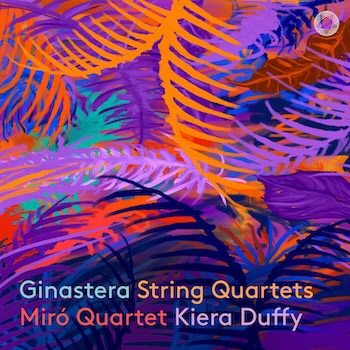

Classical Music Album Review: Miró Quartet Plays Alberto Ginastera’s Three String Quartets

By Jonathan Blumhofer

The album ends up paying dividends, not just for fans and students of 20th-century composition, but for anyone interested in the broader reach and global development of classical music in the last century.

To enter the world of Alberto Ginastera is to visit a place that’s at once very strange and very familiar.

Unlike his near contemporary, Olivier Messiaen, the Buenos Aires native’s voice didn’t emerge seemingly fully formed. Even as one can tease out various influences on his music, however, there’s a singular quality to much of Ginastera’s output that makes his relative neglect all the more inexplicable. The Miró Quartet’s release of the Argentine composer’s three string quartets on Pentatone, then, is just the sort of thing his oeuvre deserves and needs.

The album ends up paying dividends, not just for fans and students of 20th-century composition, but for anyone interested in the broader reach and global development of classical music in the last century. Indeed, this is a project that adds an interesting dimension to contemporary conversations about an art form that is easily (and not necessarily wrongly) accused of gender, racial, and nationalistic narrow-mindedness and bias.

That Ginastera was steeped in a European musical tradition is indisputable. That he adapted that system to express a distinctively Argentinian musical perspective is equally true—and that’s partly what makes the first two installments of this trilogy so captivating.

The Quartet No. 1, which dates from 1948, clearly owes some debts to the model of Bartók: the writing is funky, gritty, rhythmic, sometimes obsessive, and often rhapsodic. It also boasts a nationalistic slant, with nods to gaucho dance forms and traditional Argentine guitar music.

Through it all, the score is intensely expressive and shapely, especially in the slow third movement’s explorations of musical space. At the same time, Ginastera’s command of tension-and-release in this opus—both within movements and across its larger structure—is total (a reminder, among other things, that the man later wrote three operas and six concertos).

The Quartet No. 2 picked up a decade later right where its predecessor left off. This time, though, Ginastera’s musical language was even more uncompromising, employing Serialist procedures.

Even so, the knottier harmonic language hardly gets in the way of the composer’s sense of style and dance. To be sure, there’s a powerful feeling of the quartet tripping—and singing—with purpose. And the tautly motivic organization of materials means that, much as in Beethoven, there’s a clarity to the architecture here that’s decidedly accessible if never exactly easy.

Again, there are feints towards Bartók in the Quartet’s five-movement arch form and various of its textures. But the sheer inventiveness of Ginastera’s ear carries the day, from the otherworldly atmosphere of the central Presto magico to the fourth movement’s impassioned, virtuosic displays and the finale’s ferocious, distortion pedal-like final cadence.

The Quartet No. 3 takes the extremes of the last even further into a landscape the composer described as “a hallucinating climate.” That’s an apt depiction, given the work’s microtonal harmonies, general lack of metric pulses, and willingness to push instrumental techniques and textures to the max. Yet, even as its larger impression is tough and enigmatic, there is touching beauty to be found in Ginastera’s settings of poems by Juan Ramón Jiménez, Federico Garcia Lorca, and Rafael Alberti.

Here, the latter are delivered by soprano Keira Duffy, who demonstrates an outstanding ability to confidently weave in and out of the Miró’s amorphous textures and precisely enunciate the given texts. The instrumentalists navigate the music’s demands—from lush and improvisatory to eerie, reflective, and delicate—with total command.

Their performances of the first two Quartets are just as locked-in: exuberant and kinetic in explosive moments and, at other times, haunting and shadowy. Throughout, the group’s performances are never less than characterful. Throw in excellent, informative liner notes from Miró violist John Largess and resonant, natural engineering on all three selections, and we’ve got a vital, illuminating release that, yes, makes demands of the listener—but it offers payoffs that fully reward the investment.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Alberto Ginastera, Kiera Duffy, Pentatone