Book Review: Moon Unit’s “Earth to Moon” –A New Age Quest for Healing

By Trevor Fairbrother

Moon Unit devotes less than a quarter of her book to the three decades since her father’s death. Despite his failings as a parent, she wants to respect Frank Zappa’s stature as an artist.

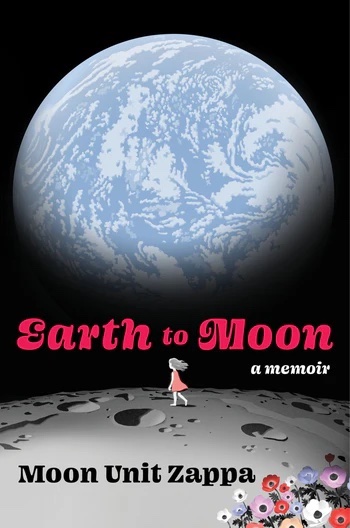

Book jacket illustration by Jun Cen, a New York–based artist born in China.

Earth to Moon: A Memoir by Moon Unit Zappa. Dey St., an imprint of William Morrow, 368 pages, $23.99.

Did Gail and Frank Zappa expect attention when they named their daughter Moon Unit? Clue: their next three kids were Dweezil, Ahmet Emuuka Rodan, and Diva. In this book the eldest child displays her wounds. Moon Zappa, a La-La Land “it girl” in the 1980s, is now in her mid-50s. Her father passed in 1993, her mother in 2015. On the last page she describes herself as “a writer, yogi, mom, artist, nature lover, podcaster, and tea baroness.” Guardian journalist Nick Duerden calls Earth to Moon “an unconscionably entertaining read” because the funny, keen-witted author calls on nimble prose to tackle her dispiriting subject matter.

Frank Zappa, a singular musical genius, married Adelaide Gail Sloatman, a hipster businesswoman, in New York on September 21, 1967. Their daughter was born a week later. Frank and his Los Angeles–based rock band, The Mothers of Invention, had recently developed a raunchy agitprop pageant now hailed as a milestone. During their five-month stint in Greenwich Village, Frank dreamed of staging “a Broadway musical science fiction horror story based on the Lenny Bruce trials,” and conducting “an 84-piece rock & roll orchestra on the stage of Carnegie Hall.” (Hit Parader, June, 1967).

In August 1968 the Zappas purchased a house in the Hollywood Hills above Laurel Canyon Boulevard. The property evolved into a compound with guest cottages, swimming pool, tennis court, and recording studio. Earth to Moon parses the meanness, narcissism, and emotional neglect Moon Zappa encountered growing up there. To see people naked and hear her parents’ lovemaking was routine. She is clear-eyed about her father’s addiction to groupies, on the road and at home. “It’s only fucking,” Frank would tell Gail.

Moon’s parents were lapsed Catholics who self-identified as “pagan absurdists.” Her mother was happy to show her daughter her collection of old prayer cards even as she endorsed the occult. She forbade Moon to go to church but allowed her to watch The Flying Nun on TV. The Zappa household attracted freeloaders — “a diverse array of horny dreamers, oddballs, misfits, and sycophants.” Inside the bubble of a “pharaoh lifestyle” Frank ruled and Gail played cop. Moon’s comments about her mother’s authoritarian rampages are probably not exaggerated. Background research for this review led me to an interview in which Frank brags, “[Gail’s] a mean little sucker. She’s an excellent boss’s wife. Everybody knows that Gail is the boss’s wife.”

There were, of course, pockets of love. At five Moon received the first of many elegant blank books to encourage her to have fun drawing and “journaling.” They helped when Frank was away on tour during countless long stretches. At the age of 10 she was confused by her parents’ guidance. They encouraged her to “say anything or think anything or do anything,” but there were also admonitions. For example, Frank said “Never do anything stupid unless you’re gonna get paid for it.” This stumped Moon: “I can never tell what he and Gail think is stupid until after I do it, so I definitely don’t want anyone to know that I secretly draw penises in my journal and wonder about them.”

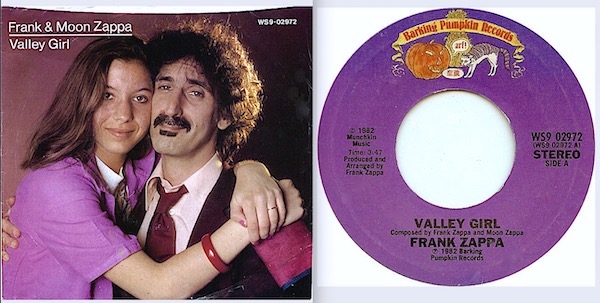

7″ single version of “Valley Girl,” 1982.

At 13, Moon yearned for Frank’s attention. His waking hours were spent in the off-limits home studio, so she got formal and wrote a letter. It was an offer to sing with him, but also broached doing impersonations of surfers and airhead girls who love to shop. Two years later, Frank asked her to help with “Valley Girl,” a song that satirized a certain demographic in the San Fernando Valley. Mimicking an effete affluent girl, she jabbered about repellent adults, cat boxes, and dirty dishes: “It’s like really nauseating / Like barf me out / Gag me with a spoon / Gross.”

Zappa included their collaboration on his album Ship Arriving Too Late to Save a Drowning Witch, released in May 1982. He held the copyright for everything “except the monologue in ‘Valley Girl,’ which was improvised by MOON.” Heavy radio play led him to release the song as a 7-inch single, now crediting Moon as co-writer. Then came the pop culture avalanche: a father-daughter guest spot on Late Night with David Letterman; a lip-synching TV appearance with the dancers on Solid Gold; and a cameo in one of Frank’s shows in Germany.

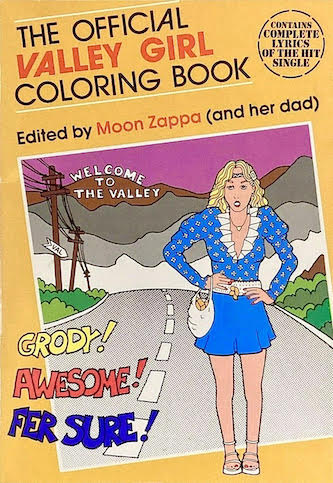

Coloring book illustrated by Roger Burrows, published by Price/Stern/Sloan, Los Angeles, 1982

“Valley Girl” made Moon an entertainment industry starlet. Frank resented the fact that the public enjoyed it as a happy, silly novelty song: his credo was to confront and make fun of anything crass, phony, or exploitative. He was ready, nonetheless, to profit from licensed “Valley Girl” merchandise that included a coloring book. Meanwhile, his wife became jealous. Moon recalls Gail saying on several occasions, “I am the only reason your father gave you credit on the album and the only reason you are getting any money. Frank didn’t want to give you any writing or performing credit.” Gail also claimed that Moon’s slot in the German concert was a way to max out business expenses on tax returns.

Moon devotes less than a quarter of her book to the three decades since Frank’s death. Despite his failings as a parent, she wants to respect his stature as an artist. She also needs to understand why Gail grew more selfish and dysfunctional after she became the head of the family. Moon stayed busy: she acted, hosted music shows on TV, did stand-up comedy, and wrote a novel (America the Beautiful, 2001, not mentioned in Earth to Moon). In 2002 she married rock musician Paul Doucette; their daughter was born in 2004; their divorce occurred in 2014. Her husband saw through Gail’s racket, and Moon trusted and loved him more after he compassionately professed, “Your mom is a very sad and insecure woman.”

Gail’s death in October 2015 introduces the last circle of hell described by Moon. The head of the Zappa Family Trust used her will to throw a curveball. She named her third child, Ahmet, the trustee. Both Ahmet and Diva received shares of 30 percent, while Dweezil and Moon received 20 percent each. Moon construed this as Gail’s final punishment of the two kids who had occasionally questioned her administrative decisions. The trust was millions of dollars in debt when she died, and no distributions could be made until it became profitable. In 2016 Ahmet oversaw the sale of the family compound and the consignment of furnishings and memorabilia to Julien’s Auctions. Apparently, it took a few years to reconcile all the siblings’ legal differences.

In anticipation of the release of Earth to Moon, Geoff Edgers profiled the Zappa clan for the Washington Post. He visited L.A., hoping to sit down with all four siblings, but Dweezil refused to join a meeting that included his brother. Clearly the anger ignited by Gail’s will still lingers. Moon, nonetheless, gives her book a happy-ish ending, wishing for loving sibling coexistence. Her whimsical quest for reclamation is encapsulated by Jun Cen’s lovely jacket illustration — a barefoot waif girl trekking past a clump of anemones in a gray moonscape.

Screenshot detail from moonunit.com, accessed Sept. 15, 2024

The author rarely steps back from her narrative. What are her thoughts on the earlier books of two Hollywood daughters — Christina Crawford and Tatum O’Neal — who had lousy parents? She does mention one aha moment involving a comment that Andy Warhol made about her father in June, 1983. The effect is very poignant. The men were chatting after recording an interview in Manhattan. Warhol said he thought Moon was “great.” Frank replied, “Listen, I created her. I invented her.” Warhol was appalled by a father who took no pleasure in the fact that his daughter was “so smart.” This story first appeared in print in 1989 in The Andy Warhol Diaries. Did Moon read Warhol Diaries when her father was still alive? Has she discussed it with any family members? She doesn’t say, but makes it clear that Warhol’s words in her defense struck her as “a tiny light in the dark” and validated her healing New Age quest to re-parent her younger self.

To read more about Frank Zappa on the Arts Fuse, check out Chelsea Spear’s 2021 book review and my 2024 essay.

© 2024

Trevor Fairbrother is a curator and writer. In 2012 he wrote Making a Presence: F. Holland Day in Artistic Photography in conjunction with an exhibition of the same name at the Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover, MA.