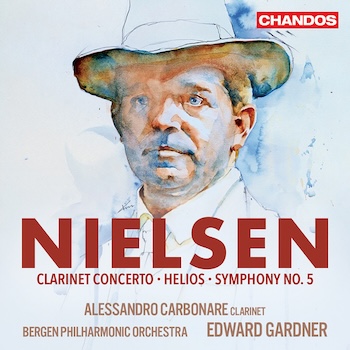

Classical Album Review: Nielsen Clarinet Concerto, Symphony No. 5

By Jonathan Blumhofer

A new recording of Carl Nielsen’s Symphony No. 5 from the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra and Edward Gardner captures much of what makes the composer’s writing in it sound so fresh.

All good art, Toni Morrison once offered, is political—even when it’s not being explicitly partisan. Take Elliott Carter, who described the knotty part-writing in his String Quartet No. 4 as “mirroring the democratic attitude in which each member of a society maintains his or her own identity while cooperating in a common effort.”

All good art, Toni Morrison once offered, is political—even when it’s not being explicitly partisan. Take Elliott Carter, who described the knotty part-writing in his String Quartet No. 4 as “mirroring the democratic attitude in which each member of a society maintains his or her own identity while cooperating in a common effort.”

Carl Nielsen might have been thinking along similar lines when writing his Symphony No. 5 in the years just after World War 1. Then again, maybe not: Nielsen, who spent his six-plus decades living under Denmark’s constitutional monarchy, never said as much and insisted that his score isn’t programmatic.

Nevertheless, the music’s huge plays of contrasts, its vivid dramatic scope, and its wild extremes—the first movement culminating in a partially-improvised snare drum solo that attempts to obliterate the orchestra—has led Simon Rattle to label it Nielsen’s “war symphony.” As such, the Fifth makes for a timely listen in an era of roiling social and political unrest.

A new recording of the work from the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra and Edward Gardner captures much of what makes Nielsen’s writing in it sound so fresh. The symphony’s conversational aspect, its fascinating plays of tone color, its unpredictable voicings and rhythms—all of this comes across with impressive focus. Textures are generally lean, the ensemble’s dynamic range enormous, and tempos move as they should.

Where the reading comes up a bit short is in the expressive department, especially during the opening movement’s ferocious denouement. Here, the Philharmonic’s playing sounds too proper, too nice. The acidic woodwind lines aren’t nearly explosive enough; oddly enough, neither is the big snare drum solo.

In the finale, the ensemble’s technically distinguished playing emphasizes the music’s jarring shifts of tone and mood with visceral energy. Yet, again, there’s a clinical restraint to the interpretation that keeps popping up—the fugue is a touch earthbound, the penultimate Andante a bit restrained—that lends the larger performance an episodic quality.

For comparison, Bernstein’s classic 1962 recording with the New York Philharmonic (still probably the most exciting Nielsen Fifth on record) navigates these issues with more abandon and style. So do more recent traversals from Alan Gilbert (also with the New Yorkers) and Fabio Luisi with the Danish National Symphony Orchestra. For all its strengths, then, Gardner’s is a somewhat underwhelming Nielsen Five.

The composer’s Clarinet Concerto is, if anything, an even weirder entry into the canon than the symphony. Composed in 1927, its four connected movements feature a prominent snare drum part and a parade of unexpected musical characters, textures, and instrumental combinations. The solo part, which is punctuated by two big cadenzas, is breathtakingly virtuosic.

In Alessandro Carbonare’s hands, that line sounds, if not exactly easy, then not unduly taxing. The Italian clarinetist has the concerto’s demands well in hand and he and the Bergen ensemble demonstrate a nice rapport, estimably executing the music’s many exchanges between soloist and orchestra.

Again, the playing of all hands is rhythmically crisp and well-balanced. If the performance might lean into the music’s extremes a bit more aggressively, it offers moments of real personality and color (the second-movement bassoon writing is particularly striking). The closing bars—which sound something like a toy running out of battery—anticipate late Shostakovich by a few decades.

Filling out the album is Nielsen’s Helios Overture, which he wrote after spending some time in Greece during the early 1900s. Gardner leads the Bergen orchestra in a shapely, sweeping reading that dispatches the score’s bustling counterpoint with the same sense of purpose and precision that it lavishes on the overture’s stately, majestic framing sections. All art may be political, but Helios reminds us that there are bigger, nobler, more enduring and attention-worthy things out there—and we’d do well to dwell on them, if only for the perspective they provide.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Alessandro Carbonare, Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra, Carl Nielsen, Chandos