Jazz Album Review: Eddie Henderson’s “Witness to History” — Veteran Talents

By Michael Ullman

These witnesses to history are no longer playing with the fire of their youth, but they exude the confidence, warmth, and sure instincts of veterans.

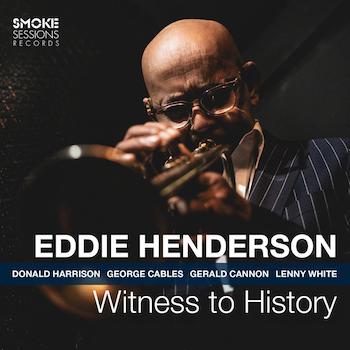

Eddie Henderson, Witness to History (Smoke Sessions)

I first heard Eddie Henderson in Ann Arbor around 1970 when he was with the spacy Herbie Hancock band that came to be called Mwandishi. Hancock introduced Henderson as Doctor Eddie Henderson, which sounded a bit like a joke. But Hancock wasn’t teasing the trumpeter: Henderson was not only the trumpet player with one of the hottest bands in jazz: he was a practicing medical doctor. Now, as I learned in the notes to Witness in History, when Henderson was in high school he was a competitive figure skater: the first Black man to compete nationally in that unlikely sport. We’re lucky he stuck with music.

Inevitably, when he joined Herbie Hancock’s band soon after Hancock left Miles Davis, Henderson would be compared to the Prince of Darkness, as Miles was then frequently called.

Henderson wasn’t afraid of the comparison. (Could Miles even begin to figure skate?) In 2002, for instance, he bearded the dragon with his recording of nine tunes associated with Miles Davis: So What (on Columbia), which included Henderson’s take on “All Blues” and “Someday My Prince Will Come.” It is now a half century after Doctor Henderson recorded his first LP as a leader, his Inside Out with Davis veterans Hancock and Bennie Maupin. On Witness to History, Henderson returns confidently, soberly, to two tunes associated with Miles: the ballad “It Never Entered My Mind,” which Davis recorded on Workin’, and “Freedom Jazz Dance,” the Eddie Harris classic Davis recorded in 1966 and which was issued on Miles Smiles. Henderson retains the Miles Davis arrangement of “Freedom Jazz Dance,”respecting its pauses between phrases of the catchy melody. (Davis said he couldn’t play the piece as Eddie Harris wrote and recorded it.) The new Henderson recording also exposes his fine rhythm section: pianist George Cables (born in 1944!), bassist Gerald Cannon, and drummer Lenny White, another guy in his 70s. Alto saxophonist Donald Harrison also solos on what is an easy-going rendition of “Freedom Jazz Dance.” Cables is given the task of rendering the introduction to “It Never Entered My Mind,” thereby inviting comparison with Red Garland’s perfect work on Workin’. Cables’s gentle solo later in the piece serves as a sweetly meditative chorus. Henderson performs the piece in a whisper, with occasional smeared notes and plenty of space. It’s not Miles, but it’s lovely.

Elsewhere, Henderson notes that he “chose songs for this album that stood out in my mind for shaping my musical destiny.” The tunes are “building blocks of my musical character.” The building blocks include Lee Morgan’s delightful swinger “Totem Pole” from The Sidewinder. Henderson learned “Born to Be Blue” from Freddie Hubbard, perhaps from the latter’s 1981 Pablo album with the same name. (I am guessing he heard Hubbard play “Born to Be Blue” earlier, in a live performance.) Henderson bounces the melody, emphasizing the tune’s skips, before he solos in his relaxed manner with his fetching tone. There’s one remarkable original. Netsuke Henderson, Eddie’s wife, wrote “I Am Going to Miss You, My Darling” as a tender tribute to her husband, who is often out on the road. It’s one of those melodies that seem inevitable, and Henderson plays it with authority and what sounds to me like deep feeling. These witnesses to history are no longer playing with the fire of their youth, but they exude the confidence, warmth, and sure instincts of veterans. I wish I’d seen Doctor Henderson skate.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.