Music Commentary: Analyzing the Greatness of Brian Wilson’s “God Only Knows”

By Larry Hardesty

I hope this close look makes clear the exquisite craftsmanship that went into “God Only Knows.” But for many of us, the song has a magic that goes beyond the mere exercise of compositional skill, even skill of a very high order.

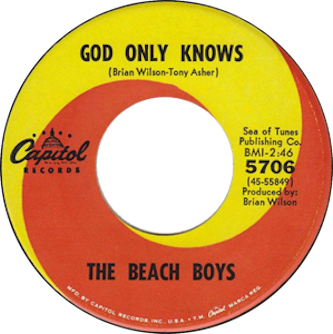

The death last month of Brian Wilson — the founder and leader of the Beach Boys and the composer, arranger, and producer on all their best tracks — was an event of some moment for those of us who still care about that declining genre of music sometimes known as rock. Although his major contributions to popular song ended in about 1966, Wilson remained a titan of the genre, universally acclaimed and widely beloved.

Like most Wilson fans, I have a host of complex thoughts and feelings about the manifold meanings of the Beach Boys’ music and career. But I’m not going to try to make sense of them here. Rather, as one of the many, many songwriters working under Wilson’s influence, I’m going to try to explain why musicians have such high regard for what is generally considered his greatest song, “God Only Knows.”

I’d like to analyze “God Only Knows” according to the standards of the well-crafted song, standards that apply equally to the lieder of Franz Schubert, the classic show tunes of Tin Pan Alley composers like George Gershwin and Richard Rodgers, and the work of the rock songwriters with the greatest interest in compositional form, like Paul McCartney, Ray Davies, and Wilson himself.

To do that, I’ll need to refer to some basic principles of music theory. So here’s a quick primer, which should be easy to follow for anyone who’s ever learned a few basic chords on the guitar or taken a year or two of piano lessons. If you already know the difference between a major and minor triad, you can skip the next three paragraphs.

Most Western music is built around the seven-note major scale — the “Do, Re, Mi” scale familiar to everyone from The Sound of Music. You can begin a major scale on any note, but no two scales share the same notes. On the piano, a scale begun on C uses all white keys, but a scale begun on G requires one black key, a scale begun on D requires two black keys, and so on. Each scale establishes a different key, denoted by the first note of the scale — C major, G major, D major, etc.

A scene featuring the late Brian Wilson in the documentary Long Promised Road.

An interval is the distance between two notes of the scale, measured as the number of scale degrees, including the first and last notes. So, for instance, in a C-major scale, the interval between C (the first scale degree) and E (the third scale degree) is a third, the interval between C and the A above is a sixth, the interval between E and the B above is a fifth, and so on.

A chord is any collection of scale tones played simultaneously, but the principal chords of any key are the three-note chords, or triads, built by combining each of the scale degrees with those a third and a fifth above it. In every major key, there are three major triads, three minor triads, and one diminished triad. I won’t go into the differences, but major triads are generally described as being brighter or peppier and minor triads as being more mournful or sadder. In C major, the three major triads are C (C-E-G), F (F-A-C), and G (G-B-D), and that’s all you need to play “Twist and Shout,” “Sweet Home Alabama,” “Walk of Life,” or any number of other rock songs.

In this article, I’ll first discuss the harmony of “God Only Knows” — the chord patterns — and then the melody — the notes that the lead singer (Carl Wilson) sings. But it’s a somewhat artificial distinction: I’ll need to use melodic concepts in describing the harmony and vice versa.

“God Only Knows” opens with a vamp (a repeated figure) of A major and E major. So what key is it in? E major and A major triads are shared by two keys: E and A. We need a third chord to tell us what key we’re in, so to begin with, we’re in a kind of limbo.

The melody enters, however, on the note D-natural, which occurs naturally in A major but not in E major, which uses D-sharp instead. So we’re in the key of A. Or are we? We seem to be, during the lyrics “I may not always love you / But long as there are,” but over “stars above you,” the harmony moves to a B major chord, which occurs naturally in E major but not in A major.

The melody of the next line — “You’ll never need to doubt it” — begins by alternating between the notes E and D-sharp. So now we’re in E, right? But that same lyric ends, on “it,” on the note C-natural, which occurs naturally in neither A nor E! Where the hell are we? The melody of the final line — “I’ll make you so sure about it” — is derived entirely from the E-major scale, but the chord under “sure about it” uses the note A-sharp — which, again, belongs to neither A nor E. The “it” of “sure about it” falls on the note E, but to my ear, it does not at all feel like the root of our home key.

The melody of the next line — “You’ll never need to doubt it” — begins by alternating between the notes E and D-sharp. So now we’re in E, right? But that same lyric ends, on “it,” on the note C-natural, which occurs naturally in neither A nor E! Where the hell are we? The melody of the final line — “I’ll make you so sure about it” — is derived entirely from the E-major scale, but the chord under “sure about it” uses the note A-sharp — which, again, belongs to neither A nor E. The “it” of “sure about it” falls on the note E, but to my ear, it does not at all feel like the root of our home key.

Finally, the song’s tag line, “God only knows what I’d be without you,” is harmonized with the A-E vamp we heard at the opening. To me, it feels as if we’ve settled in E major, but Wilson does everything he can to forestall that conclusion. The vamp itself, as I mentioned before, could belong to either A or E, and the same goes for the notes of the phrase.

Moreover, the final phrase concludes — on “-out you” — when the vamp is in its A-major phase, so we’re denied the satisfaction of a final arrival at an E-major triad. And the final note of the phrase — F-sharp — belongs to neither the E-major nor the A-major triad. The verse’s end is about as inconclusive as a cadence putatively in E major could be.

It’s probably obvious that all this harmonic ambiguity is the perfect complement to a lyric whose tag line begins “God only knows.” But as Leonard Bernstein argued in his 1973 Norton lecture “The Delights and Dangers of Ambiguity,” ambiguity intrinsically increases music’s expressive capacity: where nothing is definite, everything remains possible.

The melodic structure of “God Only Knows” is every bit as sophisticated as the harmonic structure. To begin with, the melody — from “I may not always love you” all the way through “what I’d be without you” — has no repeated phrases.

What does that mean? Consider the Beatles’ song “We Can Work It Out,” their biggest hit of 1966, the year that the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds (and “God Only Knows”) came out. The verse begins “Try to see it my way / Do I have to keep on talking till I can’t go on? / While you see it your way / Run the risk of knowing that our love may soon be gone.” The melody and harmony of “Try to see it my way” are exactly the same as those for “While you see it your way”, and the same goes for “Do I have to … ,” etc., and “Run the risk of …,” etc.

In other words, the first two musical phrases of the song immediately repeat. This is a perfectly creditable way to compose a pop song: I love “We Can Work It Out.” But refusing to repeat any phrases ups the level of difficulty: the melody runs the risk of meandering aimlessly. Let’s see how Wilson avoids that trap.

One answer is through motivic patterning. Every phrase of the main melody — the first four lines of the song, before we reach the tag line — begins with an oscillation downward by a half-step and back up, followed within a few notes by a melodic leap. This general pattern helps listeners orient themselves within the flow of the melody; at the same time, the pattern changes enough with each iteration to avoid being boring.

For instance, in the first phrase, the oscillation is between D and C-sharp; in the second, it’s between A and G-sharp; and in the last two, it’s between E and D-sharp. The first phrase features a leap downward of a fourth, on “-ways love,” followed by a leap back up by a fourth, while the second phrase features a leap upward of a fourth, on “are stars,” followed by a leap downward of a sixth. The third phrase features the same leap downward by a sixth, which it varies, however, by landing on the C-natural rather than a C-sharp at its end. And the fourth phrase features a leap downward by a fifth, on “sure a-.”

Brian Wilson performing “God Only Knows” in 2017 with the BBC’s “Impossible Orchestra.”

This is fine as far as it goes, but let’s take a closer look at how Wilson keeps the melodic momentum going.

The D that opens the song ends up being the highest note of the opening phrase, while the lowest note is the F-sharp below, at the bottom of the leap, on the word “love.” So after the first phrase, the melody’s total melodic range — the interval between its highest and lowest notes — is a sixth. Within that range, however, only four of the six notes of the A-major scale have been used. Two have been omitted: A and G-sharp.

So what are the first two notes of the next phrase (“as long as there are stars above you”)? A and G-sharp, of course! On the word “stars,” however, the melody leaps up to the F-sharp above the opening D, expanding the song’s melodic range to an octave. At this point, within that octave, only one note of the A-major scale has been omitted: the E below the high F-sharp.

So of course, Wilson begins the third phrase (“You’ll never need to doubt it”) with an E. As I mentioned before, the second note of the phrase is a D-sharp, where previously we’ve had only D-naturals. So at this point, the range of the song is an octave, and the melodic palette — the notes that the melody has covered — includes the six notes shared by the A and E major scales and the two notes unique to them, D and D-sharp.

But as I also mentioned, the final note of the phrase — on “it” — is a C-natural, where previously we’ve had only C-sharps. The range remains the same, but the palette has again expanded.

Finally, on the last phrase of the main melody (“I’ll make you so sure about it”), the melodic range expands upward yet again, to a G-sharp on “sure.” So each of the first four phrases of the song gives us musical information we haven’t previously had, either expanding the range of the melody, filling in omitted notes, or both. This is how Wilson preserves a sense of purpose, of direction, in a melody with no repeated phrases.

The tag line, “God only knows what I’d be without you,” offers a kind of repose, returning us to the vamp of the opening and using only the comfortable notes shared by the keys of both E and A. But even this last phrase expands the melodic range, dropping to the E below the F-sharp that was our previous lower bound.

I hope this analysis makes clear the exquisite craftsmanship that went into “God Only Knows.” But for many of us, the song has a magic that goes beyond the mere exercise of compositional skill, even skill of a very high order. As Wittgenstein said at the conclusion of his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, however, “Whereof we cannot speak, thereof we must remain silent.”

Larry Hardesty is the lead singer and songwriter for the band the Hopeful Monsters, whose song “The Inexhaustible West of the Heart” features a three-line portrait of Brian Wilson. He earns a living as a science writer and editor.

Thank you for this excellent analysis. While much of it is over my head (my musical knowledge consists of having read Classical Music for Dummies, which includes a chapter on music theory) your article provides me with some insight into the complexity of the composition and Brian Wilson’s talent. R.I.P., Brian

Even some vocal training at Cleveland Institute of music and some music appreciation, I’m lost. Thanks for this enlighten post.

Mr. Wilson’s music will live on for new generations to discover. Sadly for me and countless others his music disappeared far too soon. Worst of all I met Mr. Wilson once but I wish I hadn’t.

If you’re lost, can the post really have been enlightening? 🙂

Thanks for your analysis. Just a couple of things: D natural does not appear in the key of A. F# is the ninth in an E major chord and the 6th in an A Major chord and moving between E and A chords is common and not an ambiguous movement. I point these things out because, while Wilson cleverly uses these resources to enrich his music, you’re implying real dissonance. But these notes are, in fact, non-chromatic extensions in common use in many songs.

Stephen, I missed that this thread offers a “reply” option, but I did reply to your comment below.

What you’ve cited is too complex for my novice brain. That’s the beauty of it all . Having someone like me, totally befuddled and a musical aficionado like you & so mamy others give credence to Brian Wilson’s talent, creativity, genius and obsession with beautiful music doesn’t begin to explain the depth of the music world’s loss.

Already so missed, Brian; you live in the hearts of so many

There would be little point in writing music that only people who’d studied music theory in college could understand. Anyone can hear that there’s something remarkable going on in Brian’s music. All we can do is try to shed a little light on what it might be.

What your wrote in that comment is spot on. And your article! I can’t thank you enough. PS-also thanks for reminding us of the Impossible Orchestra whatever-you-call-it. I wanted to see it again and couldn’t find it before seeing your reference. Blew my mind.

Stephen G. Provizer: Thank you for reading the article so attentively!

The key signature for the key of A has three sharps, F-sharp, C-sharp, and G-sharp. Everything else is natural, so D-natural definitely occurs in the key of A. Not sure what you were thinking of there.

You’re right that, in rock music, moving between E and A is common. It’s common in songs in A, where it’s the movement between V and I, and it’s common in songs in E, where it’s the movement between I and IV. The question is, if all you have is E and A, which is it? V-I or I-IV? Without any other harmonies, you don’t know. This is not the ambiguity of complexity, where you amass enough chromaticisms to dislocate the tonal center. You might say it’s the ambiguity of simplicity: there’s just not enough information there to answer the question one way or the other. But it’s still ambiguity!

You’re right that, by itself, adding an F# to an A-major chord is not that exceptional in the music of the period. But find me another ’60s pop song whose melody ends on the second scale degree, over a IV chord. It’s not the use of a non-chord tone in the melody that’s so odd; it’s where and when it happens. (Along with the choice of chord not to comply with.)

Thanks again for your effort. Sorry about the F#–I was thinking about the key of D. Got lost in the woods. For other creative approaches in music of that period, look at Burt Bacharach’s, which is full of “wrong” notes and chords (and odd bar lengths). https://artsfuse.org/268338/music-remembrance-burt-bacharach-stealth-pop-composer/

Yes, I love Burt Bacharach and know his music well. He’s probably the one song composer of the ’60s I would take over Brian, in terms of melodic and harmonic ingenuity. When it comes to “preserving a sense of purpose, of direction, in a melody with no repeated phrases”, “Alfie” is an absolute clinic.

I knew there were multiple deeply profound reasons I liked that song so much and could always listen to it again and again; now I know some of them. Thanks for the Tractus Analysus.

Thanks for reading, Kiril of Macedon.

Welcome to writing for The Arts Fuse, Larry, though this total non-musician doesn’t know what the hell you are talking about it. I will repeat about your article what John Waters has said to me several times about totally opaque books he’s read: “I loved it even though I didn’t understand it!”

Apart from the technical analysis of what makes the song great, I have a bigger question : Did Brian Wilson consciously use a knowledge of music theory to compose the song, or did he write what he felt, and the theory involved was an afterthought for him, if even that? Probably unknowable, but what do you think?

Whether Wilson knew music theory or not, who knows, but I’ve never seen any footage of him with sheet music. His ear heard what he wanted and he transmitted it by singing the parts.

Preston, there are a lot of conflicting stories out there, but I think that the preponderance of the evidence indicates that Brian took several music theory classes both in high school and during his brief stint in community college. How diligent a student he was in those classes is unclear. But I suspect that he absorbed enough basic principles that, given the untold hours that he spent at the piano working out Four Freshmen arrangements, he ended up with a much better functional understanding of theory than most high-school and community college music students have.

For instance, there’s this music professor at Yale, Daniel Harrison, who studies the Beach Boys, and in some essay or other — or maybe it was in Don Was’s documentary about Brian — he discusses one of Brian’s vocal arrangements and says, almost offhand, “and, of course, the voice leading is perfect”. What that means is that both the movement of the individual melody lines and their contrapuntal movement relative to each other follow the voice-leading rules that all music students used to learn in theory class, which are basically a codification of Bach’s practice. It’s hard enough to follow all the rules — to, for instance, avoid all similar motion to perfect consonances — when that’s what you’re trying your damnedest to do. It’s essentially impossible if you don’t know what the rules are.

And Brian did write out parts for the session musicians at his recording dates. He didn’t fetishize musical illiteracy the way some rock songwriters of the ’60s (e.g., Paul McCartney) did.

Now, the degree to which his understanding of theory informed his compositional processes is a different question. Do I think that, when he was writing “God Only Knows”, he thought, “I’ll start with a two-chord vamp to introduce some harmonic ambiguity, and then I’ll answer the question of what key we’re in two different ways in the two different halves of the verse.” No, of course not. He was probably just feeling his way along instinctively. But his instincts had to a large extent been honed by his study of theory.