Arts Remembrance: Jack DeJohnette — As Much a Colorist as a Drummer

Jack DeJohnette — who died this week at age 83 of congestive heart failure — lorded over his entire kit with loose but incisive strokes to tightly tuned drum heads and cymbals.

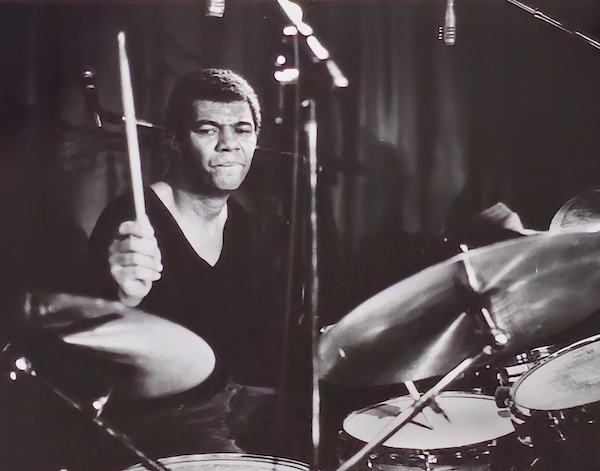

Jack DeJohnette at Jonathan Swift’s with Special Edition in 1979. Photo: Paul Robicheau

Jack DeJohnette’s drumming propelled many of the greatest combos in the evolution of jazz. He remained best known for cutting funky rock beats behind Miles Davis on fusion landmarks like Bitches Brew. But DeJohnette also injected impressionistic swing into Keith Jarrett’s three-decade standards trio, joined Pat Metheny and Ornette Coleman in their free-jazz summit Song X, and made several albums with Charles Lloyd and Sonny Rollins, in addition to leading his own bands.

Throughout his tenure, DeJohnette — who died this week at age 83 of congestive heart failure — lorded over his entire kit with loose but incisive strokes to tightly tuned drum heads and cymbals. He punctuated music with both percussive and melodic tones, reflecting the orchestral approach of piano, his first instrument.

“It’s like a painter with a palette,” DeJohnette told me in 2015. “I think of myself more as a colorist than a drummer.”

His journey began in Chicago, where DeJohnette began classical studies as a child. “My uncle was a jazz DJ, so I had access to a lot of jazz records,” said DeJohnette, who was drawn as a teenager to a drum kit left in the family home and joined the school concert band. “Within a month, I developed coordination on [the drums] and just kept working at it,” he said. “I practiced four hours on drums and four hours on piano and over time, I started working [professionally] on both.”

While he played piano in small jazz groups, the drums took the forefront, leading to time with the Sun Ra Arkestra and saxman Eddie Harris. He briefly played with John Coltrane in the sax icon’s mid-1960s ensemble with co-drummer Rashied Ali, the groundwork laid by sitting in with Coltrane’s legendary quartet. “My first time playing with him was being in the right place at the right time, in a small club in Chicago, when Elvin [Jones] was late for the last set,” DeJohnette said. “The owner told Coltrane that I was a good drummer and let me sit in. So, I got to play three tunes with the quartet. Of course that was a very confidence-building experience.”

He carried that confidence into work with saxophonist Charles Lloyd (including his popular 1966 live album Forest Flower, which attracted a crossover audience) and pianist Bill Evans, setting up his groundbreaking run with trumpeter Davis’s electric band, which also included Live-Evil, Jack Johnson, and On the Corner. “[We’d] try different things, finding the groove ’til he liked it and he played over it or cued someone else,” said DeJohnette, who was joined by pianist Jarrett from Lloyd’s group and bassist Dave Holland, who became a later collaborator as well.

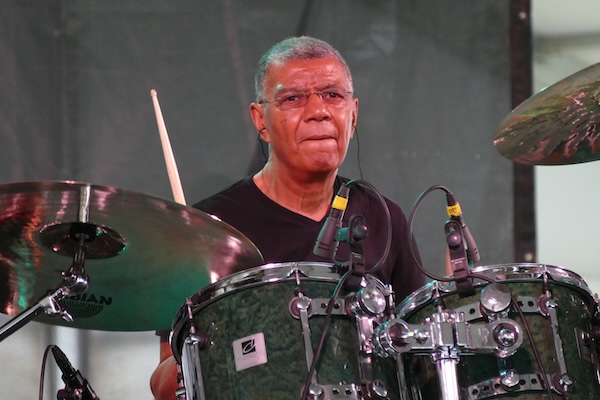

Jack DeJohnette at Newport Jazz Festival with Hudson in 2017. Photo: Paul Robicheau

As a bandleader and composer, the drummer made his solo debut in 1968 with The DeJohnette Complex. But he blossomed in atmospheric ’70s settings for the ECM label, with John Abercrombie on the guitarist’s Timeless (with keyboardist Jan Hammer) and two albums by their trio Gateway (co-led with Holland), its first record both expansive and explosive. Abercrombie also took part in DeJohnette’s fusion-leaning band Directions, while the drummer honed compositional space in his chamber-like group Special Edition, which highlighted twin saxes, introducing David Murray, Arthur Blythe, Chico Freeman, and John Purcell across four albums.

DeJohnette also drummed on records by Chick Corea, Joe Henderson, Cannonball Adderley, Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, McCoy Tyner, Herbie Hancock, George Benson, Alice Coltrane, Michael Brecker, Dave Liebman, and Wadada Leo Smith, in addition to his solo pursuits, which included 1985 and 2016 albums on piano.

The 2012 recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master Fellowship also won a 2009 Grammy Award for Best New Age Album with his meditative Peace Time, followed by one in 2022 for Best Jazz Instrumental Album with Skyline, featuring pianist Gonzalo Rubalcaba and bassist Ron Carter.

DeJohnette’s projects also ranged from 2015’s Made in Chicago (with avant-garde hometown comrades Henry Threadgill and Roscoe Mitchell on saxes) to 1992’s fusion outing Music for the Fifth World (including Living Colour guitarist Vernon Reid and drummer Will Calhoun) and 2012’s Latin-tinged Sound Travels, which featured such emerging players as guitarist Lionel Loueke, trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire, and singer/bassist Esperanza Spalding, the 2011 Grammys’ Best New Artist. One of his last bands was a trio with sax scion Ravi Coltrane and electric bassist Matt Garrison, whose father Jimmy played acoustic bass in the John Coltrane Quartet.

“You can see a continuation of the musical legacy,” DeJohnette said, adding of his own multigenerational pursuits, “It’s part of the tradition. Like any art form, you pass things on.”

— Paul Robicheau

“Sound” in jazz refers both to the notes a musician plays, the style, if you will, and to the actual timbre and resonance of the instrument. Although the two are inextricably linked, there are drummers who pay more attention to the latter — at least their choices align with my own aesthetics –and those are the drummers I’m most drawn to.

I knew very little about Jack DeJohnette when I first heard him play around 1969, with saxophonist Sam Rivers. I immediately thought there was something attractive and distinctive about his playing, but it took me a while to understand why: It was the musicality of his drums.

A drummer selects his or her drums and cymbals, but that’s just the beginning. The pitch of the drums and the resonance of the cymbals can be fine-tuned to create a sound that is both self-contained and accessible, even inviting, to the other musicians on the bandstand. There has to be space available within the sound. Each object in the kit has to reflect the others in a harmonious way so that one gets the feeling that they are engaged in a dance.

Of course, DeJohnette was also a pianist and was aware not only of rhythm, but harmony and melody and he brought that into his playing as much as any other jazz drummer ever has.

— Steve Provizer

A few words could never suffice, and yet a library-full would not do him justice.

No percussionist before him was so versatile, so flexible. He was like the elephant encountered by a troupe of six blind men in the ancient tale from the Subcontinent: each perceived something different about the creature and not one of them could perceive the whole.

The king is dead. Long live his swing.

— Steve Elman

Here are three instances of drum mastery by Jack DeJohnette: 1) with Keith Jarrett and Gary Peacock, 2) with Bennie Maupin and Jason Moran, and, 3) with Hudson, an ensemble made up of John Scofield, John Medeski, Larry Grenadier, and DeJohnette. At Zellerbach Auditorium on the University of California, Berkeley campus, DeJohnette played with such unparalleled accuracy and precision that I completely forgot about his bandmates. At Yoshi’s in Jack London Square, Oakland, DeJohnette rolled out the funk in a concise manner, never to be duplicated. Finally the shocker, at the SF Jazz Center, Hudson played “Up on Cripple Creek” and DeJohnette sang the lyrics while rocking to The Band’s great song. No matter the situation, DeJohnette’s ability to adapt and to elevate the music was unprecedented.

— Brooks Geiken