Jazz Album Review: “American Crow” — Maria Schneider’s Urgent Jazz EP Crows Against Big Tech

By Allen Michie

Composer and bandleader Maria Schneider is a storyteller, and that’s the best way to approach her music for the first time. You listen like you read a short story, with your full attention, and your imagination synced with all of your senses.

American Crow, Maria Schneider Orchestra (ArtistShare)

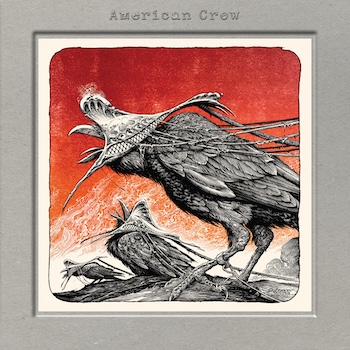

Usually when you see the word “Ornithology” on the back of a CD cover, you assume it’s going to be a cover of Charlie “Bird” Parker’s famous composition. In this case, the word is used in a credit to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology for their 2019 field recording of crows encountering a Cooper’s Hawk. Maria Schneider, long an avid birdwatcher and a kind of avian musical philosopher, has expanded her orchestra on one track to include dramatic crow caws. Fantastically hooded crows also appear on the strange and ferocious CD cover.

There’s no Charlie Parker here. Schneider has invented her own kind of jazz, and it’s set a new paradigm for what is being done in contemporary big bands today. “Big band” is a technically accurate description, but Schneider has long since absorbed the classic big band tradition, having trained with the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis big band and Gil Evans, and then moved far beyond it to find her own immediately distinctive voice with her Orchestra. For all of her influence on contemporary jazz, she’s doing something completely original — no band sounds quite like this one. Just a few seconds of accordion paired with flutes and rumbling low bass, and you know you’re hearing the Maria Schneider Orchestra.

Schneider’s latest, American Crow, is an anomaly in her catalog. First, it’s an EP, with three tracks clocking at a total of 30:02. Second, two of the three tracks are different takes of the same song (and you can hardly blame her, because it would be criminal not to release both versions of Mike Rodriguez’s moving trumpet solos), one of them adding the sound of real crows. Third, this is a follow-up of sorts to a previous album (in this case, Data Lords, although perhaps there’s a precedent in “The Sun Waited for Me” on Data Lords being a setting for a Ted Kooser poem, which was a concept for a previous album, Winter Morning Walks). Fourth, the alien but organic cover art is harsh, and the rough-stitched undyed cardboard CD jacket is a 180-degree turn from the elaborate and sophisticated packaging of her previous discs (especially the pastoral The Thompson Fields, which was a beautiful little hardback book). None of these are complaints. My point is that Schneider is stretching, and like with Miles Davis before her, we all get to listen while she tries out what else she can do.

The personnel has shifted, as they do—and should—in big bands. Not since Duke Ellington has a composer and bandleader enjoyed such an extended period with voices she intuitively knows and trusts. American Crow has Rich Perry, Tony Kadleck, Greg Gisbert, George Flynn, and Jay Anderson, who were all there for her first album, Evanescence, 32 years ago. A few of her featured soloists from the recent past aren’t here. Pianist Frank Kimbrough and trumpeter Laurie Frink have passed away. Saxophonist Donny McCaslin and guitarist Ben Monder, both much busier since blowing up their profiles by playing brilliantly on David Bowie’s Blackstar, are missing. Ingrid Jensen’s solos brought chills on Sky Blue. Master accordionist Gary Versace has taken over for Kimbrough on the piano bench. They are all missed, but their replacements are superlative. I expect pretty much every jazz musician on the planet would pick up the phone if Maria Schneider called, and she knows precisely what voices she needs.

The instrumentation and their combinations follow no rules except what she’s hearing, moment by moment, and the structures of her all-original compositions and arrangements create their own internal narrative logic. She’s a storyteller, and that’s the best way to approach her music for the first time. You listen like you read a short story, with your full attention, and your imagination synced with all of your senses.

The story on American Crow is, like disc one of Data Lords, about the corrupting influence of Big Tech on our ability to form connections with one another and nature. It’s an indictment of all the narcissistic little devices that keep us looking down rather than up, paying more attention to (what used to be called) Tweets rather than bird songs, symptomatic of our declining capacity for simply listening to one another. As Schneider says in one of the accompanying online video interviews, this project is about a “crisis of listening,” all of us “being fed with what we already think, then we get siloed.”

The story begins with a fanfare. On the first take of “American Crow,” the trumpets mimic crows’ calls with mutes. The full orchestra gradually pares down to just one trumpet, and Mike Rodriguez’s compelling solo starts. It’s his “star is born” moment—he has earned a long, relaxed, exploratory solo, introspective yet fully grounded in the kaleidoscopic textures and harmonies of the complex composition. His tone and phrasing are sometimes a bit like Ingrid Jensen’s, and he tends to stay in the middle range of the horn with a full sound, minimal vibrato, and no gimmicks. It’s just melodic invention and honesty. It’s a solo that pulls you in to listen.

Grammy-winning composer, bandleader, and NEA Jazz Master Maria Schneider. Photo: Briene Lermitte

Schneider keeps the accompaniment shifting. I have no idea how, but she manages to make it sound like there are harmonizing human voices. It’s worth listening to the piece multiple times in order to zero in selected musicians: for starters, Johnathan Blake’s expressive drums, how so many different instruments change character when blended with Julien Labro’s accordion and, of course, Schneider’s signature voicings in the low end, grounded powerfully by Scott Robinson on contrabass clarinet and George Flynn on contrabass and bass trombone. Sometimes the accompaniment is simply led by Versace’s gentle touch on piano.

At one point in “American Crow” the sky grows very dark, with the trumpets stabbing in sharp triplets, like crows fighting over a piece of roadkill. The low brass grumbles ominously in a minor key. More trumpets join the soloist, and the single crow turns into a flock. I’ve witnessed the entire sky turn to night as hundreds of crows lifts off a field in Iowa, and I can tell Schneider must have also seen something like this in her native Minnesota.

As Rodriguez continues his solo in the same steady vein, a faint contrasting light on the horizon begins to grow. There’s a chattering of horns from across the orchestra, like a murder of crows communicating their next move. Or perhaps it’s a cacophony of American chatter online, simultaneous chaotic blather, everyone talking and no one listening. Or perhaps it’s both.

Then it abruptly ends. There’s no resolution. Rodriguez, like a prophet, continues to speak his truth, and he has the last word.

“A World Lost” is a new arrangement of a piece that appeared on Data Lords. This time it’s a feature for Jeff Miles, taking over from Ben Monder on guitar. This arrangement cuts the second solo, which was taken by Rich Perry on tenor sax on Data Lords, and Miles has the entire song to himself. Schneider adds some accordion, opens it up more, and makes it sound somehow airier.

Miles plays with many more textures than Monder did on his more brooding solo. I hear traces of Bill Frisell, John Scofield, and Jimi Hendrix as it goes. He’s his own player, however, and he’s full control of various voices and approaches to phrasing throughout his long solo. As any soloist with this orchestra must do, he’s keenly attuned to the landscape shifting under his feet.

As the piece develops, there’s an odd syncopation in the low brass accompaniment that keeps things slightly off kilter. The solo grows knotty and harmonically complex over the scorched-earth sound, then it lifts when the time is right. Miles lays it on with the pedals and technology toward the end of the solo, which pares itself away to single notes and surrenders to the folksy accordion, like the first trace of sunrise after a cloudy night.

Please do watch the artistic video of “American Crow” on YouTube. Schneider made an exception to her career-long ban of her recordings on the abusive streaming services because she felt so strongly about her message reaching the broad public. “It speaks to the toxicity of our present social discourse that’s devolved into an impenetrable knot of curated rage,” she writes in the video notes. “We crow about each other incessantly, having lost almost any ability or wish to really listen and understand those with whom we disagree. . . . A true jazz improvisor thrives on listening: waiting, responding, considering, reconsidering, responding again, sometimes in ways that surprise even the improvisor. Jazz is at its best when everyone is vulnerable. Improvisation asks everyone to risk what they think they know, and offers them an opportunity – through listening – to discover something new in themselves. Jazz shines a light on what we are allowing to slip away in our brittle and fractured world, making our art form more relevant today than ever before.”

Those who purchase a copy from ArtistShare get access to a series of interviews and videos of the recording session. There’s a moment in one of the videos where she’s demonstrating on the piano how she built “American Crow”: “Motivic development. Like Beethoven.” Then she modestly laughs, and says “Well, not Beethoven.”

I didn’t laugh. The comparison is valid.

Allen Michie works in higher education administration in Austin, Texas. His previous overview of Maria Schneider’s career, and a review of Data Lords, can be found on the Arts Fuse here.