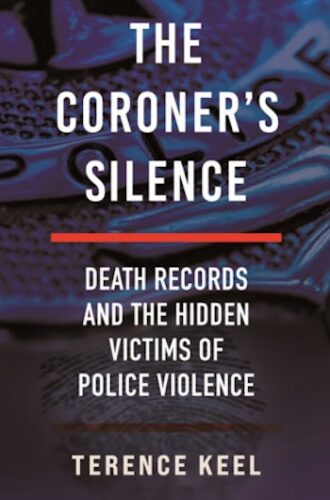

Book Review: “The Coroner’s Silence” — A Chilling Inquiry into Institutional Indifference

By Bill Littlefield

The title of this revelatory book might suggest that it’s limited to uncovering the deficiencies and biases of a particular profession. But The Coroner’s Silence is far more than that.

The Coroner’s Silence: Death Records and the Hidden Victims of Police Violence by Terence Keel. Beacon Press, 212 pages,

The fourth chapter of The Coroner’s Silence is titled “Collecting Fragments.” These “fragments” add up to a powerfully concise assertion: “Dying in custody is the new capital punishment.” That sentence is preceded by a reference to “a death ledger” that’s been assembled by the author and his research colleagues. According to their findings, “between 2000 and 2020, police killed 32,104 people during arrest.” Of course, “during arrest” does not account for all the people who have died in various jails and prisons, some by their own hand, some after beatings by correctional officers. Sketchy reporting practices complicate compiling an accurate number of those deaths.

The fourth chapter of The Coroner’s Silence is titled “Collecting Fragments.” These “fragments” add up to a powerfully concise assertion: “Dying in custody is the new capital punishment.” That sentence is preceded by a reference to “a death ledger” that’s been assembled by the author and his research colleagues. According to their findings, “between 2000 and 2020, police killed 32,104 people during arrest.” Of course, “during arrest” does not account for all the people who have died in various jails and prisons, some by their own hand, some after beatings by correctional officers. Sketchy reporting practices complicate compiling an accurate number of those deaths.

32,104 is only one of the thoroughly alarming statistics presented by Professor Terence Keel, who teaches human biology, society, and African American studies at U.C.L.A. He is also the founding director of the BioCritical Studies Lab there, and the author of several previous books.

As the title suggests, The Coroner’s Silence is intended, in part, to expose how often the examinations of cases involving victims of violence — perpetrated by the police, correctional officials, and others charged with capturing or containing citizens — end up exonerating the people in charge. Based on the evidence, Keel convincingly asserts that “it is terrifying to witness a criminal justice system that can take someone’s life, a system in which safeguards designed to tell us what happened covers up the truth, redacts files, and stonewalls families, reporters, or anyone searching for answers.” He backs up this assertion through a close scrutiny of case studies, some of which he was able to uncover only through tenacious investigation.

Professor Terence Keel. Photo: courtesy of the artist

The Coroner’s Silence also provides a history of the development of the offices of coroner and medical examiner over the past two centuries. Over time, he charges, the men and women given the responsibilities of those offices have become more and more inclined to downplay, ignore, and cover up cases where police officers or corrections officers have been responsible for the deaths of people in their custody. He associates that corruption with the more general “processes of neglect and indifference that have been steady features of American life.” The injustices and cruelties that Keel chronicles in this book don’t exist in a vacuum. They are evident in the indifference of a country that’s willing to shrug off the fact that an enormous number of people not only fall below the poverty line, but that they “have grown used to living in the absence of care.” People “mistake neglect for preexisting health conditions, mental illness, problems with substance abuse – as if those [who are] suffering were free to simply manifest better bodies or make different decisions.”

Keel argues that America is failing to recognize the dangers that follow when “a nation [is] not fully committed to the well-being of the public,” a situation that inevitably creates “unhealthy people.” When family members or neighbors feel they cannot help those “unhealthy people” and call the police for assistance out of desperation, too often the “unhealthy people” suffer damage and even death at the hands of the police. That truth is often ignored or covered up by the very officials charged with discovering the mistreatment and seeing that it is revealed.

Keel’s promise in The Coroner’s Silence is “to show what it looks like when medical examiners neglect social, legal, and political realities that shape who perishes in custody.” He also posits some alternatives to a system that too often victimizes people who’ve already suffered from the harm caused by repressive “social, legal, and political realities.” For example, Keel writes about communities that have organized resources that provide desperate folks with an alternative to calling the police. In these places, people are given the means to summon social workers, mental health professionals, and others trained to deal with the sorts of crises that police officers too often approach with guns drawn or mace and tear gas at the ready.

The title of Keel’s revelatory book might suggest that it’s limited to uncovering the deficiencies and biases of a particular profession. But The Coroner’s Silence is far more than that. In his final chapter, “The Bodies That We Don’t See,” the author delivers a well-earned generalization: “Our politics reflect the belief that people on the wrong side of the law are not like us.” He goes on to insist that “not enough of us believe that criminals can be helped with institutions that offer care, shelter, and dignity,” and that “justice is more than a bureaucratic process.” True justice “requires us to return to our humanity.” It’s hard to imagine a more necessary or timely message given an administration that’s so thoroughly dedicated to preaching hatred and revenge. Genuine justice hardly seems to stand a chance.

Bill Littlefield volunteers with the Emerson Prison Initiative. His most recent novel is Mercy (Black Rose Writing)