Visual Arts Review: Honoring Martin Puryear at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

By Trevor Fairbrother

I found it remarkable to explore the exhibition, then experience a kind of filmic audience with the artist, then return, fired up and enlightened, to the beautiful installation.

The first room in the exhibition Martin Puryear: Nexus. Photo: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Martin Puryear: Nexus is a survey exhibition on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, through February 8. Co-organized by the MFA and the Cleveland Museum of Art, it features more than 50 sculptures, drawings, and prints made between 1966 and 2023. The MFA’s old-school modernist presentation conjures well-lit, white-walled open spaces that give wondrous presence to the largest objects.

Now in his mid-eighties, Puryear rose to critical attention in the 1970s with a fresh and timely approach to abstraction that favored a hands-on approach and natural materials. The juxtaposition of three early works in the first room at the MFA demonstrates his reductive yet texturally rich aesthetic. Bound Cone (1972-73) is comprised of two attenuated shafts of aged red oak tightly and immaculately bound by hemp rope. Some Lines for Jim Beckwourth (1978) features pieces of twisted hairy rawhide that differ in length, color and fuzziness; they are carefully attached to the wall as taut, evenly spaced horizontals. Self (1978) is a tall, human-scaled entity; from a distance it suggests a lustrous black stone shaped and smoothed by the environment, but close inspection confirms that it comprised of many lengths of wood, all molded and smoothed in the manner of boatmaking.

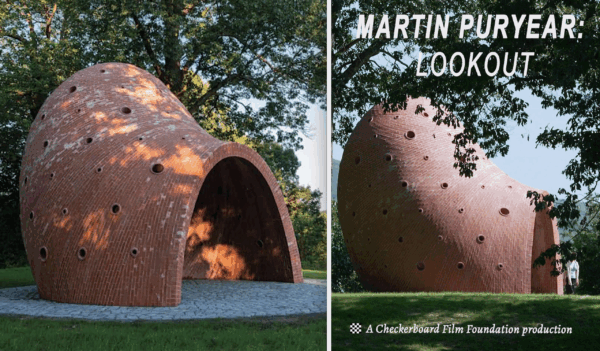

Martin Puryear’s Lookout (2023) at Storm King Art Center. Checkerboard Film Foundation Inc. Photos cropped and paired by the author.

In 1987 Puryear told an art critic for the New York Times, “I’m basically kind of a maverick. … I really feel like an outsider. I never felt like signing up and joining and being part of a coherent cadre of anything, ideologically, or esthetically, or attitudinally.” He insisted he was ”absolutely not a Minimalist” because he had no interest in making objects that feel impersonal, pure or industrially fabricated. Writing in Artforum in December 1991, Judith Russi Kirshner, gave these comments a seemingly negative spin: “[Puryear] is uncomfortable with ethnic, national, or racial categories and formulas and has removed himself from today’s overt political expressions of racial community and social agendas.” Decades later there is much evidence to argue that Puryear’s art often reflected the socio-cultural tensions of the times, with subtlety and without scapegoating.

Puryear was the first of seven children raised by middle-class African American parents in racially segregated Washington, D.C. His father worked for the Post Office and his mother was an elementary school teacher. In his youth he built canoes and furniture, emulating his father’s interest in carpentry. He entered Catholic University of America in 1960; in his junior year he switched his major from biology to painting. When he served in the Peace Corps (1964-66) he was sent to Sierra Leone to teach science, languages and art; during his West African sojourn he visited potters, weavers and woodcarvers. From 1966 to 1968 he lived in Stockholm and studied printmaking at the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts. Many of these experiences reinforced Puryear’s admiration for people working in vernacular traditions. In 1971 he received his MFA from the graduate sculpture program of Yale University. For the next eight years he supported himself as a teacher at Fisk University, the University of Maryland, and the University of Illinois, Chicago.

Confessional, 1996–2000, Martin Puryear. Photo: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The ways in which Puryear devises titles for his works sheds light on his artistic point of view. While he is deeply committed to giving viewers a handle, he also strives not to impose limits on how a work is experienced. He once said that he does not want a title to be a door to a tiny room. Some Lines for Jim Beckwourth is a good example. The sculpture is named for a multiracial trapper and trader born into slavery in Virginia in 1798; he lived for several years with the Crow Nation and adopted Native American dress; he was eventually recognized as a notable figure when the civil rights movement boosted awareness of Black American history. Thus, Puryear’s abstract arrangement of “lines” in this work may allude to a musical or poetic frame for the celebration of an impactful person of color. Self, which the MFA has installed near to the Beckwourth work, represents the other side of the spectrum: it uses a blunt single-word title. In an interview published in 1984 Puryear advised against reading the tall monolith as an extension of portraiture and stressed the more abstract and symbolic notion of selfhood: “It’s meant to be a visual notion of the self, rather than any particular self – the self as a secret entity, as a secret hidden place.”

After scanning the entire exhibition, I realized that Self is a striking example of a motif that recurs in Puryear’s oeuvre: an ellipse-shaped volume that is curved at the top. Hanging near Self is a richly textured etching depicting a similar dome-topped form. The print (Rune Stone, 1966) dates from the period when the artist lived in Stockholm, and suggests that he took great interest in Sweden’s many Viking-Era raised stones carved with runic inscriptions. The next free-standing curved form that visitors encounter is Bower (1980). It is a hollow wooden frame latticed with thin strips of spruce, with a title that alludes to a natural enclosure for refuge or seclusion.

Midway through the show one confronts Confessional (1996-2000), which is the most unsettling iteration of the sculptural motif on display. It has a frame of steel rods patched over with rectangular pieces of wire mesh. The object’s curved volume is halted abruptly at one end by a vertical wooden front, with details that suggest a door and a stoop or kneeling place. The work has a weirdness worthy of Hieronymus Bosch, and the nature of the confessing it invites is anyone’s guess. The last room of the exhibition is enlivened by a swelling, shapely object that is the antithesis of Confessional. Crafted from red cedar and painted bright red, the work is titled Big Phrygian (2010-14). Puryear is making a joyful nod to the hat known as a Phrygian cap. In ancient Iranian, Greek and Roman cultures the soft, conical headdress was worn with its apex bent forward. It had become an international emblem signifying the pursuit of freedom by the time of the French Revolution. When the artist represented the United States at the Venice Biennale in 2019, Big Phrygian was part of an exhibition that he named Liberty/Libertà. The centerpiece of the project was A Column for Sally Hemings (2019), an homage to a Black enslaved woman who lived on President Thomas Jefferson’s estate in Virginia. Hemings was the mother of at least six of Jefferson’s children. Puryear’s sculpture combines a white fluted column and a cast-iron stake sporting a ring-shaped shackle. Near the end of the MFA’s show a 2021 version of the Hemings work stands near to Big Phrygian.

The last room in Martin Puryear: Nexus. Photo Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Martin Puryear: Nexus is aptly named, for, as noted, it invites viewers to make visual connections, including the group that runs from Rune Stone to Big Phrygian. The artist once commented that he likes a given work to be indebted to several sources: “I like a flickering quality, when you can’t say exactly what the reference is.” He also recognized a certain circularity in his artistic advancement: “I feel like my path is like a spiral in that you’re coming back at a different time to a familiar place.”

In a screening room adjacent to the last gallery one can view Martin Puryear: Lookout, a lyrical 28-minute film from 2023, directed by Susan Wald, Edgar Howard, and Thomas Piper. It touches on the artist’s sense of his spiral path as it documents the genesis of a permanent site-specific work for Storm King Art Center, the 500-acre sculpture park in New York’s Hudson Valley. Puryear is encountered in his studio and engaging with collaborators on site during the construction of his 20-foot-high work titled Lookout. It is a privilege and a revelation to see the quietly-spoken artist conferring with engineers and masons as they plan and execute a rebar shell covered inside and out by red clay bricks. Lookout starts as a tunnel and becomes a domed interior pierced by a constellation of small portholes of three different sizes. Regarding the title he chose, Puryear says the work is simultaneously “a physical place, an invitation to observe and engage with the natural world, and a warning.” I found it remarkable to explore the exhibition, then experience a kind of filmic audience with the artist, then return, fired up and enlightened, to the beautiful installation.

It is good to report that the Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA) has published a splendid catalogue for Martin Puryear: Nexus, distributed by Yale University Press. 17 people from the fields of art, architecture, college teaching and museum work contributed texts. Collectively, they direct attention to the global range of the techniques of production and the aesthetic traditions that Puryear draws on. Emily Liebert, the curator of contemporary art at the CMA, insightfully connects the artist’s interests in animals and birds (especially falcons) to his studies of nomadism, trade routes and histories of enslavement; her essay is titled “Martin Puryear’s Joining of Natural and Social Worlds.”

Trevor Fairbrother worked at the MFA from 1981 to 1996. He dedicates this review to the memory of Mario Diacono, an Italian in Boston.

© Trevor Fairbrother 2025