Book Review: The Insider’s Legacy: Malcolm Cowley and the Rise of U.S. Literature

By Thomas Filbin

Literary critic Malcolm Cowley’s in-the-trenches vision of modernism deserves to extend beyond the halcyon epoch he witnessed — a case made splendidly by Gerald Howard’s biography.

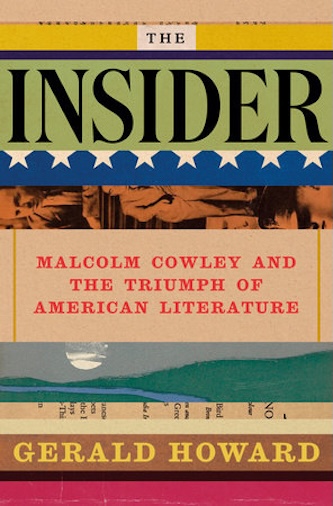

The Insider: Malcolm Cowley and the Triumph of American Literature by Gerald Howard. Penguin Press. 534 pp. $35

Paris in the 1920s was filled with many wide-eyed Americans just done with service in World War One and now experiencing the old world. They discovered art, amazement, seduction, and for writers, a demand for novelty. The dollar spent well against the war-torn franc and young men seeing half-naked women dancing on stage without being arrested was a shock. Malcolm Cowley, a young man from Pennsylvania whose brains got him into Harvard University and whose curiosity and congeniality made him friends, was part of this world, and its spell lingered over the course of his long and storied life in letters as an editor and critic.

Paris in the 1920s was filled with many wide-eyed Americans just done with service in World War One and now experiencing the old world. They discovered art, amazement, seduction, and for writers, a demand for novelty. The dollar spent well against the war-torn franc and young men seeing half-naked women dancing on stage without being arrested was a shock. Malcolm Cowley, a young man from Pennsylvania whose brains got him into Harvard University and whose curiosity and congeniality made him friends, was part of this world, and its spell lingered over the course of his long and storied life in letters as an editor and critic.

An editor for many years, Gerald Howard has penned a compelling biography of Cowley that not only chronicles its subject’s long life (1898-1989) engaged in literature, politics, and world. He does not lose Cowley in a sea of facts, but has honed a shapely narrative, one whose vim and vigor springs from his editorial smarts — he knows what information to use and what to leave out.

Cowley was born to middle-class parents in Pennsylvania and excelled at school. Still, arriving at Harvard was a jolt. Many of his classmates were “St. Grottlesex” boys of privilege. Cowley plainly felt second class among them. He had brains and energy, however, and excelled. When World War One broke out — though before America formally entered the conflict — he joined others, such as Ernest Hemingway and John Dos Passos, to serve as volunteer ambulance drivers and medics. The American Field Service served as a kind of school, where the young men would learn about France and in the process discover things about themselves. The work was intermittent, and Cowley took advantage of the free time to read Rimbaud, Verlaine, Baudelaire, Dostoyevsky, and Huysmans. This immersion into modernist views of life and letters changed his perspective.

Returning from the war, Cowley re-entered Harvard, but annoyed his parents (he was an only child) by marrying an older woman without their approval. They cut off his financial support, and Cowley had to find his own way to fund the rest of his time in Cambridge. Not much is mentioned about his parents by Howard after this; the inference is that they effectively disowned him. Cowley graduated in February, 1920 and moved to New York to do freelance writing. Malcolm and his wife Peggy lived hand to mouth in a fifth floor flat overlooking the Sixth Avenue El. The spirit of the new called, however, and they left for Paris in July of 1921.

The post war environment was a carnival world of war-weary young men looking to find their new lives. Economically it was a time of anguish for many in Europe (particularly in Germany), but it was the best of times for Parisian bohemians. Hemingway, James Joyce, E.E. Cummings, and Dos Passos were participants in a creative hothouse. Books, alcohol, arguments, and work made every day tumultuous — a fertile communal struggle.

Because the country’s entry into the war had tipped the balance, Americans in Paris were treated with admiration. The low cost of living and an increase in freelance opportunities gave Cowley the time and space to develop his own ideas, which could run counter to the accepted avant-garde line. Howard writes:

Many people have assumed that, given Cowley’s close association with the figures of the Lost Generation and some of the antics he would get up to in Paris, he was a prime specimen of the flaming literary youth of the twenties. In fact, his consistent admiration for traditional literary forms and the practice of writing as an honest craft…ran counter to the ideas that governed the literary avant-garde in the early years of the Modernist explosion.

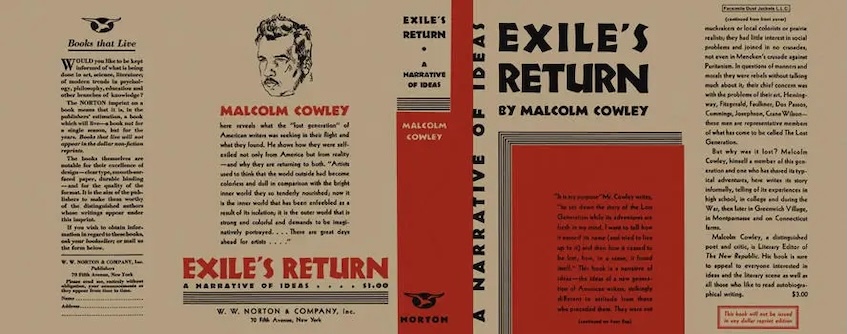

Cowley remained in Paris and wrote essays and profile pieces of writers. Although he differed from the crowd, he served as a kind of shepherd for the movement, watching over the flock of free spirits. Exile’s Return, published in 1934 (rev. 1951), remains the best chronicle of those crazy, productive, and original years. It was a literary renaissance, and Howard argues that Exile’s Return defined that generation’s experience of that savage war as a watershed experience, an inspiration for an ongoing process of cultural deracination. Cowley helped forge the indelible image of Hemingway writing in pencil while nursing a drink or coffee in the Rotonde or the Dome .

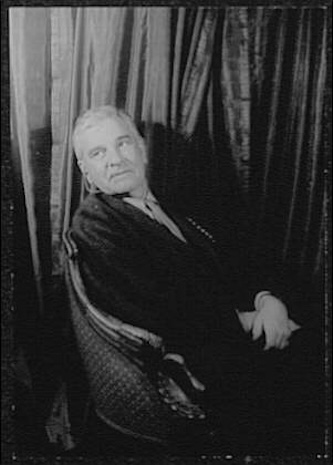

Malcolm Cowley, photographed by Carl Van Vechten, 1963. Photo: WikiMedia

When Cowley returned to America, he found that a culture war was raging. Greenwich Village was the epicenter of the new thinking: “freedom of thought and expression, unfettered sexual behavior, gender equality, abandonment of middle-class notions of guilt and shame, and the virtue of constantly moving on.”

Cowley dived into the melee. He that found his métier and calling was to be at the epicenter of culture. Cowley wrote voluminously and constantly for “little’ magazines. Long hours and low pay were inevitable, but Cowley had the energy and desire to plug away regardless of the scant rewards for ink-stained wretches. Howard writes, “Malcolm Cowley lived an orderly life, hardly bourgeois, but he met deadlines and wrote to editorial order and always had a fixed address and a few dollars in the bank.” 1929’s Blue Juniata, a book of poems, proved him more than a critic and observer, but a creative force as well. Of course, he had always been creative. Criticism is often maligned as hack work, but incisive interpretation and judgment offers as much possibility for literary originality as do novels, poems, and plays.

Cowley’s marriage did not last after Peggy had an affair with Hart Crane. He was later happily remarried to Muriel Maurer, a fashion writer and editor, and they had a son. The ’30s were a turbulent period — economically, socially, politically — and Cowley was as engaged with left-wing politics as well as literature. He was hired by The New Republic in the ’30s, and his political views veered leftward, a direction that would entangle him in ideological red tape and battles that he would later regret. Accused of being a communist sympathizer — because of his associations with leftist organizations — he quit a wartime government job in Washington after being hounded by right wing journalists such as Whittaker Chambers and Westbrook Pegler. Literature was his true calling though, and he edited several Viking books such as The Portable Hemingway (1941) and The Portable Faulkner (1946), the latter playing a pivotal role in reviving the Southern writer’s flagging reputation.

Cowley continued his critical career, often lecturing at universities and teaching creative writing classes. He became the grand old man of American letters; he lived past his 90th birthday, dying in 1989. He has enjoyed a long and productive life, eyewitness and midwife to so much of twentieth century literature. Modernity caught up with him, however; he was befuddled as the ’70s veered further into satire, farce, and magical realism. If the Cowley of the ’20s is what stands in the historical spotlight, that is no small epitaph. In the 1951 edition of Exile’s Return, Cowley added a postscript:

I haven’t told you about the good winter when my friends used to meet two or three times a week at John Squarcialupi’s restaurant. We were all writing poems then, sitting after dinner around the long table in the back room we used to read them without self-consciousness, knowing that nobody there would either be bored by them or gush over them ignorantly. We were all about twenty-six, a good age, and looked no older; we were interested only in writing and in keeping alive what we wrote, and we had the feeling of being invulnerable – we didn’t see how anything in the world could ever touch us, certainly not the crazy desire to earn and spend more money and be pointed out as prominent people.

But that was the ’20s — and time and tastes march on. Howard supplies a poignant observation about the sea change in American letters, when literary criticism left the journalism that had sustained Cowley and took up stultifying residence in the university: “The New Criticism privileged the literary qualities of irony and ambiguity and was ever in search of symbols and mythic patterns in texts.” Rebutting this trend, and in spirit of Cowley, he cites a quote from Gore Vidal about the scholar-squirrels of academe: “They go about dismantling the text with the same rapture that their simpler brothers experience taking apart combustion engines.” Now, with literature marginalized-to-the-max in a screen-crazy, cut-to-the-chase society, the scholar-squirrels are being kicked out of the trees as English classes are eradicated.

Literary wars (or our now reduced skirmishes) will be eternal, no doubt, but some generals and their campaigns make history. Cowley’s in-the-trenches vision of modernism deserves to extend beyond the halcyon epoch he witnessed — a case made splendidly by Howard’s biography.

Thomas Filbin is a freelance critic whose work has appeared in The New York Times Book Review, The Boston Globe, and the Hudson Review.

The author of THE INSIDER — that would be me — very much appreciates this well written and perceptive review. It is good to be understood.