Jazz Feature: Saxophonist Gregory Groover Jr. — At the Intersection of Spirituals and Jazz

By Martin B. Copenhaver

Saxophonist Gregory Groover Jr, was not initially drawn to spirituals. In fact, as a young person, he found them frightening.

Saxophonist Gregory Groover, Jr. — H was not initially drawn to spirituals. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

Still early in his career, Boston-based saxophone player and composer Gregory Groover, Jr. has taken up artistic residence at the largely overlooked intersection of jazz and spirituals. In two memorable albums, Negro Spiritual Songbook, vol. 1 & 2, Groover interpreted traditional spirituals, the music of enslaved African Americans, in ways that honor the songs’ history and, at the same time, explores them anew through jazz.

In one respect, it is not surprising that Groover would focus on spirituals. He grew up in the church. His father, Gregory Groover Sr., is the eminent pastor of Charles Street African Methodist Episcopal Church in Roxbury (he is also a friend of mine). In worship each Sunday, the younger Groover would hear music from various genres, including gospel, praise music, choral ensembles, as well as spirituals. What he did not hear was jazz.

Groover was not initially drawn to spirituals. In fact, as a young person, he found them frightening. Their themes were dark, reflecting the anguish of slavery. When the spiritual “Wade in the Water” was sung during a baptism, the lights were lowered to reflect darkness, as well. Most often, the spirituals would be sung a cappella in a minor key. When the spirituals were performed, the young Groover knew something serious was going on. There was a gravity, a weight, to the music. This was something different from the celebratory gospel music that also had a home in the worship of his church.

Groover loves an eclectic mix of musical genres. Not many people would name both John Meyer and John Coltrane as influences. He attributes the variety of his musical tastes to his father who, while driving around Boston, would play a diverse mix of music.

When he took up the saxophone, Groover began to play in church. At about the same time, he fell in love with jazz. For a time, he lived in two musical worlds — the music of the church and jazz — and the two did not meet. Then one day, Groover declared to himself: “I am going to try something from my world [of jazz] and I’m going to take this spiritual and try to re-arrange it in a way that I want to play it.”

Groover explained his approach: “I respect the melody of the song. I didn’t want to change or alter it in any way, but I also wanted to have the liberty of presenting how I would like the spirituals to be heard now. I wanted it to be accessible to anyone who is listening today.”

The result, to this listener, is nothing short of thrilling. Commenting on Groover’s spirituals project, Walter Smith III, chair of the Woodwinds Department at Berklee, observes, “Taking a source material that is really close to your heart — that is the starting point of any great project.”

As Groover moved into the second volume of his Negro Spiritual Songbook he did not seek to depart further from his source material. Instead, he endeavored to become closer, to stay truer to the spirituals he was interpreting: “I think I’ve proven that I can arrange it and make it hip and make it sound like I would want spirituals to sound if I were writing them today. Okay, that’s great, but how do I get close to the original sentiments expressed in the music?”

Of course, creative innovation remains an essential ingredient in his interpretations of spirituals in the second volume. For instance, one expects to hear “Every Time I Feel the Spirit” played up tempo, as is the case with Groover’s version. But, later in the cut, he adds a rhythmic twist reminiscent of Sonny Rollins classic, “St. Thomas.”

His interpretation of “My Lord What a Morning” makes it even clearer that we are in new territory. This spiritual is usually offered as a meditation, and that is reflected in Groover’s initial go-rounds with the melody. But then the tempo shifts and the mood turns joyous; it is as if Groover is thrilled to see the promise of a new morning and wants to share his enthusiasm with the listener.

In other songs, Groover experiments with different meters. For example, “Go Down Moses,” like most spirituals, traditionally is set in 4/4 time; Groover sets it in 9/4 time, a meter more conducive to jazz. Given the theme of the spiritual, which is a plea for freedom, it seems fitting that this meter accommodates a freer form of musical expression.

Then there are the ways in which Groover’s approach pays homage to the origins of a spiritual and then honors it further by putting it a new setting. His haunting version of “Oh Freedom” captures the mournful mood of the spiritual (“And before I’d be a slave, I’d be buried in my grave”). In Groover’s version, however, there is no choir. He is no longer joined by his fellow band members. He plays without accompaniment, and that underscores the loneliness of the experience. There is no place to hide his sorrow and, as a musician playing solo, there is no place to hide, period. Gratefully, Groover is more than equal to the challenge. His rendition is haunting.

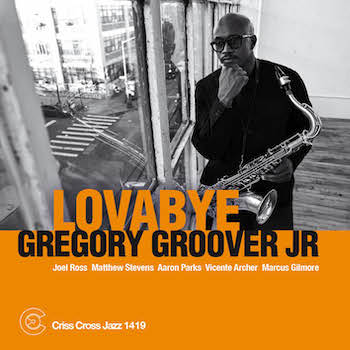

Groover’s work is not limited to offering jazz versions of spirituals. On April 26 he released an album of original music, Lovabye (on the Criss Cross Jazz label). He introduced the new album on May 3 at two sold-out performances at Cambridge’s Regattabar to a highly pleased audience. His sextet on the album — and in the show — is made up of prominent New York-based musicians. Groover once wondered aloud if he could ever hope to play with some of his musical heroes. A mentor responded, “Why don’t you ask them? You have the material.” So, he asked and, to a person, they agreed to join him, which in itself says something about how his musicianship is regarded.

Groover’s work is not limited to offering jazz versions of spirituals. On April 26 he released an album of original music, Lovabye (on the Criss Cross Jazz label). He introduced the new album on May 3 at two sold-out performances at Cambridge’s Regattabar to a highly pleased audience. His sextet on the album — and in the show — is made up of prominent New York-based musicians. Groover once wondered aloud if he could ever hope to play with some of his musical heroes. A mentor responded, “Why don’t you ask them? You have the material.” So, he asked and, to a person, they agreed to join him, which in itself says something about how his musicianship is regarded.

Reflecting on Groover’s work as a whole, Walter Smith observed, “[Groover’s] goal is not for the music to hit you in the head in an intellectual way. Rather, the goal is the feeling behind it, the emotive part of it. He has that at the forefront of his playing. It is the point of the whole thing. And he is very good at doing that.”

In addition to performing his original work, and his day job as Assistant Chair of the Ensemble Department at Berklee, Groover will continue to play his interpretations of the spirituals, both at church and at performances in clubs and concert halls.

Smith sees Groover’s work with the spirituals as a long-term endeavor: “The interesting part of his project is that it will never get old. He can continue to explore that side of his music throughout his whole career. He could record ten more spiritual albums, in addition to the other things he will do with his original music or other types of music. It is one of those projects that always makes sense.”

Martin B. Copenhaver, the author of nine books, lives in Cambridge and Woodstock, Vermont.