Book Review: “The Boy From Kyiv” — The Next Big Deal

By Debra Cash

As the first draft of documenting choreographer Alexei Ratmansky’s career, this book will be invaluable, but by the end of it, the story may look somewhat different.

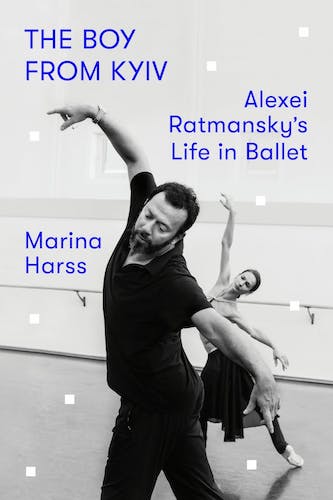

The Boy From Kyiv: Alexei Ratmansky’s Life in Ballet by Marina Harss. Farrar Straus Giroux, 496 pages, $35.

When Shakespeare died, did London theatre lovers go around confiding to each other in doleful or thrilled voices that theatre, as an art, was pretty much over? That while they had been alive to experience its last flowering, nothing would ever be worth enjoying again?

That’s what happened to New Yorkers after the death, in 1983, of George Balanchine, a prolific colossus who unquestionably shepherded the Russian classical tradition into a new world of modern geometries and jazz accents that was dubbed “neoclassical.” And, with his patrons and friends (Lincoln Kirstein, Robert Gottlieb, some deep-pocketed donors), he built not one but two great American institutions, the New York City Ballet (NYCB) and its feeder school, the School of American Ballet (SAB). It was always clear that his death would end an era.

Many New York dance lovers — especially those with deep Balanchinian connections, such as Jennifer Homans — are sure that there is no future for classical ballet, while others have spent the last 40 years testing whether a choreographer might emerge to be the “next” Balanchine, the replacement that would make the persistence of an expensive, Eurocentric, proscenium art worthwhile. There have been a number of candidates in years past, mostly dancers-turned-choreographers from NYCB’s ranks, most visibly Christopher Wheeldon and Justin Peck.

Emerging from the pack is a choreographer who, like Balanchine, drew deep from the Russian academic tradition and then tweaked the classical tradition to suit his own interests: Alexei Ratmansky. In her new biography, The Boy from Kyiv, Marina Harss, a freelancer whose upcoming dance highlights for the New Yorker are penned with a keen appreciation of the local scene, gently heaves a sigh of relief: grand ballet is not over yet.

Harss’s telling of Ratmansky’s life to date traces a peripatetic if not restless life: the studios and languages may change, but the work in the studio stays on the same trajectory. Born to an art-appreciating, free-thinking family in St. Petersburg in 1968, Ratmansky had ballet in his bones: his Ukrainian father, who was Jewish, had been a gymnast and, in an aside that Harss does not explore, his great-aunt was the granddaughter of Lev Ivanov, famous as the choreographer of the second and fourth acts of the original Swan Lake. When he was 10 and growing up in Kyiv, Alexei auditioned for the Bolshoi school in Moscow. He got in. On the bell curve, his natural physical gifts were average, his teachers would remember, but he made up for that with unusual musicality and an analytical intelligence.

One of the strengths of Harss’s writing is her precise descriptions of how certain training techniques actually transform the capacity of a dancer’s body. Landing a jump in four beats, from toe to heel, a technique he learned in Moscow, would create a “feline quality” and was also apt to develop bulk in a dancer’s thigh muscles. Balanchine ballerina Merrill Ashley taught him to cross his legs more in tendu “as if moving between two panes of glass.” For some readers this will be so much inside baseball, but at a time when American dance is all about cross-training, the idea that certain studio techniques — not just natural gifts — build certain types of physical instruments is worth heeding.

Ratmansky performed in the Ukraine, in Winnipeg, and Copenhagen. He was an accomplished dancer, but not a showstopping one: choreography called. Even as a student, he told Harss, “I would wait for the teacher to stop talking and switch on the music so I could picture ballets. It was like having a little TV in my head.” As an adult, he would add, “when I imagine the choreography, it is as if it existed already.… I have to try to learn about it by walking around it and looking at it, asking questions, waiting for answers.” He honed his craft creating short pieces for ballet competitions, pieces that often included injections of refreshing humor. That work was noticed by ballet star Nina Ananiashvili, who was organizing tours for freelancing Russian and American dancers to tour between seasons. He continued freelancing as a choreographer, danced with the Royal Danish Ballet, and became a father.

At 35, Ratmansky caught the brass ring. Astonishingly, he was tapped to lead Moscow’s Bolshoi Ballet on the basis of freelance work abroad and works that had been presented in Russia. A 2003 effort that particularly delighted his high-profile admirers was his ballet The Bright Stream, a comic reworking of a 1935 ballet set to music by Shostakovich, complete with disguised identities, classical ballet larks, and jokes at Stalin’s expense.

Ratmansky would last at the Bolshoi four years, revising classics and creating new works. Ultimately, his tenure was done in by the company’s sclerotic bureaucracy, although by all reports he had done a good job of sweeping away many of the Bolshoi’s cobwebs. Harss has a taste for taking the temperature of institutions as well as individual artists, and that serves her well as the narrative moves across countries where ballet remains valuable.

Ratmansky was lured to New York. Harss spills the beans on the mystery of the bidding war between New York City Ballet and American Ballet Theater, describing American Ballet Theater’s winning offer of a long leash: he would work for ABT for 20 weeks a year, and then could spend the rest of his time doing as he liked. There was no noncompete clause. He spent 13 years there. Last summer he moved across the Lincoln Center Plaza to take a similar, independent role in the house that Balanchine built.

Harss’s biography comes as close to being authorized as could be imagined. While it’s clear that she spoke to many family members and dancers in his orbit, all of them seem to agree he’s an amiable, hardworking fellow whose only vice seems to be his single-mindedness. If there were ballets that were failures, they were failures because the dancers resisted his style, the audience didn’t get it, or he himself deemed them so. There are elisions, especially about his family life: the dancer wife, Tatiana, whose own career was left to chill, has become a kind helpmate-cum-choreographic-assistant; son Vasily gets to take vacations with his dad, but supporting the relentless pace of his career as a “creation junkie” seems to be part of the demanded sacrifice. As the first draft of documenting his career, The Boy From Kyiv will be invaluable, but by the end of it, the story may look somewhat different.

Harss’s biography comes as close to being authorized as could be imagined. While it’s clear that she spoke to many family members and dancers in his orbit, all of them seem to agree he’s an amiable, hardworking fellow whose only vice seems to be his single-mindedness. If there were ballets that were failures, they were failures because the dancers resisted his style, the audience didn’t get it, or he himself deemed them so. There are elisions, especially about his family life: the dancer wife, Tatiana, whose own career was left to chill, has become a kind helpmate-cum-choreographic-assistant; son Vasily gets to take vacations with his dad, but supporting the relentless pace of his career as a “creation junkie” seems to be part of the demanded sacrifice. As the first draft of documenting his career, The Boy From Kyiv will be invaluable, but by the end of it, the story may look somewhat different.

Harss has clearly watched all the videos she can of Ratmansky’s works, but her descriptions tend to rely on scenarios rather than descriptions, giving those of us without access to the performances or films little impression of what the ballets looked like and why they got the reactions that they did. Interpolated references to the war in Ukraine — Ratmansky has been quoted as saying he will never return to Russia as long as Putin is in power — will, one hopes, seem dated by the time this book has cooled on library shelves. The publisher seems to have demanded a topical tie-in, even though the entire volume speaks of the ways individual national identity is reshaped in the crucible of ballet’s internationalism. His classmates may have called him “the boy from Kyiv” and he muses on his identity raised as a “Soviet man,” but Ratmansky is a cosmopolitan who lives in New York — and out of a suitcase.

Balletomanes can see Ratmansky’s newest work in person this coming winter season, his first since joining New York City Ballet as artist in residence. On the website, it’s just called New Ratmansky. His name is enough to sell the tickets.

Debra Cash is a Founding Contributor to the Arts Fuse and a member of its Board.

A very personal review, not generic. I like it a lot.

Perceptive analysis of both the artist and the biographer. A wonderful review!

An excellent review by a perceptive, erudite critic, so well versed in the greater dance world. Her comment, “the entire volume speaks of the ways individual national identity is reshaped in the crucible of ballet’s internationalism,” makes me want to read this book. The way a specific international art form with its own rules reshapes national identities could be applied to other artists and attests to the power of artistic disciplines.