Visual Arts Review: Si Lewen’s “Parade” Resurrected — Just in Time for a New War

By David D’Arcy

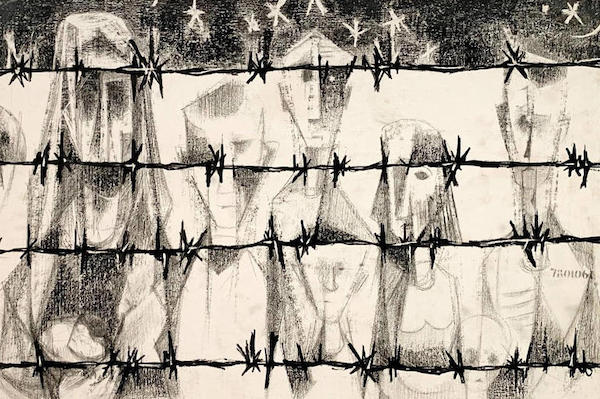

Parade’s power does not lie in its mystery or its revelations of combat. The work, as artist Si Lewen lays it out, surveys the absurd pomp and horror of war.

An image from Parade, 1950. Photo: courtesy of James Cohan Gallery

Polish born painter Si Lewen (1918-2016) could draw with a delicate touch, but he could also slam figures onto paper with a thud that, decades later, makes you think you can hear or smell them. A wildly productive artist, Lewen wasn’t stuck in a particular style: he borrowed relentlessly and unapologetically from whatever he saw. Drawings from his 1950 series Parade are being shown in New York for the first time in 70 years at the James Cohan Gallery (through April 27, with no charge to visit). They have particular relevance now because, taking the form of an early graphic novel, they view war and militarism with a marvelously jaundiced eye. There is no need for captions: what words do you need when an army horse in dress regalia makes its own decorative droppings part of a grand spectacle?

The images were exhibited at the Menil Collection in Houston last year. Those who can’t make the New York show should take a look at Si Lewen’s Parade: An Artist’s Odyssey (Abrams Comicarts), edited and with an introduction by Art Spiegelman. The volume presents Lewen’s drawings along with an overview, biographical information, and a fellow artist’s appreciation.

Parade is a suite of 63 images in black and white that present the grit of war with the hurtling momentum of a music hall performance and the irreverent punch of — God forbid — comics. The latter element accounts, at least in part, for Spiegelman’s attraction to the work. Of course, let’s not rule out ancestor worship: a visual storyteller’s reverence for an earlier master.

Si Lewen, Self-Portrait, 1984. Photo: courtesy of James Cohan Gallery

We enter the work as a parade of men in uniform (with a decorated defecating horse) marches across a frame. In other scenes children swoon in awe at what they see — the kids are eventually led away. Then come armed figures in formation, and war itself — abstract lines and patterns scratched on the page, explosions, then images of destruction and boxes of bodies carried off. Is abstraction part of the mix because the horrors that Lewen and his World War II generation witnessed are too harsh to identify? Soon enough, along with scenes of the ravages of war, come images of soliderly seduction, pomp, and noise.

Parade‘s power does not lie in its mystery or its revelations of combat. The work, as artist Si Lewen lays it out, surveys the absurd pomp and horror of war. His images of mortality feel as explosive now as they were seven decades ago. Along with depictions of tenderness and mourning, there are frames here that have the emotional instantaneity of billboards. This visceral force — cinematic in its use of multiple perspectives — draws on the power of comics with a seriousness that takes the viewer beyond the limits of commercial melodrama.

The artist, an atheist descendant of rabbis, was born in Lublin, Poland in 1918, right after the armistice that ended World War I. Soon his family fled from the pogroms to Germany, from which they fled again as Hitler came to power, finally reaching the United States. There Lewen learned that there was plenty of antisemitism to go around. He was beaten in a rowboat by a Jew-hating cop in Central Park. Later he painted a peaceful scene of the pond where the attack happened. With Lewen, there are almost as many compelling stories as there are images.

The talented kid who loved museums enlisted in the US Army. He found himself in the Ritchie Boys, a unit of German-speaking GIs, many refugee Jews among them. After landing in Normandy, Lewen’s job was to stand in a truck-bed with a bullhorn calling for German soldiers to surrender. He quickly saw the dark side of revenge when Free French soldiers, fighting alongside the Allies, executed a frightened German private whom Lewen had caught hiding in civilian clothes. The artist was appalled when the French refused to spare him. (Spiegelman concluded that Lewen was the world’s most God-fearing atheist.)

A selection of Si Lewen’s Ghosts. Photo: courtesy of James Cohan Gallery

In Germany, Lewen became even more appalled when he and others from his unit reached the Buchenwald concentration camp near Weimar and they saw piles of Jewish corpses. In his narrative about his efforts to find an audience for Lewen’s work, Spiegelman points to the artist’s unpublished memoir, where Lewen recalled “my insides were one wrenching mess. I knew that I was finished as a soldier, seeing the world for what, I thought, it was: a slaughterhouse, a bordello, and an insane asylum, run by butchers, pimps, and madmen. . . . A hospital ship brought me back to America, and half a year later I was discharged — ‘as good as new,’ one of the doctors said. I was not so sure.”

Good as new? Lewen was right to have had doubts, but he resumed his art studies, and would teach art (and sell what he could) for most of his life. Spiegelman saw a pitiless vision of war in what he produced: “The first thing I thought about was Picasso’s Guernica.” Others saw Goya, or the Mexican newspaper cartoonist Jose Guadalupe Posada (for his gruesome subjects and comic readability), Käthe Kollwitz (community), and Wifredo Lam’s mute angular figures on the borders of abstraction. Not to mention the clenched human forms of Francis Bacon.

At the opening of the exhibition at James Cohan Gallery, Spiegelman said for years he has been interested in finding artists who told stories in pictures, who make narratives without words. He was searching for those who bridged the gap between the Belgian artist Franz Masereel (1889-1972), a maker of “wordless” woodcut novels (now seen as precursors of graphic novels) and makers of comics like himself. Learning in the course of his research that Lewen was still alive, Spiegelman met the older man in 2014 and they became friends. At the time, Lewen’s favorite painter was Hieronymus Bosch; he was struggling to make up his mind about Auguste Rodin.

Saying that Lewen was beset by a restless imagination is like saying that Ingres could draw. Modest, but puckish, the prolific Lewen used to warn those impressed by his vast output that he suffered from “diarrhea of the brain.” At the current show, Spiegelman was asked about that self-characterization: “I can say this and still champion him, I love him and I love his work, but a lot of it was diuretic shit. It was just part of moving his hand and waiting for the next inspiration to strike, and it kept striking, which was one of the most amazing things about him.”

The latest works on view in New York, covering one wall in the gallery, are of figures that Lewen called “Ghosts.” He made about 200 of them. Hanging without frames, as Lewen instructed, the standing or vertical portraits (some of them self-portraits) that I saw were indeed spectral, some surfaces were finished with paint or other materials: there was a surprising range of textures. Those surface improvisations came as no surprise, given that this was a man who, in his nineties, said he was kept alive each day by curiosity about what he might paint once he got out of bed.

A scene from Parade, 1950. Photo: courtesy of James Cohan Gallery

What struck me was their transparency, an illusion of near-infinite pictorial depth. You can see into them, as you can with Giacometti’s dense drawings, but here the feeling is hauntingly spatial. They compel you to keep looking inside.

Yet another reason to visit a show filled with discoveries.

Below is an interview with Art Spiegelman and the director of the Menil Collection in Houston, where Parade was exhibited last year.

David D’Arcy lives in New York. For years, he was a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

Tagged: Art Spiegelman, Si Lewen, anti-war art, graphic novel, parade