Visual Arts Review: Great Gallery Shows for Free in NYC – Picasso and Kentridge

By David D’Arcy

Two art exhibitions in New York should be seen multiple times. Each will deepen your appreciation of a great artist. Neither is mobbed with visitors. Each, in this wildly overpriced city, is absolutely free.

The show is presented in partnership with Paloma Picasso, the artist’s daughter. Photo: Gagosian Gallery

The exhibition Picasso: Tête-à-tête at Gagosian Gallery at 980 Madison Avenue declares its inspiration before you enter the galleries — a declaration that Picasso has no single signature style. The curators note that Picasso himself made that point in an exhibition in Paris in 1932. More recent museum exhibitions (at the Musée Picasso in Paris and at the Tate in London) revisited that show. Now we have several rooms of works arranged to prove the point once again. Let’s not forget that, whatever you end up thinking of the curators’ argument, the paintings give pleasure. Lots of it.

Let’s also remember that stages of Picasso’s life were triggered by serial reconstructions of his entourage — new female companion, new house, new poet, new dog, new dealer, and new directions in art. It’s easy to imagine that he didn’t want to be seen as locked into any style, although critics have tagged Picasso’s styles and stylistic periods ever since they began writing about him.

In the first gallery, your eyes are drawn to paintings that Picasso made of Marie-Thérèse Walter, the blonde teenager of 17 whom he encountered in 1927 at Galeries Lafayette in Paris. She had never heard of him. The two began a mostly secret relationship that scuttled Picasso’s marriage to Olga Khokhlova, a dour ballet dancer from Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. His paintings of Olga have a severity that owes much to Paul Cézanne’s portraits of his own wife.

For a decade, Picasso would paint Marie-Thérèse — as a radiant girl, a grand athletic presence, and, later, as a gloomy tangle of asymmetries. She also was at the center of a series of Picasso’s sculptures that explored desire through images of bulbous grotesquery. To put the most positive spin on it, he once again probed the idiosyncratic beauty of sex.

As an artist, Picasso was a forager and an improviser, as seen in pictures from the ’50s of his cluttered studio, where he is seated with his then-young daughter Paloma. Paloma Picasso is an organizer of the show, and a number of works on view from her collection have never been shown in public before.

Pablo Picasso, Femme au vase de houx (Marie-Thérèse), 1937, oil and charcoal on canvas, 28-¾ × 23-⅝ inches (73 × 60 cm), private collection. Photo: Sandra Pointet

Any newly shown Picasso picture is a revelation in some way, but the show mostly confirms what we already knew about Picasso — that he was adept in any medium he tried and was relentlessly playful, even adamant, about frustrating those who claimed to know him and his intentions. He enjoyed whatever confusion he could generate.

We see a 1921 drawing, in red chalk, of his son Paulo — in a style that might have been inspired by Rubens. When Picasso draws young Paloma, more than 30 years later, he uses pencil on paper, eschewing any softness. She gazes out, with intensity, from under a dome of black hair. In a picture on view dated just a year before, he painted a little girl holding a doll in a somber gray monochrome, with a blank, featureless face (Paloma?).

In 1931, around the time when he made delicate portraits of Marie-Thérèse, he also painted The Kiss, a collision of rectangular heads with gaping, interlocking mouths and jagged tongues. Edvard Munch had already painted “Kiss” images in which it was hard to distinguish aggression from tenderness (Love and Pain or Vampire of 1893). In 1969’s The Kiss II, an old bald man — Picasso’s usual stand-in — seems to be throttling a startled woman who looks like the artist’s last companion, Jacqueline Roque.

Picasso would eventually abandon Marie-Thérèse for the dark-haired Dora Marr, his lover during the German occupation of France, whom we see depicted twice in the show — clearly Marie-Thérèse’s visual opposite.

In 1938’s Portrait of a Bearded Man with a Cat, Picasso depicts his powerful dealer, Ambroise Vollard, playing with a cat who isn’t enjoying the fun. The animal could also be a stand-in for any dealer-dependent artist. Vollard would die in a freak accident that some insiders believe was murder. His estate ended up with a Corsican mobster who collaborated with the Nazis.

In a short valediction to the building at 900 Madison Avenue (once Sotheby’s New York hub), which will soon be taken over by Bloomberg Philanthropies, dealer Larry Gagosian (on the gallery’s website) calls the show a blockbuster. Containing 50 works, it’s more of a jewel than a banquet. It’s also an homage to a father from a daughter whom Picasso never saw again after her mother, Françoise Gilot, left the artist and published a damning memoir. Early photographs of Paloma in Picasso’s studio bear witness to a bond that was cut short. Paloma’s brother Claude sued so that he and Paloma would get a share of their father’s estate.

Was that why they’ve been reluctant to show some of the works? All the more reason to see them. Admission is free — go more than once before Picasso: Tête-à-tête closes on July 3.

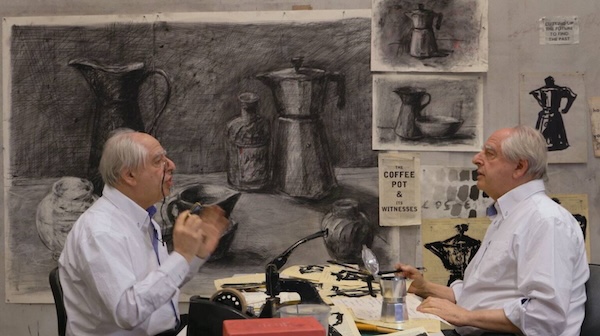

A scene from William Kentridge’s Portrait of the Artist as a Coffee Pot.

Downtown in Chelsea, at Hauser & Wirth New York, is A Natural History of the Studio, a show of works by the South African artist William Kentridge. On view is the artist’s nine-part film series, Self-Portrait as a Coffee-Pot, which the Arts Fuse covered when it premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2022.

The film is many things — a chronicle in and out of Covid isolation, a meditation on artistic creation (with some witty Kentridge soliloquies and a double exposure pair of arguing artists), a charcoal sketch of the South African landscape as reshaped by colonization, and an homage to simple objects, such as the title’s coffeepot. Many of those actual objects are on display here, as if they were props in a theater production. As Kentridge puts it, “You start thinking of drawing a picture of the whole universe, and you end up with a coffee-pot.” Kentridge inevitably reflects on the influence of Giorgio Morandi (1890-1964), a painter who infused transcendence into everyday things. Kentridge’s drawings and objects are shown in two gallery locations.

There’s an added topicality to this show, given current events — or maybe it is the return of an old element. Kentridge’s show opened just before the White House announced that white Afrikaner “refugees” from South Africa (allegedly the victims of Black mistreatment) would be resettled in the United States. Kentridge, the grandson of immigrants from Lithuania, is the son of lawyers who defended victims of apartheid. South Africa, its geography and politics, are often depicted in his work. Also, the land that many white farmers still farm was made available to them through apartheid laws that were passed in the last century. No mention of that in Trump’s list of faux grievances.

The show at Hauser & Wirth, where Kentridge’s massive book of drawings for the Coffee-Pot series can be obtained, runs through August 1. The series can also be streamed.

Overlapping in the Kentridge calendar this spring was a London screening of his film Oh to Believe in Another World, made to accompany Dmitri Shostakovich’s Tenth Symphony. Art under Stalin as a theme today? Just a coincidence.

David D’Arcy lives in New York. For years, he was a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.