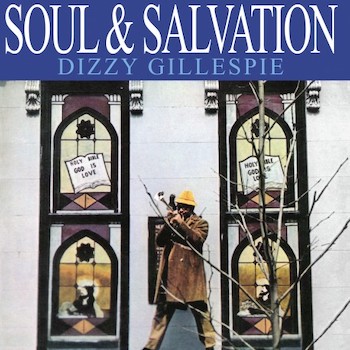

Jazz Album Review: Dizzy Gillespie’s “Soul & Salvation” — The Spirit Is Cheesy But Willing

By Allen Michie

Soul & Salvation is a short album, and you’ll be sorry when it’s over. It’s hardly an essential album in Dizzy Gillespie’s long discography, but you won’t regret giving it a listen.

Dizzy Gillespie – Soul & Salvation (Liberation Hall)

Even die-hard Dizzy Gillespie fans can be forgiven for not having heard of this album. Originally released in 1969 on Tribute Records, Soul & Salvation (reissued in 1970 as Souled Out) has been out of print for 15 years and unavailable on vinyl for almost 50 years. Liberation Hall Records has just released it on CD, LP, and the streaming services, making it available to the grandchildren of those few who heard it in 1969.

Even die-hard Dizzy Gillespie fans can be forgiven for not having heard of this album. Originally released in 1969 on Tribute Records, Soul & Salvation (reissued in 1970 as Souled Out) has been out of print for 15 years and unavailable on vinyl for almost 50 years. Liberation Hall Records has just released it on CD, LP, and the streaming services, making it available to the grandchildren of those few who heard it in 1969.

It was not a hit. It was Gillespie’s attempt to participate in (cash in on?) the soul jazz trend of the late ’60s. Cannonball Adderley, Ramsey Lewis, Hugh Masekela, Les McCann, and others had all had hits in the genre, so why not Dizzy? But this style of soul jazz had already passed its heyday: 1969 was the year Bitches Brew came out. There was only one trumpeter in the jazz/rock world, and it turned out to be one of Gillespie’s former protégés. Fusion was evolving in very different directions. Gillespie was just now getting on board — with something that would have been groovy in 1966.

Gillespie does not mention the album in his memoir To Be or Not to Bop. It’s not included in his selected discography either. No mention anywhere on Wikipedia. It’s also omitted in Alyn Shipton’s standard biography, Groovin’ High: The Life of Dizzy Gillespie. In fact, Shipton only covers the late ’60s as a time when Gillespie was stuck in a musical rut; he was bored, keeping to the same set list, and enduring gigs in small clubs far beneath his stature in the jazz pantheon. He took to drinking heavily, although he stopped around 1969, after finding the Baha’i faith. Soul & Salvation wasn’t part of any steady R&B trend for Gillespie — there was nothing leading up to it and nothing immediately following it. For some listeners, Soul & Salvation will qualify as a genuine rara avis of a forgotten session from a major artist. For others, it will be just a curiosity or a blip.

Ed Bland wrote all the compositions and arrangements, and a 16-piece band was put together including Joe Newman, James Moody, Benny Powell, Joe Farrell, and Cornell Dupree. Sure, it’s slumming for musicians of this caliber. They play this lightweight stuff effortlessly. But you can tell when musicians are enjoying their holiday.

The cheese content varies. Some of it, like “Pot Licka,” carries the force of real gospel music, thanks in large part to the uncredited female vocalists who are not there to mess around. Other tracks, like “Blue Cuchifrito,” are more obviously slicing the cheese thick and serving it on a cracker for the same DJs who made Herb Alpert’s “Taste of Honey” and Hugh Masekela’s “Grazing in the Grass” instrumental trumpet hits. That fat, thumpy electric bass is very late ’60s. But just because it’s cheesy doesn’t mean it isn’t awesome (check out the busy bass on “Chicken Giblets”).

In other words, the album is worth taking seriously, and not just because it’s a discographical oddity, but also because it’s from Dizzy Gillespie, one of the greatest trumpeters to ever touch the instrument. Straight-up bebop licks are few and far between. Gillespie plays some of bop’s famous flat fives and nines, but that’s not the emphasis here. Gillespie draws on his signature conflation of the blues scale with the bebop scale, and the gospel inspiration here allows him to indulge his fondness for vocal-sounding half-valves and sudden upward shouts. Many of his standard licks and patterns, which will be familiar to listeners of his lightly funky live sets well into the ’80s, mostly work well in this soulful R&B context.

James Moody opens the first track, “Stomped and Wasted,” with an assertive blues declaration, and the format frees him to explore some blurs, growls, and vocal-style phrasing that he usually doesn’t do with his straight-ahead jazz. Gillespie’s solo screams and shouts with shorter phrases than he would usually do, about the length of a singer’s breath. It’s a happy, spirited sound, with an organ popping away in the background to give the track a gospel touch.

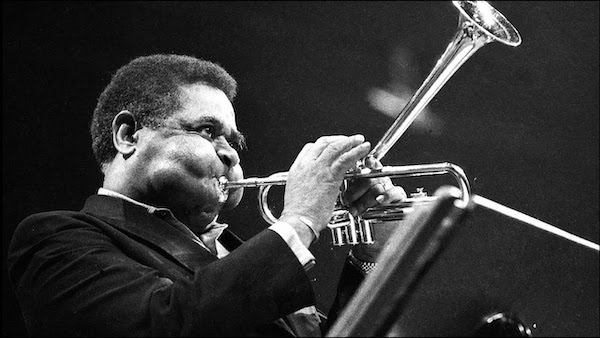

Dizzy Gillespie performing in the ’60s. Photo: Wiki Common

The band goes all-in with the gospel on “Pot Licka.” Gillespie is clearly inspired by the utterly liberated gospel singers, perhaps relieved to spend the day playing something other than “Manteca” and “A Night in Tunisia” for a change. Similarly, on “Turnip Tops,” the gospel singers goose the alto sax soloist and Gillespie into some dramatic solos. It’s a soulful waltz in 6/8 time, like something Ray Charles might play.

“Chicken Giblets” is a kind of soul march, and Gillespie’s solo indulges in more of those boppish intervals (the “Chinese sound” that Louis Armstrong complained about). Gillespie trades licks with Joe Newman, a traditional jazz trumpet player who is fully engaged here and apparently enjoying the musical holiday. Ditto for Moody and his fun, short solo. Newman is back, this time with plunger mute (probably why he was chosen for this gig), on “Rutabaga Pie,” playing along with the trombone riffs for some great greasy blues. The singers add the fatback, and Gillespie balances it out with some off-kilter harmonics. The groove likely owes something to Herbie Hancock’s 1962 soul jazz hit, “Watermelon Man.”

“Turkey Fan” is a feature for the tenor player, probably Joe Farrell, playing jazz over this light rock beat. Dupree shows his great rhythm guitar playing, here and throughout. Gillespie plays some of the same licks he plays on the other tracks, but who cares.

Then there’s the processed American cheese. “Blue Cuchifrito” is flower-power elevator music, complete with cheerful flutes playing the simple melody. Gillespie does what he can with it, pro that he is, but he’s going through the motions. “The Fly Fox” has that cool lounge sound, complete with vibes, to play on your vintage stereo console in your mid-century furnished den with a teal sofa. Gillespie plays muted trumpet in unison with the vibes, and you can almost hear those martinis getting mixed. It soon gets a degree funkier with Gillespie’s hot solo and Dupree’s rhythm guitar.

But indulge me for zeroing in for a moment. It’s worth remembering that, even in an unchallenging cheeseball setting, we’re still dealing with one of the most sophisticated and original harmonic minds in the history of jazz. Toward the end of “The Fly Fox,” from 3:17-3:21, Gillespie tosses off a lick that no garden-variety R&B musician would ever think of — and it works, without being pretentious or out of place. He ascends up in the Phrygian mode starting on G, then descends with a pentatonic scale starting on F that outlines a D-flat chord. In other words, he plays in D natural on the way up, and in D flat on the way down. This gives the first half of the lick a brighter sound, and the second half a darker sound. That D-natural and the D-flat are the only two notes that aren’t shared between the two scales. It’s pure genius, and it sounds like no one else but Gillespie, no matter whatever else is (or isn’t) going on with the rhythms and arrangements in the background.

Soul & Salvation is a short album, and you’ll be sorry when it’s over. It’s hardly an essential album in Dizzy’s long discography, but you won’t regret giving it a listen. It’s a surprise release with many smaller surprises waiting inside.

P.S. I was going to combine this review with a fresh listen to Gillespie’s other forgotten commercial fusion album, Closer to the Source, from the peak smooth jazz year of 1984. But I couldn’t make it past the third track. It’s awful. In a 1980 interview, Gillespie confessed “my plan for the future is to make me a disco album. I figure the money is there, it’s nothing that I haven’t heard before. I can do it, so why not do it and get the money?” Simon Adams wrote in Jazz Journal International that Closer to the Source was “the most embarrassing record of almost all time.” Shipton describes it as “the lowest point of Dizzy’s ’80s career. Despite the presence of Branford Marsalis and Stevie Wonder, it is a poor production, with Dizzy playing well below his best, and the kind of aberration that most musicians make once or twice in their working lives.”

(Many thanks to music theorist Anna Brock for assistance with “The Fly Fox” analysis.)

Allen Michie works in higher education administration in Austin, Texas. You can find an archive of his essays and reviews at allenmichie.medium.com.

I enjoyed your descriptions of the tunes. I have an 1967 Dizzy LP — The Melody Lingers On that shares some of the same marginally interesting music (“Winchester Cathedral”, “Cherish”…). One other thing — Joe Newman was a flat out swing player — I wouldn’t call him traditional.