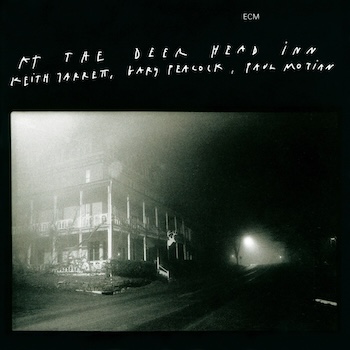

Jazz Album Review: Keith Jarrett Trio — “At the Deer Head Inn: The Complete Recordings”

By Michael Ullman

At the age of 80, pianist Keith Jarrett can no longer perform, but his legacy is secure. At the Deer Head Inn is a significant part of it.

Keith Jarrett Trio, At the Deer Head Inn: The Complete Recordings (ECM, four LPs)

Keith Jarrett was raised in Allentown, Pennsylvania, less than forty miles from Delaware Water Gap in the Poconos, where the Deer Head Inn jazz club is located. The Deer Head now bills itself as the oldest continuously running jazz club in the country. Despite its obscure location, in the ’80s and ’90s the venue became known among musicians as a place to jam. In a video, alto saxophonist Phil Woods says that, when they were working in the area, “it always ended up at the Deer Head.” Woods describes the club as “a good place to work out what you are going to do.” He makes the Inn sound both relaxed and welcoming, its engaged audiences open to experimentation. When he was playing there, Woods widened the Inn’s reputation: at first, his musician friends didn’t know where it was, or why it mattered. The club’s place in history was sealed, however, when Keith Jarrett recorded At the Deer Head Inn with bassist Gary Peacock and drummer Paul Motian.

Keith Jarrett was raised in Allentown, Pennsylvania, less than forty miles from Delaware Water Gap in the Poconos, where the Deer Head Inn jazz club is located. The Deer Head now bills itself as the oldest continuously running jazz club in the country. Despite its obscure location, in the ’80s and ’90s the venue became known among musicians as a place to jam. In a video, alto saxophonist Phil Woods says that, when they were working in the area, “it always ended up at the Deer Head.” Woods describes the club as “a good place to work out what you are going to do.” He makes the Inn sound both relaxed and welcoming, its engaged audiences open to experimentation. When he was playing there, Woods widened the Inn’s reputation: at first, his musician friends didn’t know where it was, or why it mattered. The club’s place in history was sealed, however, when Keith Jarrett recorded At the Deer Head Inn with bassist Gary Peacock and drummer Paul Motian.

Previously reissued on CDs, At the Deer Head Inn: The Complete Recordings are now available in a neat box of four ECM LPs. All fifteen of the tracks on the set, mostly standards, were recorded on September 16, 1992. Jarrett was then in his mid-forties. In jazz terms he was a veteran, and was celebrated. He’d been in the business since the ’60s. The pianist had recorded in 1966 with Art Blakey (Buttercorn Lady) and then made a series of popular albums with Charles Lloyd, including Forest Flower (also from 1966), made when he was barely old enough to legally enter clubs. (He was born on May 8, 1945.) He has recorded close to two hundred sessions since, including a series of classical albums, playing music by Bach, Bartók, Shostakovich, and Lou Harrison. His Koln Concert is said to be the best-selling solo piano record in jazz.

The Deer Head Inn recordings are special. The setting feels intimate. The trio is recorded close up and brightly. (Just for the sound, these newly issued LPs are worth acquiring, even if you, like me, own the CD versions.) The trio is practiced and audibly comfortable with each other. Their talents mesh. Bassist Peacock was a most flexible musician. Besides being part of Jarrett’s Standards Trio, he recorded widely with pianists like Bill Evans, Paul Bley, and Chick Corea. He was adept enough to switch hats and also record with avant-gardists like Albert Ayler, who would seem to be the antithesis of Bill Evans. Paul Motian is probably best known for his subtle playing with that same Bill Evans: he appears on, for instance, Evans’s iconic Portrait in Jazz (1959). His appeal never flagged. Much later, Motian would play on sessions by pianists Geri Allen and Marilyn Crispell.

The performances at the Deer Head Inn, and even the choice of repertoire, feel spontaneous. At the end of several tunes, you can hear Jarrett suggest what they should play next: “How Long Has This Been Going On,” for instance, after “Golden Earrings.” There was apparently no overall plan. The sets open with Miles Davis’s “Solar,” which had already become a jazz standard after Miles introduced it in 1954. Jarrett enters musingly, solo, and with plenty of pedal as well as crisp one-note lines. He then brings in the band, eccentrically. During his introduction he stops momentarily, then rambles on a bit more, as if undecided. Finally, almost two minutes into the track, he plays the sprightly melody and the trio instantly falls into line. We hear Motian doing a lot of things besides keeping the beat, and Peacock rushing lines as if to squeeze himself into the conversation, before he retreats. The bassist’s timing is impeccable. Jarrett bends the harmonic structure of his tunes at will, which creates a distinctive kind of excitement. The repertoire here seems whimsical. Jarrett follows “Solar” with a surprise; a slow, bluesy version of “Basin Street Blues,” whose melody is stated in alternating phrases with Peacock. (Keep in mind Jack Teagarden’s lazy-bones vocal version from 1931. I am guessing that Jarrett did, as well as Miles Davis’s popular recording.)

Drummer Paul Motian (r) and Keith Jarrett (l) Photo: ECM

Not all the standards Jarrett plays are currently well known. Composed by Victor Young for a movie with that name, “Golden Earrings” was made into a jazz hit by Peggy Lee’s 1947 recording, though later Frank Sinatra (and others) also recorded it. Its lyrics are silly enough: “There’s a story the gypsies know is true/ That when your love wears golden earrings/ He belongs to you.” It’s unclear if, in general, the golden earrings are meant to attract, or merely to retain, a loved one. “Golden Earrings” is played here with a kind of sparkle, as if the promised love had already arrived.

Several of the Deer Head Inn pieces, besides “Basin Street Blues,” are connected with Miles Davis, including “Bye Bye Blackbird.” (Davis recorded “Bye Bye Blackbird” in 1957.) Jarrett begins “Blackbird” in a relaxed fashion, as if deciding what he is about to play. Eventually, he announces the familiar melody with emphatic single notes. He ends the opening chorus in similar fashion, and then relaxes into his improvisation. He’s a master at manipulating the tension of a performance, inventing lightly tripping lines that go outside the written harmonies. When the performance is going well, Jarrett involves his left hand in block chords. The pianist’s solos are a sequence of sprightly, unexpected ideas: at one point in “Blackbird,” drummer Motian (I believe) yells, “Go!”

Jarrett begins “Someday My Prince Will Come” in an almost dreamlike fashion. Peacock solos first; Motian’s brushes are prominent on this cut. Jarrett plays most of a chorus in block chords. The trio takes on a much less well known ballad, “Chandra,” which was recorded by another pianist, Jaki Byard, on the latter’s Sunshine of My Soul. Jarrett’s tribute to Thelonious Monk is a powerfully stated, uptempo “Straight, No Chaser.” Immediately, via his ensuing solo, Jarrett moves far beyond Monk’s chords. He makes it sound effortless. Pat Metheny once told me, when Jarrett was already famous, that he thought the pianist was the most underrated figure in jazz. At 80, he can no longer perform, but his legacy is secure. At the Deer Head Inn is a significant part of it.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bimonthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: "At the Deer Head Inn: The Complete Recordings", Gary Peacock, Keith Jarrett