Jazz Album Review: A Flowering of Charlie Rouse’s “Cinnamon Flower”

By Michael Ullman

A rare chance to listen to saxophonist Charlie Rouse with a biggish band, the new Cinnamon Flower is a welcome set.

Charlie Rouse, Cinnamon Flower: The Expanded Edition (2 LPs, Resonance Records)

Recorded in 1977, this two-LP “Expanded Edition” combines tenor saxophonist Charlie Rouse’s Cinnamon Flower as it was first issued, with its original mix, and a version without producer Alan Douglas’s subtle overdubs (strings, bells, and whistles), along with previously unreleased studio tracks. A bonus is the previously unissued “Meeting House,” a delightfully cheery tune that was composed by and — as is true of much of the rest of the set — arranged by Dom Salvador. (Two cuts are arranged by Amaury Tristao.) Nineteen musicians are listed as taking part in the session. The shifting personnel of Brazilians include legendary percussionist Portinho; the Americans feature Ron Carter, Albert Dailey, and Ted Dunbar, among others

Recorded in 1977, this two-LP “Expanded Edition” combines tenor saxophonist Charlie Rouse’s Cinnamon Flower as it was first issued, with its original mix, and a version without producer Alan Douglas’s subtle overdubs (strings, bells, and whistles), along with previously unreleased studio tracks. A bonus is the previously unissued “Meeting House,” a delightfully cheery tune that was composed by and — as is true of much of the rest of the set — arranged by Dom Salvador. (Two cuts are arranged by Amaury Tristao.) Nineteen musicians are listed as taking part in the session. The shifting personnel of Brazilians include legendary percussionist Portinho; the Americans feature Ron Carter, Albert Dailey, and Ted Dunbar, among others

A rare chance to listen to Charlie Rouse with a biggish band, the new Cinnamon Flower is a welcome set. (I am listening on LP. The album is also available on a single CD and as a download.) Rouse, who died in 1988 at the age of 64, made over a dozen recordings as a leader, starting with the 1957 date The Chase Is On. Nonetheless, I believe he will always be first remembered for his work with Thelonious Monk; for 11 years, starting in 1959, Rouse was the saxophonist in the Thelonious Monk Quartet. With Monk he made over 20 albums, beginning with At Town Hall (1959 Riverside) and ending in 1969 with Monk’s Blues (Columbia). Set against the wonderful, slightly eccentric playing of Monk, Rouse sounded more than a little square; he seemed to be about holding down the fort. During the same period, Rouse was a sideman on a number of celebrated recordings, such as Clifford Brown’s Memorial Album, Benny Carter’s Further Definitions, and Sonny Clark’s Leapin’ and Lopin’. After Monk’s passing, Rouse co-led Sphere, the traveling tribute to Monk that during the ’80s made half a dozen recordings.

Saxophonist Charlie Rouse. Photo: Raymond Ross / CTSIMAGES

As he demonstrates in Cinnamon Flower, with its Brazilian tinge, Rouse could do a lot of things besides convincingly play “Blue Monk” and “Five Spot Blues,” worthy though that endeavor was. Rouse sounds (mostly) gentler here than with Monk. He plays a short solo intro to “Roots” without the edge he brought to Monk. There is no outright title cut. The closest to one is Milton Nascimento’s “Cravo e Canela” (Clove and Cinnamon) with its tightly played ensemble and solos by pianist Dom Salvador, trumpeter Claudio Roditi, and Rouse, who supplies engaging rhythmic variations. He fades out here, rather than come to a rousing conclusion. Dom Salvador’s “Backwoods Echo” begins with Rouse playing solo over acoustic guitar. The surprise is when the full ensemble comes crashing in. Rouse solos effectively and then Roditi enters exuberantly, with trills and darting short phrases. “A New Dawn” has a particularly memorable melody. It opens with solo guitar over spare percussion and birdlike sounds by the flute. The melody is limned first by flutist Lou Orenstein and then by the ensemble. The track displays Rouse’s willingness to lay back and not to dominate the music. His solo, though, fits nicely into the active rhythms his band is laying down.

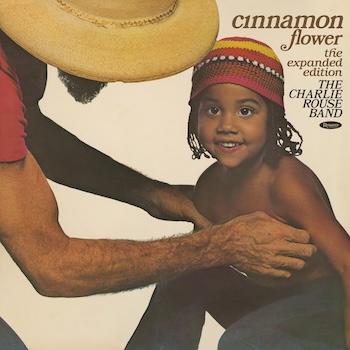

I was surprised to read that Dom Salvador’s “Quiet Pictures (Natal no Interior)” was the product of depression. The composer had recently arrived in Manhattan, it was Christmas, and his family had yet to join him. (The situation sounds like a Jimmy Stewart movie.) Salvador made the best of his time alone by composing. Unusually, the opening bars of the (nondepressive) melody is played by cellist Jesse Levy. The rhythm section is upbeat as always, and Rouse seems to glide over the ensemble, which continues to play deftly underneath him. The unadorned studio album is quieter: the ensemble keeps its distance. An advantage is we get to hear Ron Carter’s bass lines clearly. It’s a more contemplative piece in the studio version, which I prefer. Similarly, the studio version of “Clove and Cinnamon” sounds more contained. In this case, I like the exuberant version that appeared on the original album. Others will no doubt disagree. I was grateful for the chance to listen to both the studio and originally issued versions on these clean, precise LPs. A bonus: the original cover to Cinnamon Flower features a photo of what must have been the cutest little girl in the world. In the new package, she appears again: sticking her tongue out at us.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 30 years, he has written a bimonthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. He is emeritus at Tufts University where he taught mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department.

Tagged: "Cinnamon Flower", "Cinnamon Flower: The Expanded Edition", Charlie Rouse