Jazz Album Review: Sun Ra and His Arkestra Live at The Left Bank — Cosmic Swing and Ragged Glory

By Michael Ullman

Sun Ra was often deliberately far out, as we used to say, and also joyously entertaining.

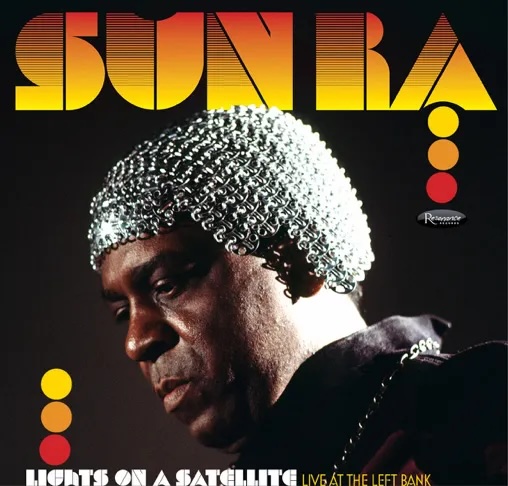

Sun Ra, Lights on a Satellite: Live at the Left Bank Resonance, (2 LPs)

“You are not Earth people,” I heard the avant-garde bandleader and amateur Egyptologist Sun Ra chant at an Ann Arbor jazz festival, “you are space people.” Earth people pollute, practice racism, and don’t go to hear Sun Ra’s Arkestra. We had passed a test just by being there. Sun Ra was often deliberately far out, as we used to say, and also joyously entertaining. His band dressed in futuristic costumes: Ra himself often had a crown as well as a glittery cape. When he could, he featured dancers and singers, including June Tyson, who did both. His band members were fiercely loyal: his steady saxophonists included Marshall Allen and Pat Patrick, who were with him, with some breaks, for decades. His music was more varied, and sometimes, more conservative, than one might guess. He played boogie-woogie piano, remade swing era hits, and dabbled in the bebop repertoire. Nor was he afraid of Ellingtonian lyricism.

“You are not Earth people,” I heard the avant-garde bandleader and amateur Egyptologist Sun Ra chant at an Ann Arbor jazz festival, “you are space people.” Earth people pollute, practice racism, and don’t go to hear Sun Ra’s Arkestra. We had passed a test just by being there. Sun Ra was often deliberately far out, as we used to say, and also joyously entertaining. His band dressed in futuristic costumes: Ra himself often had a crown as well as a glittery cape. When he could, he featured dancers and singers, including June Tyson, who did both. His band members were fiercely loyal: his steady saxophonists included Marshall Allen and Pat Patrick, who were with him, with some breaks, for decades. His music was more varied, and sometimes, more conservative, than one might guess. He played boogie-woogie piano, remade swing era hits, and dabbled in the bebop repertoire. Nor was he afraid of Ellingtonian lyricism.

I talked to him once, in New York after he finished a solo piano recital. I told him that on my first night in Ann Arbor as a graduate student in the fall of 1968, I was wandering around the town despairingly. Everything was quiet at 9 p.m. I had just come from Chicago, where things would just begin popping at that hour. I wondered what I had gotten myself into. Then I passed a little concrete building and heard some music. I opened the door and there in all its performative glory was the Sun Ra Arkestra. I told him he saved me that night, and he nodded as if to reply, “Of course I did.”

Sun Ra at the 1972 Ann Arbor Jazz Festival. Photo: Michael Ullman

He was, he liked to say, from Saturn, or had a Saturnian experience, and also from Birmingham, Alabama, which he called the Magic City. Though he sometimes obscured the date, he was born in 1914, which meant that he had come of age during the height of the swing era. He was especially influenced by the big band of Fletcher Henderson, whose two hits, “Yeah Man” and “Big John Special,” are recreated on Lights on a Satellite, which was recorded on July 13, 1978.

At that moment, the band was riding high: on the previous May 20, the Arkestra had appeared on Saturday Night Live. That must have been a treat. It was always better to see Sun Ra live, for his majestic pacing around the stage, for the occasional theatrics of the band, the dancing and prancing, and the costumes. The band didn’t just appear: they promenaded. The last full number of his set on Lights is the bouncy, repetitive chant, “We Travel the Spaceways,” which Sun Ra used to escort the band off the stage. It was fun to watch. Here on record we only hear the band fade away, but we can get the idea. Being that the composer was from Saturn, many of his pieces on Satellite are space travel–oriented, but he also throws in versions of “Cocktails for Two” (he was a nondrinker), Tadd Dameron’s “Lady Bird,” and Judy Garland’s hit “Somewhere Over the Rainbow.” He has room for varied textures: he is leading an approximately 18-person band. (I am not sure how to count the Jingle Brothers.)

It all begins with a “Thunder of Drums.” After the percussion section, Sun Ra enters on an electric piano set up to sound like an organ. He is playing no recognizable melody: this is free, and I would say deliberately eccentric sounding music. He solos, using the instrument to create strange glissandi, phrases that sag in pitch like a balloon with a hole in it, as well as sudden swirls and grumbles. Then vocalist June Tyson enters, singing of receiving vibrations from an asteroid. She asserts, “The spaceways are not so far/ the vibrations are in your heart.” It’s a good-time message, democratic and joyous: open yourself up to the vibrations and “Your world becomes a star no matter who you are.” Subsequently, Sun Ra plays a solo piano version of “Over the Rainbow.” Some members of the audience giggle, but I think he is serious. He plays a two-handed style of piano, which allows him to jump about irregularly dissonant chords, sometimes accenting with the finesse of a pile driver. Ra plays the difficult bridge frantically — only to come to a thumping stop. From then it is a fraught battle between the innocent melody and the pounding piano. It ends sweetly.

Sun Ra and band at the 1972 Ann Arbor Jazz Festival. Photo: Michael Ullman

Ra likes the word “pleasant.” Here it’s in the name of his next piece, “A Pleasant Place in Space.” Elsewhere, his lyrics assert “They say you are a pleasant sort.” This is a high compliment in Sun Ra’s world. His “Space Travellin’ Blues” turns out to be a version of “St. Louis Blues.” It has some band-riffing by the horns, and a guitar solo, but here again Ra himself is featured rather than the band. The Arkestra then is given the opportunity to show off in an impossibly fast version of the Fletcher Henderson piece “Yeah Man,” based on “Rhythm” changes. The first solo is by John Gilmore on clarinet. Marshall Allen is then heard on alto. It’s a wild ride, far from the elegance of the Henderson recording.

“Lights on a Satellite,” the title piece, is by contrast gentle in sound and intention. The band plays a sweet riff behind the saxophone soloist, though Marshall Allen’s piccolo comes off as a little disruptive. (Piccolos are always disruptive.) The Arkestra performs another unexpected standard, “Cocktails for Two.” In the glissandi of the alto solo, I hear references to Ellington’s Johnny Hodges. Ra rumbles frantically through his uptempo solo on “Half Nelson.” Here the whole band pushes the soloist into what at times builds into a joyous cacophony. Ra brings back the theme. There’s nothing neat about these performances: I wonder what Henderson would have thought of them. Ragged through and through, this varied set is nonetheless a vigorous delight that we can now share with an obviously ecstatic audience who was lucky enough to have been at the Left Bank. Put on a cape and check it out.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 30 years, he has written a bimonthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. He is emeritus at Tufts University where he taught mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department.

Tagged: "Lights on a Satellite: Live at the Left Bank", Resonance, Sun Ra