Book Review: “The Letters of Seamus Heaney” – The Burden of Good Fortune

By Leigh Rastivo

In his letters, Irish poet Seamus Heaney’s tone, and the expanse of his openness, varies according to the addressee — but his approach to all is inevitably marked by seriousness and elegance.

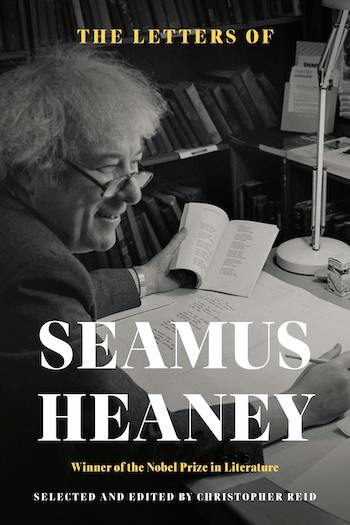

The Letters of Seamus Heaney, selected and edited by Christopher Reid. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 820 pages, $45.

The Letters of Seamus Heaney, selected and edited by Christopher Reid, is a hefty tome, not just physically (at 800+ pages), but also topically. This heft is to be expected. The beloved Irish poet was a Nobel Laureate, a translator, a lecturer, Harvard University’s Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory, the Oxford University Professor of Poetry, a friend to many, and a copious writer who came of age when letters were a primary form of communication. Of course, Heaney’s “epistolary output” (as Reid calls it) is bountiful and contains the reflective discourse of a literary giant whose time was in demand continuously. And yet, this oversized book is not cumbersome or even somber — in fact, it is quite the opposite. After imbibing its many pages, one after the other, hundreds on hundreds, a well-nourished reader will leave the feast feeling the weight of Heaney’s engagement in the world, but also with a sense of lightness, derived from the candor and warmth that resonated from him even on his most hectic or frustrating day.

This is in part due to masterful editorial choices. To his credit, Reid does not add unnecessarily to the weight of the volume. Despite considering countless letters, he “cut back severely to make a book of publishable proportions.” For example, Reid does not start this chronological presentation with Heaney’s childhood missives. Instead, Reid begins when Heaney is 25 and just emerging as a professional poet, with a letter to his lifelong friend Seamus Deane, written while Heaney waited to hear if his first collection would be published.

The fact that Reid was not permitted to include any correspondence with Heaney’s immediate family members — he informs us their privacy was “inviolable” — also helps cut down on excess, ensuring that the collection stands as a curated presentation of the public poet without the distraction of what Heaney called the “shock of intrusion.” Still, what may be the largest contributor to the buoyancy of the volume is Reid’s measured editorial presence. Rather than interrupting the flow of individual letters by fixing errors, Reid provides a Notes on the Text section upfront, defining what has been corrected for the sake of establishing a “clean easy text” shorn of typos, dropped words, forgotten punctuation, etc. After that, Reid steps deftly to the side, encouraging the reader to dive into the substance. Each letter is allowed to stand alone, with brisk, helpful footnotes inserted when the content might raise questions. Reid also provides lean introductory summaries before each year’s batch of letters. Thus, readers can experience the alluring insider’s view that the epistolary form promises, while also being subtlety schooled on obscurities that might be otherwise distracting. The result is a book that is accessible, whether one knows Heaney’s work or not.

In his Introduction, Reid underlines the juxtaposition of weight with lightness, observing that if the book has a theme “… it is Heaney’s obligation to duty,” while also noting the presence of Heaney’s lesser known “off duty high-spirits” and “the pleasure he unmistakably takes” in making connections with others. This framing suggests there will be a back and forth of work and play, perhaps an either-or set up: either a lighthearted off-duty note to a friend or serious literary and academic business. But The Letters of Seamus Heaney is not a balancing act — there’s no see-sawing equilibrium. The seriousness and effervescence overlap, coexisting aspects of Heaney’s life that are evident in nearly every letter.

The overwhelming pressure of literary celebrity is a prevailing theme throughout. Such pressure is to be expected, and it must be ignored. But Heaney had trouble with the latter: his steadfast commitment to his unending “To Do” list (whether he was technically at work or play) was a strenuously self-imposed standard. Despite his occasional frustration, Heaney’s “tenacious sense of duty” was inseparable from the satisfaction that came from reaching out to others. In a candid letter to Barrie Cooke, Heaney wrote about his need to quite literally answer all the mail:

In the last two days I have written thirty-two letters … all of them a weight that was lying on my mind even as the accursed envelopes lay week by week on my desk. The trouble is, I have about thirty-two more to write: I could ignore them but if I do the sense of worthlessness and hauntedness grows in me … fuck it, I’m going to get rid of them before I board the plane on Thursday.

Heaney also lamented holidays; he was not cut out for taking time off. He told Thomas Flanagan: “I am not altogether made [for this] … thinking of the mail piling up at home and the faxes.… A feeling that sunlight and silence and free time on a Tuesday morning on a Greek island is an affront to the workers of the world.”

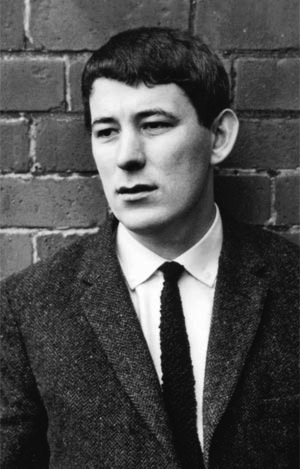

Seamus Heaney, around the time of his first book, Death of a Naturalist, 1966. Photo: Wiki Common

The inundated Heaney often began (or ended) a letter apologizing for its lateness, compensating with warmth and insight. He provided friends, colleagues, and fledgling poets with specific and honest criticism and earnest encouragement. In fact, his support was often beautifully effusive. This, to Ted Hughes: “I’ve read Gaudete twice and was deeply pleasured by it each time.… I feel the shape of the story was a plough that got deep into the ground of your gift and opened it marvelously. The abundance of the thing from line to line is a blessing…” This to Stanisław Barańczak (speaking of Animal Ferocity: From the Notes of a Discouraged Zoologist): “What energy and hack-saw edge and intelligence. The variety is wonderful, but what makes it extraordinary is the intensity of each excellence.”

Reid himself received extravagant praise from Heaney (perhaps a foreshadowing) for his editing of The Letters of Ted Hughes: “I am atremble and in awe … the intensity and abundance have tilted scales and changed perspectives.… the book doesn’t just complement the poems, it gets out (as Frost might say) by getting through, through into a new order or ether of art-knowledge.”

Likewise, Heaney’s letters to his editor Charles Monteith, although more professional, were also somewhat unguarded, with the poet sharing personal details freely, even in the early days of the relationship:

This week, I am convinced, has been the most eventful in my life — you accepted my book as I was in the process of buying a house (we’re being married in August) and these two unparalleled events occurred in the middle of a hectic period of examination marking…. To-day I came to the opening of Yeats’s Tower in Galway and at last have got round to the solitary realization of my incredible good fortune.

This early letter sums up a multifaceted existence. Heaney was a man of letters with a family life; always engaged, he felt over-busy and lucky at once — fortunate but burdened. He was alert to his responsibilities throughout his lifetime. This start-to-finish openness is even more remarkable given that Heaney became concerned that his letters might someday be collected: “Christ, now that Larkin’s letters are out and Longley’s are in archives, I’m beginning to panic about putting down a line!” He was also troubled by the prospect of unauthorized biographies and even had misgivings about the comprehensive interview volume Stepping Stones, on which he collaborated with Dennis O’Driscoll. In a 2009 letter to the American critic and essayist Sven Birkerts, Heaney admitted to “big doubts about the wisdom of having committed Stepping Stones.… the fact that I had cadenced myself towards a conclusion in the last chapter of that book … felt a lot like a ‘summing up’ exercise — all combined to induce a not so subliminal sense of an end.”

The letters traverse half a century and touch on a wide range of topics, from Heaney’s time in Belfast to his move to Wicklow, his teaching positions in the US, and onward to the Nobel Prize and public eminence. Heaney writes to a varied swath of friends, colleagues, editors, publishers, and fellow writers. There are letters that go into Heaney’s family life (his marriage to Marie Devlin and the birth and upbringing of his three children Michael, Christopher, and Catherine); his thoughts on poetic inspiration (including the Iron Age burial rituals meditated on in The Bog People, which became the poet’s metaphor for the Troubles in Northern Ireland); and his musings on less focused days (“I sit here with a third child, no job, no real idea of where I am going or what I want to do.”). The variety creates a multifaceted portrait of Heaney that is both overarching and nuanced. Again — heavy but light.

Predictably, Heaney also addresses politics. For example, writing to Northern Irish writer Brendan Hamill in 1973, Heaney shared his thoughts about the role of the poet in wartime: “Perhaps the poetry hasn’t been personal enough. Certainly … there should be a voice of freedom issuing from the poets. But the voice can’t be summoned — a poem is a different utterance from a newspaper leader.” Heaney’s tone, and the expanse of his openness, vary according to the addressee — but his approach to all is inevitably marked by seriousness and elegance.

This long, thoughtful book ends abruptly, with a small act of defiance. Breaking his rule of “no family correspondence,” Reid caps the correspondence with Heaney’s famous final message to his wife. The poet Heaney, who had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature “for works of lyrical beauty and ethical depth, which exalt everyday miracles and the living past,” sent a text just before he died on a Dublin operating table in August 2013: “Noli timere” (Latin for “Do not be afraid”). How apt: the grace in that heaviness, the utter concern for the recipient.

Leigh Rastivo is a fiction writer, reviewer, and essayist. Her shorter fiction has been published or is forthcoming in several journals, including the MicroLit Almanac and L’Esprit Literary Review, and she recently attended the Under the Volcano international residency to workshop two novels.