was able to find a few on Spotify (for chamber ensemble, for orchestra, and for chorus), and they confirm my impression that this is a composer who knows what he wants to do and puts it across winningly.

The fine booklet (in German and English) includes a detailed synopsis but, alas, no libretto. At my request, a Croatian colleague got a complete English translation from the composer and forwarded it to me. This immensely informative item turns out to be the booklet to the aforementioned Cantus DVD. The translation is in somewhat antiquated English, to reflect Marulić’s centuries-old Croatian.

But what are regular opera lovers to do who don’t have friends in Croatia? Couldn’t the libretto be put online, even belatedly? If this happens, I’ll be happy to spread the word, so that more listeners can appreciate this fascinating and stirring newish opera—which clearly deserves to be performed in many lands. Perhaps a singing translation could be created in some more familiar language—such as English, French, German, or Italian—so an international cast of singers can convey the words meaningfully instead of trying to pronounce Croatian to a non-Croatian audience (who would have to be looking up at supertitles the whole time).

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music and Senior Editor of the Eastman Studies in Music book series (University of Rochester Press), which has published over 200 titles over the past thirty years. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, The Boston Musical Intelligencer, and Classical Voice North America (the journal of the Music Critics Association of North America). His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and is included here, lightly revised and updated, by kind permission.

Tagged: "Judith", Croatian Radiotelevision Choir, Frano Parać