Book Review: “The Letters of Frank Loesser” — The Illuminating Correspondence of an American Musical Master

By Steve Provizer

The letters of this protean figure in American musical theater induced in this reader a pleasurable mixture of nostalgia, voyeurism, and insight.

The Letters of Frank Loesser, edited by Dominic Broomfield-McHugh and Cliff Eisen. Yale University Press, 672 pages, $35.

In 20th-century America, musical theater was a force to be reckoned with. Broadway, of course, was the epicenter, but stage companies crisscrossed the country to perform shows, just as vaudeville troupes had earlier in the century. Hit musical creators and actors moved in rarified circles, showing up on television shows as panelists and mystery guests and traveling between the coasts as film versions were made of their hit shows. By mid-century, it was hard to find a home in America whose record collection didn’t include cast recordings of musicals like Annie Get Your Gun, Kiss Me Kate, South Pacific, and Oklahoma.

In 20th-century America, musical theater was a force to be reckoned with. Broadway, of course, was the epicenter, but stage companies crisscrossed the country to perform shows, just as vaudeville troupes had earlier in the century. Hit musical creators and actors moved in rarified circles, showing up on television shows as panelists and mystery guests and traveling between the coasts as film versions were made of their hit shows. By mid-century, it was hard to find a home in America whose record collection didn’t include cast recordings of musicals like Annie Get Your Gun, Kiss Me Kate, South Pacific, and Oklahoma.

In the timeline of the evolution of Broadway musicals, Frank Loesser should be placed in the Golden Age, alongside the likes of Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart/Oscar Hammerstein, Cole Porter, Irving Berlin, Kurt Weill, Leonard Bernstein, Betty Comden and Adolph Green, and Lerner and Lowe. The list could be longer, of course. Loesser’s big shows were Hans Christian Andersen, Guys and Dolls, The Most Happy Fella, and How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying. He wrote music for 60 films, composed “Baby It’s Cold Outside,” and collaborated with Hoagy Carmichael on “Two Sleepy People” and “Heart and Soul,” and with Burton Lane on “I Hear Music.”

Loesser’s communicants in this collection of letters include authors, composers, actors, and movers and shakers behind the scenes, including lawyers, agents, record company executives, and patent attorneys. Through these missives, one learns how important a formal (and informal) adviser Loesser was to the next generation of musical theater creators, including Meredith Willson (The Music Man), Richard Adler and Jerry Ross (Damn Yankees, Pajama Game), and others.

To those unfamiliar with Loesser’s biography, the most surprising fact in these letters is that he was very much a businessman, and on an impressive scale. He started a publishing company, Frank Music, that became quite large, with multiple smaller businesses tucked under its umbrella. Loesser made executive decisions and negotiated contracts. He also functioned as kind of a high-end song plugger, working to gin up sales of sheet music — the bread and butter of any musical publishing house — as he negotiated with record companies about who should or shouldn’t sing certain songs, as well as supervising revivals of his shows and backing new productions himself.

A large proportion of the letters here are about business. The density of some letters about rights issues, distribution, etc., would tax most readers, but any theater person concerned with such arrangements could probably mine these for priceless inside info. That said, thanks to the clarity and humor of Loesser’s writing, even the business letters are nearly as interesting as those that deal specifically with creative problems.

To read Loesser’s analyses of shows and scripts is to be instructed by a dramaturgical master, especially in musical theater. His firm grasp of narrative dynamics is apparent in his adroit dissection of plots. He pressed that motivations must be clear, comprehensible, and believable, though heightened for the stage. The potential for audience members to cease suspending disbelief must especially be kept in mind in a genre where, at any moment, someone might break out into song. For all his expertise, Loesser’s own record was not unblemished. He had near misses and even a couple of flops — his post-mortem letters on these failures are razor sharp. He doesn’t spare the rod on his collaborators or on himself.

Loesser, like other mainstream musical creators of the day, was not concerned with politics, either onstage or, if these letters are representative, off stage. In the ’30s, non-Broadway musical theater ventured into more overly leftist politics, with a few union-produced shows such as Pins and Needles and The Cradle Will Rock and the Federal Theatre Project’s Living Newspaper and their Negro Theatre Unit. On Broadway, there was an arc of artistic change, beginning in the ’20s, to cut down on the escapist froth and portray more realistic situations on musical theater stages. Generally, however, if musicals took on politics at all, it was as fodder for light satire, as in Of Thee I Sing, Let ‘Em Eat Cake, or Call Me Madam.

The years just before and after 1950 constitute the McCarthy era — the height of the “Red Scare.” This witch hunt for Communists in showbiz hurt some authors and actors badly, especially those in unions, which HUAC considered de facto communist. But the world of musical theater went through relatively unscathed. In 1954, an allusion to Loesser in an “Un-American Activities story” was met with a full-bore defensive campaign on his part. He traveled to Washington, DC, and met privately with Harold Velde, the Chairman of HUAC, and reached out to influential newspaper and magazine writers to keep himself out of harm’s way. He was a well-known popular artist and had apparently not ruffled the wrong feathers. His crusade was successful.

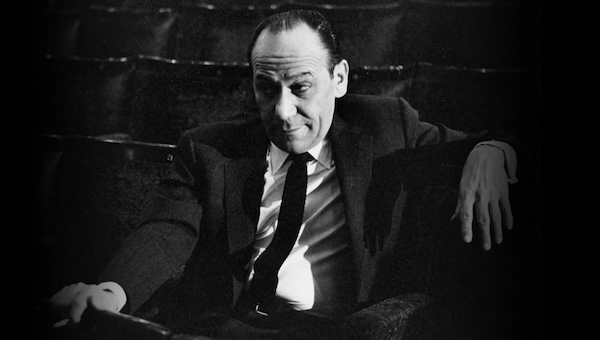

Composer Frank Loesser — a dramaturgical master of musical theater. Photo: frankloesser.com

Understanding the “inner man,” as it were, is not one of the benefits of these letters. Probably about 60-75 percent of the letters are business-related. In these, Loesser wields the carrot and the stick with equal deftness: he is seldom directly confrontational. There were, of course, many Jews in the world of musical theater at the time, including Loesser, and he often throws Yiddishisms into the correspondence. He shows the admirable capacity to adjust his tone, making each recipient feel that Loesser understands their difficulties and, crucially, the solutions he or his company might provide. Loesser was obviously a worrier, but he was not a ruminator. If you’re looking for philosophy you won’t find it here. In his letters, one simply sees Loesser doing — or planning to do — things for his business and/or his family and friends.

The editors have done an excellent job of providing pithy introductory material between letters, giving the reader enough context to understand one half of a communication, which letters inevitably are. Few letters to Loesser have been included. The composer’s clever drawings are interspersed throughout the text.

I have long appreciated Loesser’s mastery of the craft of songwriting. His melodies and harmonic approach are often surprising and have proven to be strong enough to hold up over time. This is probably why I’ve watched Guys and Dolls and How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying as many times as I have. You also have to figure that, if John Coltrane found something in Loesser’s tune “Inch Worm,” there’s probably something there to find. I highly recommend The Letters of Frank Loesser to anyone interested in the history of 20th-century American musical theater. The letters of this protean figure induced, in this reader, a pleasurable mixture of nostalgia, voyeurism, and insight.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.