Visual Arts Review: “Lighting the Way — South Coast Women’s Lives, Labors, Love”

By Lauren Kaufmann

This exhibition offers much to appreciate about South Coast women, whose lives and accomplishments have played a crucial role in shaping the region.

Lighting the Way: South Coast Women’s Lives, Labors, Loves at the New Bedford Whaling Museum, New Bedford, MA, through May 4.

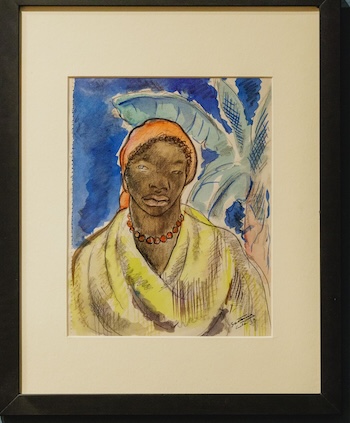

Antonio Gattorno, Afro-Cuban Guajira with a Necklace, 1938. Photo: courtesy of Drew Furtado, New Bedford Whaling Museum

An enormous whale skeleton hangs over the lobby of the New Bedford Whaling Museum, a visual sign of the institution’s raison d’étre. The whaling and fishing industries take center stage, with permanent exhibits concentrating on the pivotal role they played in the evolution of the South Coast’s history and economy. The museum does a terrific job weaving together the stories of shipbuilders, seafarers, scientists, and artists.

The museum also spotlights the stories of the communities that have made the area home. Lighting the Way: South Coast Women’s Lives, Labors, Loves uses an impressive array of objects and works of art to accentuate the contributions that women have made over the years. Most of the objects come from the museum’s permanent collection, and half a dozen are on loan from contemporary artists. According to museum curator Naomi Slipp, the permanent collection has more than 1,000 objects relating to women, and about 100 are included in the exhibit. She mentioned that, in the past two years, the museum has made more than 25 new acquisitions relating to the region’s women. Slipp noted that selecting, organizing, cleaning, and conserving the objects was a two-year effort.

There’s a lot to take in here. Quilts, posters, paintings, and embroidered samplers adorn the walls; baskets, photographs, letters, scrapbooks, and newspaper clippings fill glass cases. All the handmade objects are made by girls and women who have lived in the cities and towns of Massachusetts’ South Coast — Acushnet, Berkley, Dartmouth, Dighton, Fairhaven, Fall River, Marion, Mattapoisett, New Bedford, Wareham, and Westport.

If an object is not handmade, it is displayed to illuminate the accomplishments of women who have played a key role in shaping the social, cultural, and economic development of the region.

The thesis of the exhibit is that women’s achievements have historically been overlooked and are worthy of our attention. In the introductory text, the curators acknowledge that the museum’s holdings lean toward white upper-class women who have had power, wealth, and social status on their side. The text poses an important question: “Museum priorities have changed significantly since then, but the question remains: How do we curate around absence?”

Maker once known, Louisa Seabury Cushman (1811-1895) and Child, 1837. Photo: courtesy of Drew Furtado, New Bedford Whaling Museum

Interestingly, the work of art that greets visitors as they enter the exhibition is a portrait of a wealthy white woman, wearing a shiny gold dress, holding a young child. The label tells us that the sitter, Louisa Seabury Cushman (1811-1895), lost all of her children at a young age. Throughout the 1800s, childhood mortality affected families of all races and backgrounds. Close to 30 percent of children died before their first birthday, and 46 percent died before their fifth birthday. We are not given this information, and that is a missed opportunity to address a critical issue parents struggled with for many years when childhood diseases were commonplace and vaccines had not been developed. The earliest vaccines weren’t available until sometime between the early and mid-1900s. The prevalence of childhood death must have hit women especially hard.

Despite the preponderance of objects made for and by white women, the exhibit does include photographs of women of color, including handcrafted objects by Wampanoag women, a folkloric dress made by a Portuguese woman, and information about Cape Verdean women. The show would have benefited from supplying more information about these women’s lives and the particular challenges they faced because of their skin color and ethnic background.

A glass case containing several baskets includes two objects made by contemporary Aquinnah Wampanoag women: a basket by Elizabeth James Perry and a deer hide bag by Julia Marden. Unfortunately, there is no text explaining the significance of this work. The Wampanoag Royal Cemetery is located in Lakeville, Massachusetts, not far from New Bedford. Descendants of the Wampanoag Sachem Massasoit lived in the Betty’s Neck area of Lakeville for many years. Although their population has declined considerably over the years, the Wampanoag people continue to thrive in Mashpee and in Aquinnah, on Martha’s Vineyard. The Indigenous tribe still carries on many of its long-standing traditions, including the crafts of beading and basketry.

While I understand the constraints that the museum’s collection placed on what’s in the exhibit, more interpretive texts could have grappled with the question of how to curate around absence. Curating is inevitably a balancing act. Exhibition staff aims for a harmonious blend of visual and textual information; objects should be supported, but not overshadowed, by interpretation. In the case where there were only a few objects to exemplify a minority group, the curators might have provided explanatory text to fill in the gaps.

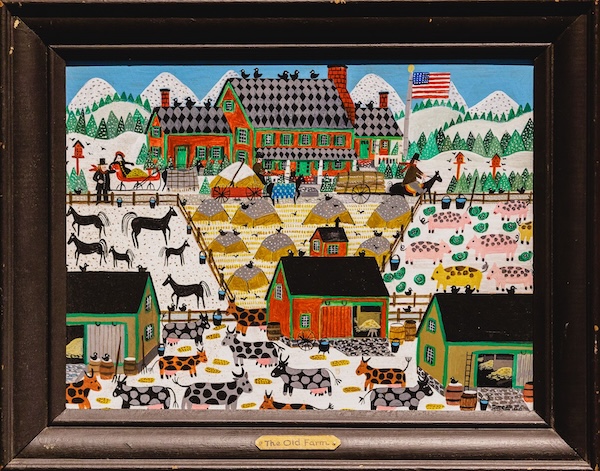

Rosebee (Ceclia Surdut), Farmyard Scene, c. 1990. Photo: courtesy of Drew Furtado, New Bedford Whaling Museum

Despite this imbalance, Lighting the Way is teeming with objects that illuminate stories about the lives and work of the women who made enduring contributions to the region. There are photographs and newspaper clippings about women who have formed charitable groups, led religious institutions, and started nursery schools, mother’s clubs, orphans’ homes, and social service agencies. Their work, whether paid or volunteered, has been essential to the everyday lives of the South Coast community.

There’s a tribute to the New Bedford chapter of Hadassah, founded in 1925. This Jewish women’s organization was formed to offer medical relief to members of the community. In a section devoted to religion, text and photographs underline that women have held positions of leadership in churches and synagogues, starting educational programs, community kitchens, and other social aid initiatives.

In a section focused on social activism, we learn about the women who founded The New Bedford Day Nursery in 1886 to provide care for children whose parents worked in the local mills. The New Bedford Orphan’s Home opened in 1843, and several other local social services agencies were founded in the early 1900s to support families and children living in poverty. The Association for the Relief of Aged Women (ARAW) was created in 1866 to provide financial aid to women who worked out of their homes. This women-run organization is still operating today.

Snow Family Crazy Quilt, c. 1890. Photo: courtesy of Drew Furtado, New Bedford Whaling Museum

In a section on work, a series of black-and-white photographs depict women at various local places of employment. Despite facing lower pay and other obstacles, many women worked — in cotton mills, factories, schools, libraries, and hospitals. By the 1870s, whaling was dying out, and the textile industry was growing. Immigrants from all over were landing in the South Coast region, and many toiled in unregulated factories, putting in 80 hours a week.

In addition to several beautiful quilts made by local women, there are several handmade dresses — an exquisite mourning dress from 1900, a day dress from the 1830s, a maternity dress from 1780, a wedding gown from the 1870s, and a Portuguese folkloric outfit from 1950. These stunning examples speak to a time when girls learned how to sew, embroider, knit, quilt, and weave, and made clothing and domestic items for friends and family.

Another part of the exhibit is organized around the artwork of South Coast women who were fortunate enough to attend art school. I was interested to learn that the Swain School of Design was founded in New Bedford in 1881, and the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) was started by a group of women in 1876. There are several examples here of artwork made by women who attended these schools.

A caution: because of the large number of objects included in the exhibition, there are labeling issues. At times it is difficult to match up a label with a particular object or work of art. In a few cases, there are no labels at all. Despite these small glitches, the exhibition offers much to appreciate about South Coast women, whose lives and accomplishments have played a crucial role in shaping the region.

Lauren Kaufmann has worked in the museum field for the past 14 years and has curated a number of exhibitions. She served as guest curator for Moving Water: From Ancient Innovations to Modern Challenges, currently on view at the Metropolitan Waterworks Museum in Boston.

Tagged: "Lighting the Way -- South Coast Women’s Lives, Labors, Love

What a beautiful and thoughtful review of of the New Bedford Whaling Museum current exhibit, “Lighting the Way”. It is very exciting that this museum has acknowledged the dearth of exhibited contributions of women during this period, and attempts to shed light on them. Hopefully, it will serve as an inspiration to dig deeper and for other museums to join this effort. Despite the limited interpretive text of indigenous work, I will go out of my way to visit this exhibit.