Opera Album Review: World-Premiere Recording of a 1760s Opera about . . . Norway

By Ralph P. Locke

First-rate performances, including by a Norwegian orchestra and conductor plus superb international singers, make this one a winner.

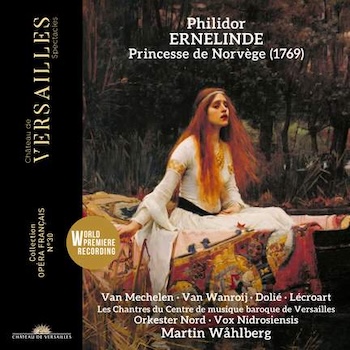

PHILIDOR: Ernelinde, Princesse de Norvège

Jehanne Amzal (Norwegian woman ; High Priestess), Judith van Wanroij (Ernelinde), Reinoud Van Mechelen (Sandomir), Matthieu Lécroart (Ricimer), Thomas Dolié (Rodoald), Martin Barigault (Ricimer’s officer, High Priest), Clément Debieuvre (Norwegian man, sailor, Edelbert).

Chorus of the Versailles Baroque-Music Center, Orkester Nord, cond. Martin Wåhlberg.

Versailles Spectacles 161 [2 CDs] 138 minutes. To purchase or try any track, click here. The entire release is also on YouTube, open-access.

Versailles Spectacles 161 [2 CDs] 138 minutes. To purchase or try any track, click here. The entire release is also on YouTube, open-access.

The past few decades have seen a dozen or more releases of albums devoted entirely to music of someone simply labeled “Philidor,” and a few more in collections. But one can be easily confused (I was), as three relatives shared this last name: the father André Danican Philidor (often called “the elder”), André’s son Anne Danican Philidor (who was indeed male, despite the first name), and Anne’s half-brother François-André (1726-95).

The last of these wrote the work that we have here. Julian Rushton states, in OxfordMusicOnline.org: “Although he was best known to his contemporaries as a chess player, his stage works show him to be one of the most gifted French composers of his generation.” (The front and back covers, by the way, list only his family name, just to add to the confusion.)

I anticipated much delight when I received the recording for review, because the performers are among the most capable and imaginative currently working on eighteenth-century French opera. The Oslo-based orchestra and its conductor Martin Wåhlberg astonished me in their recording of Grétry’s Raoul Barbe-Bleue (review here). The wonderful baritone Matthieu Lécroart is particularly good at playing nasty roles (such as the title character in that Grétry opera) while still singing rather than snarling or shouting, and he returns here to do the same as the tyrant Ricimer.

The remarkable high tenor Reinoud Van Mechelen, whose performances I have several times praised in reviews here, applies his secure voice and much artistry to the role of the hero Sandomir. Much-recorded soprano Judith van Wanroij sounds freer than sometimes, though with a trace of wobble on many long notes; I hope she’ll figure out how to keep it in check. She takes the title role of Ernelinde, the Norwegian princess over whom Ricimer and Sandomir struggle, in the usual operatic manner. (The opera unfolds in the royal castle, called Nidaros, in Trondheim.) Bass Thomas Dolié plays the fourth main character: the Norwegian king Rodoald, who finally allows his daughter to marry her true love Sandomir and threatens to kill the evil Ricimer, who, humiliated, commits suicide. The work ends with a chorus featuring an important part for the joyful Sandomir. Across the three acts, the capable librettist, Antoine Poinsinet, makes room for several duets (some with chorus) and an impressive “quarrel” quartet at the opera’s midpoint (partway into the second of three acts).

(Since I’ve largely praised the four main singers, I should add that three of them–van Wanroij, Lécroart, and Dolié–have voices that are pale at the low end. This is a widespread problem today, as the seasoned opera critic Conrad L. Osborne has pointed out in his oddly structured but important book Opera as Opera, which I praised highly here.)

The opera was first performed in 1767, and we hear it in a version from two years later that was retitled with the name of the hero instead of the heroine (Sandomir, Prince de Dannemarck). We are not told in any detail what the differences are between 1767 and 1769, and, somewhat confusingly, the work’s original title is restored.

Given the work’s date of composition, one is not surprised that the musical style roughly resembles what Mozart would compose in his early operas (or even, at times, in The Abduction from the Seraglio, 1782) or, for a closer comparison, what Grétry and Gluck were doing in their French operas of the 1770s. Rushton explains: “The arias, long by French standards, are direct in style. Ernelinde fulfilled an Encyclopedist ideal, reconciling French forms with Italianate music.”

Martin Wåhlberg conducting the Orkester Nord in a performance of Philidor. Photo: courtesy of Orkester Nord

The French element to which Rushton refers is seen most clearly in the numerous choruses, orchestral numbers (duets, etc.) in which the chorus participates; the Italian element, in the sometimes rather florid vocal lines and in the use of the basso continuo rather than the orchestra to accompany the recitatives.

But I’ve just put the matter too simply. As the booklet-essay explains, the continuo part is here accompanied by harpsichord and not one cello but two or three plus a double-bass, and one of the cellists plays chords, following a practice that the Versailles Baroque Music Center has noticed in the surviving performing parts. The net result is to “Frenchify” somewhat the recitatives, and give them more dramatic punch.

One of the most impressive solo numbers is Sandomir’s six-minute accompanied recitative and lament-aria that begins Act 3 (he has been imprisoned by Ricimer). The booklet points out that the surviving manuscripts show ornaments written out in detail–another Italianate feature–instead of being indicated with a symbol (such as a plus sign), as had long been normative in France.

Philidor made a later version of the work (1777) that is reportedly even more Gluckian. Perhaps this could be recorded next, for comparison. Also, some dances were omitted from the concert performance and subsequent recording. If those remained in the 1777 version and are as lovely and contrasting and as the ones included here, it’ll be a pleasure to hear them!

Soprano Judith van Wanroij. Photo: Interartist

Speaking of the booklet, the translations in it, attributed to an individual (whom I shall not name) and to a firm called LanguageWire, are marred by errors. Some of these are mildly annoying: “principle works” for “principal works”; and the odd phrase “the 1769 version, the first musical edition” apparently means “the 1769 version, which is the first and only one to have been published”.

Other typos create word hash: the phrase “operas from the 1770s and 1780s…” becomes “operas. From the 1770s and 1780s…,” thus turning one perfectly clear sentence into two puzzling ones. This is perhaps the third or fourth time I’ve had to complain about English translations in Versailles Spectacles releases. I promise never to stop complaining.

Still, it’s a wonderful work and recording, with perfectly gauged tempos and highly colorful sounds coming from the Oslo-based chamber orchestra (including brass that snarl without overpowering the strings and woodwinds). Besides the fine singers mentioned earlier, I give a shout-out for the young light soprano Jehanne Amzal, a superb technician, who shines in two secondary roles. She and the two other singers of secondary roles also sing in the Versailles-based chorus, whose work here is unfailingly gorgeous; their director is Fabien Armengaud.

When people ask me about French opera before 1800, I, out of habit, often recommend specific works by Lully, Campra, and Rameau, operas from the decades around 1700, the height of the Baroque era. But the wonderful recordings that are coming out now of works by Grétry, Philidor, and of course Gluck, Salieri, Spontini, and others, increasingly allow me to expand my recommendations to include splendid works from the mid and late 1700s as well. I urge every opera lover to get to know Philidor (well, this Philidor, at least) and his stirring Ernelinde (or, if you prefer, Sandomir).

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music and Senior Editor of the Eastman Studies in Music book series (University of Rochester Press), which has published over 200 titles over the past thirty years. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, The Boston Musical Intelligencer, and Classical Voice North America (the journal of the Music Critics Association of North America). His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and is included here, lightly revised, by kind permission.