Film Reviews: The Criterion Collection’s “The Ranown Westerns” — Absolutely Swell

By Betsy Sherman

Cinephiles revere a group of movies, known as the Ranown cycle, that starred Randolph Scott and were cannily directed by Budd Boetticher.

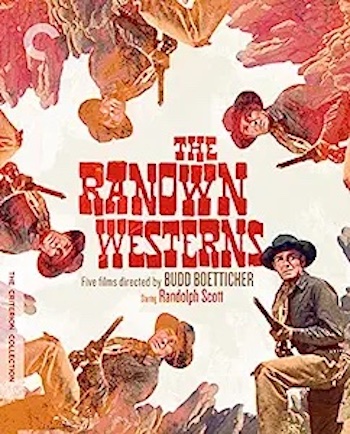

The Ranown Westerns: Five Films Directed by Budd Boetticher – A six-disc Blu-ray + 4K Ultra HD combo boxed set from The Criterion Collection.

All hail Randolph Scott! Cue the heavenly choir!

Fans of Blazing Saddles will remember when the townspeople bow their heads as voices intone: “Raaan-dolfff Scott.” This Western hero of the silver screen is little remembered today (though if you google his and Cary Grant’s names together, you’ll encounter a slice of Hollywood gossip). Starting with his first picture in 1928, Scott’s career touched a variety of genres, but by the 1950s he was best known for his cowboy roles. At an age when many performers can’t find work, he made the list of Top Ten Money Making Stars four times.

Cinephiles revere a group of movies starring Scott that were cannily directed by Budd Boetticher. Since they came out of the production company formed by Randy and executive producer Harry Joe Brown, they’ve become known as the Ranown cycle (said like “renown”). These five films dating from 1957-1960 are collected in a new Bluray + 4K Ultra HD combo set (the same content in each format) released by The Criterion Collection. It’s titled The Ranown Westerns, and it’s absolutely swell. Within a genre that is often formulaic — and sometimes problematic — these works can be embraced for their economic, powerful storytelling and their aesthetically pleasing placement of humans and horses in the landscape.

Boetticher (1916-2001), pronounced Bet-i-ker, had two claims to fame, Westerns and bullfighting movies — even though, out of 51 films, he directed only 10 Westerns and three bullfighting pics (his years as a “gringo” bullfighter in Mexico solidified a passion he held dear his whole life). He was underappreciated in Hollywood, but acclaimed in Europe. Happily, he was able to spend his last few decades being fêted at film festivals and retrospectives. I saw him on two Boston-area visits: at the Museum of Fine Arts in February 1986 as part of a Director’s Guild tour, and at the Harvard Film Archive in April 1993 for the French-American Film Festival.

The titles in the Criterion set are The Tall T (1957), Decision at Sundown (1957), Buchanan Rides Alone (1958), Ride Lonesome (1959), and Comanche Station (1960). Released by Columbia Pictures, they were made on tight budgets and 18-day shooting schedules (they each run 70-something minutes). For B-movies, their cast lists hold some impressive names. Many of these actors got their big breaks after appearing in these Boetticher movies; their performances for Budd launched them. (Boetticher and Scott also made two other pictures: the non-Ranown Seven Men from Now (1956) and Westbound (1958).) The set also includes a fine slate of documentary supplements.

There are a few divisions one can make to separate the titles. Ride Lonesome, Comanche Station, and The Tall T take place among small groups of people, in outdoor locations, and except for a short section of The Tall T, away from towns. Decision at Sundown and Buchanan Rides Alone take place in communities, one of which the Scott character enters deliberately, the other by chance. Another distinction involves the screenwriters. Burt Kennedy was an invaluable partner to Boetticher and Scott. His witty, thoughtful scripts set the template for these westerns. Charles Lang scripted the movies set in communities. However, Budd ended up chucking Lang’s script for Buchanan Rides Alone, bringing Kennedy on set to brainstorm improvisations.

As Monument Valley was to John Ford, California’s Lone Pine rock formation was to Boetticher, making his movies instantly identifiable (in the distance are the Sierra Nevada). The bulbous volcanic rocks contrasted with the straight lines and angles of the 60-ish Scott’s toned body and leathery face. But it isn’t only the landscape that threads the outdoor films together. Viewers get to know and judge the characters through a series of conversations between twosomes. Part of what is probed is whether words can be taken at face value, but personalities bump up against each other and are slowly revealed.

Scott’s capable Westerners are seldom caught off guard. The men he plays (some of them former sheriffs) have a wealth of experience, well-honed reflexes, and can think several steps ahead. His moral compass guides him, but he can be pushed off balance when bent on revenge. He doesn’t always say the true thing out loud, but that is in order to protect his privacy. Director Paul Schrader had these thoughts: “In Scott, [Boetticher] found that exemplar of that kind of Puritan, sexually repressed moralist, who was also a man of action, all those sort of contradictions. Scott wore them very well and he wore them very effortlessly.”

A fun aspect of the Ranowns, and a source of their intriguing ambiguity, is the “sympathetic villain” who tries to convince Scott they have much in common. It’s the subject of Glenn Kenny’s essay in the accompanying booklet, The Outlaw Variations: The Ranown Westerns’ Finely Drawn Antagonists. He writes, “On the moral ladder, [the Boetticher/Scott protagonist] sometimes stands only one or two rungs above the men he opposes. And the men he opposes, venal though they may be, almost always have their reasons.” What’s more, the baddies’ sidekicks can be hilarious scene-stealers, akin to Shakespearean clowns.

Randolph Scott as Pat Brennan with Richard Boone as Frank Usher in The Tall T.

Martin Scorsese introduces The Tall T and Ride Lonesome. He recalls seeing the former when it came out, when he was 11. He says, “We knew there was something different [from other Westerns] going on … we were made to pay attention by the nature of the tension in the frame.” He compares the flat, austere spaces in the film to a bullfight arena, “so every movement means something.”

Note on the reviews: I was able to watch the Blu-ray discs, which were excellent quality, but not the 4K Ultra HDs (for lack of equipment).

The Tall T [Technicolor 1.85:1 aspect ratio]. Adapted by Burt Kennedy from the story The Captives by Elmore Leonard. The first Ranown establishes an opening shot that will recur, as Randolph Scott, here playing Pat Brennan, rides alone through the rocks of Lone Pine. His destination is the town of Contention. The man of few words amiably exchanges some with a stationmaster. Brennan accepts a coin from the man’s young son Jeff, gladly agreeing to buy him cherry-striped candy in town and deliver it on the way back. In Contention, Brennan chats with his grizzled stagecoach-driver friend Rintoon (Arthur Hunnicut) and meets middle-aged newlyweds Doretta Gateway and Willard Mims (Maureen O’Sullivan and John Hubbard). To the townspeople, the weaselly Willard has saved Doretta from old maidhood by marrying her for her money. These four characters meet with tragedy at the hands of three bad men, experienced outlaw Frank Usher (Richard Boone, later to star in TV’s Have Gun, Will Travel) and lackeys played by Skip Hormeier and Henry Silva (the former basically a big kid, the latter a stone-cold killer). The way station is revisited and that candy comes to symbolize innocence violated, as it ends up enjoyed not by Jeff but by his murderer.

Usher and his boys hold them hostage. Their cruelty is matched by Willard’s; he hopes to save himself by setting up a ransom payment from Doretta’s father, a copper mine owner, and abandoning his bride. Brennan plays it cool, trying to devise an escape for Doretta and himself. Part of that involves encouraging the traumatized woman to have faith in her own strength. O’Sullivan, who famously played Jane in the Johnny Weismuller Tarzan series, is the only actress from Scott’s generation in the series (younger actresses look to his characters as alternately potential lover and father figure). The gregarious Frank can almost pass for a redeemable fellow, as he tells Brennan about wanting to go straight. But he has no qualms about using Silva’s character to do his dirty work. The film’s brisk pacing doesn’t preclude some genuine tension, and it’s beautifully shot by Charles Lawton, Jr. The audio commentary by film scholar Jeanine Basinger is as crystal clear, concise, and on point as Boetticher’s movies are.

Decision at Sundown [Technicolor 1.85:1 aspect ratio]. Adapted by Charles Lang from the novel of that name by Vernon L. Fluharty. For a film that seems like it should draw a lot of interest because of its differences from the others — it’s the only one in which Scott’s character has a sidekick, and the one in which his emotions cause his judgment to be faulty — it’s the least interesting (an opinion shared by Boetticher). It starts not with a lone rider in the distance, but with a stagecoach on the horizon. The buddy, Sam (Noah Beery), is a sounding board for Bart Allison (Scott), who is on a mission of revenge against Tate Kimbrough (John Carroll), the man who seduced his late wife while he was fighting in the Civil War. Unbeknownst to the twosome, they arrive in the town of Sundown on Kimbrough’s wedding day. The groom is a shady big shot who holds the real power in Sundown — politicians, business people, and the sheriff are in his pocket. This is jus’ fine with the amoral citizenry; they crowd the bar, since Kimbrough is paying for drinks that day. After Bart causes a dust-up at the church, the sheriff and his men work to keep him away from Kimbrough, but all signs point to a showdown on main street. The upstanding doctor tries to make peace. Sam gives him the lowdown on Bart and Bart’s wife; the backstory demonstrates how the past can be murky terrain. To sum it up, Decision at Sundown is colorless (no fault of Beery’s), especially compared with the other Ranowns. It doesn’t help that Carroll is a villain, and actor, with little charisma.

Randolph Scott as Buchanan and Craig Stevens as Abe Carbo in Buchanan Rides Alone.

[]Buchanan Rides Alone [Columbia Color 1.85:1 aspect ratio]. Adapted by Charles Lang (and Burt Kennedy, uncredited) from the novel The Name’s Buchanan by Jonas Ward. Buchanan isn’t as good as Lonesome, Tall or Comanche, but it’s more enjoyable than Sundown. Its look at a corrupt town is sharper and funnier than its predecessor, and Scott’s craggy protagonist is looser than his other Ranown characters. On his way home to West Texas, Buchanan lopes into the Southwest border burg of Agry Town, where the Agry brothers hold the power. Top dog is Judge Simon Agry (Tol Avery). Brother Lew Agry (Barry Kelly), the sheriff, is palpably jealous of his elder’s position. Slow-witted, corpulent hotel proprietor Amos (Peter Whitney is a hoot) tries to take advantage of the ill-gotten perks without ruffling feathers. The plot gets going when Simon’s carouser son Roy is killed by a young Mexican man for assaulting a woman. Buchanan gets mixed up in the action after the sham trial of the Mexican, Juan de la Vega (the flashy Manuel Rojas). Having seen and experienced the injustice and sadism endemic in Agry Town, Buchanan pitches in to help (though the boy is no slouch at helping himself), which leads to lively chases and shootouts. Actor Craig Stevens, later to become TV private eye Peter Gunn, plays Simon’s fixer Abe Carbo. Too vague to rate the “sympathetic villain” moniker, Carbo is most valuable in his parting exchange with Buchanan.

Ride Lonesome [Eastman Color, CinemaScope 2.35:1 aspect ratio]. It’s back to Burt Kennedy’s Tall T template with the pinnacle of the cycle, and its first shot in CinemaScope, the taut nailbiter Ride Lonesome. As if to honor the wider screen, there are more factions of characters. There’s Scott as Ben Brigade, a man with a mission; the trademark sympathetic villains Sam Boone (a pre-Bonanza Pernell Roberts) and Whit (pre-movie-stardom James Coburn); vicious villains Billy John (James Best, who became a busy character actor) and his brother Frank (pre-Sergio Leone Lee Van Cleef); Indian warriors on the horizon; and a just-widowed woman swept up in the drama (Carrie Lane, played by the wonderful Karen Steele). The performances are terrific.

Both Brigade and contingent two are hunting for whining killer Billy. Brigade gets Billy first, but he has more on his mind than the reward. Boone and Whit want the reward, but not only for its dollars and cents value. They’ve learned a new word — amnesty –which is what will be given to whoever turns Billy in. Boone, who has a checkered past, says with conviction, there’s “one man between me and startin’ life clean.” Well, there’s Billy, and now there’s Brigade. But they’ll all have to stick together, since Billy’s ruthless brother Frank is coming to his rescue, and the Mescalero tribe is bound to attack (Native Americans aren’t much more than a device to briefly cohere the good white guys and the bad white guys).

The male gaze, trained on Carrie, is practically a character itself. But it’s more amusing than icky, with Kennedy’s snappy dialogue delivered by the very watchable Roberts, either passing on his questionable philosophy about women to dim Whit or pitching woo to Carrie in the moonlight. Steele, a tall blonde wearing a non-period-accurate ‘50s fitted blouse, brings realism to Carrie’s reactions. Ride Lonesome also boasts a cool musical theme and a haunting final shot. The commentary by film historian Jeremy Arnold is peppered with stories shared with him by his late friend Budd.

Nancy Gates as Nancy Lowe and Randolph Scott as Jefferson Cody in Comanche Station.

Comanche Station [Eastman Color, CinemaScope 2.35:1 aspect ratio]. The final collaboration has intriguing story elements that were clearly a challenge to flesh out in a mere 73 minutes, but it’s still an engrossing, well played entry. The enigmatic first nine minutes have no English dialogue, as Jefferson Cody (Scott) attempts a trade with Comanche Indians. His objective? Free a captive white woman. As he rides across the rocky terrain with the woman, Mrs. Nancy Lowe (Nancy Gates), and crosses paths with this movie’s passel of outlaws (Claude Akins as the cruel but sometimes charming Ben Lane, leading subordinates Richard Rust as Dobie and Skip Hormeier as Frank), Cody faces numerous hurdles: the gunmen, the Comanches tracking them, and the demons of his past. The outlaws too were looking for Mrs. Lowe, for the fat reward (which Cody didn’t know about).

Here are three standout moments in the drama: First, the newly freed Nancy, in tattered clothing, sitting on a rock with a blanket covering her lower body, verbalizes her trepidation about going home. The supposition, not explicitly stated, is that she was raped by non-whites — or, as it probably would be put, “defiled by savages” — which would leave her ostracized by white society. She asks Cody, “If you had a woman taken by Comanches, how would you feel?” He answers with conviction, “If I loved her, it wouldn’t matter at all.” Second, we find out that Cody had been Lane’s commanding officer in the Army, and had “busted him out” of the service for raiding a village of peaceful Indians, murdering and taking scalps. Cody is still angry and Lane is unrepentant. Third, rather than just comedy, there’s substance in the banter between the two sidekicks. Rust is affecting as Dobie, a lost boy of the sagebrush who talks about his hope that he’ll someday “amount to somethin’.”

In the commentary, director Taylor Hackford (An Officer and a Gentleman) speaks as a fan, colleague, and friend of Boetticher. He lends behind-the-camera knowledge of how scenes were shot, reminds us of Budd’s love for and knowledge about horses, and gets a kick out of Kennedy’s great dialogue.

And that was the end of the Ranown cycle. Westerns were thriving on television, but not so much at theaters anymore. The psychological Western, which Boetticher thought was ludicrous, had taken hold (he maintained that cowboys were uncomplicated people, without impressive vocabularies). Scott went on to team with fellow old-timer Joel McCrea in Sam Peckinpah’s elegiac Ride the High Country.

It’s great getting to know Boetticher from the boxed set’s hours of extras. Here are the bare bones of his colorful bio:

As a baby, he was adopted by an affluent family in Evansville, Indiana, and named Oscar Boetticher, Jr. Bullied as a child (“I was a sissy,” he says “… spoiled rotten”), he built himself up into an athlete, running track, boxing, and playing football for Ohio State. While on a break because of a football injury, he tooled around Mexico, and, on a whim, asked to learn bullfighting. It was by no means easy, but he succeeded. Through producer Hal Roach, a family friend, he got an interview for the job of technical advisor to director Rouben Mamoulian on the bullfighting picture Blood and Sand starring Tyrone Power. He then did minor behind-the-camera work at Roach’s studio, worked as an assistant director, and directed some B-pictures for Columbia and a few “Poverty Row” studios. His first personal movie as a director was The Bullfighter and the Lady (1951). He made many action movies before his collaborations with Scott. In between each Ranown picture, he’d head to Mexico to film his friend Carlos Arruza’s bullfights, for a picture that was at first going to be fictionalized, but eventually became a documentary 12 years in the making (the director underwent a dangerous ordeal getting it shot, including being thrown into a Mexican jail). He wrote about making Arruza (1959-1968) in his 1989 book When in Disgrace.

Randolph Scott and Budd Boetticher. Photo: Wiki Common

Budd Boetticher: A Man Can Do That (2005) is your standard biographical film with clips, about an anything but standard life. Produced by Clint Eastwood’s company for Turner Classic Movies, it’s a good place to start in getting to know this masterful director. Clint and Quentin Tarantino share the screen to extol Budd and his work. There are also interviews with Boetticher (some archival), as well as admirers including Robert Towne, Peter Bogdanovich, Paul Schrader and Taylor Hackford.

Boetticher Rides Again (1995) is a meta psychodrama-doc in which the subject and the French filmmakers are at loggerheads much of the time. It’s an entry in the esteemed, long-running TV series Cinéma de notre temps (Cinema of Our Time). In its opening, the interviewer kicks up dust driving a car through the Lone Pine rock formations, amusingly mimicking Randolph Scott’s characters. At his place near San Diego, Boetticher shows the crew his Portuguese Lusitanian horses, on which he and his wife Mary led equestrian exhibitions. The horses are noted for their use in horseback bullfighting. The French people want to do their show in Lone Pine because the Ranown cycle is widely known and loved in France. Budd is miffed they haven’t asked to shoot inside his house; he’s eager to show off his French and Spanish painting collection. He wants to talk about how happy his life is, and his efforts to raise money to shoot a film in Spain. They want to plumb the philosophical depths of the Ranowns. Not Budd’s style. By the time the car retraces its tracks on the dusty road, it’s been an interesting and backhandedly informative hour.

Visiting Budd Boetticher (shot 1999, edited 2018) is a 37-minute German production that contains some anecdotes that are in the other documentaries, and some fresh ones (like how he was a “herder” of Laurel and Hardy when he worked at Hal Roach Studio, and what he thought of the first burlesque show he saw at age 14). Maybe director Eckhart Schmidt saw the French documentary; he’s completely obedient, and we don’t even hear the questions asked. Budd is in a comfy chair in his home, with a cat stretching and sleeping on the next chair over.

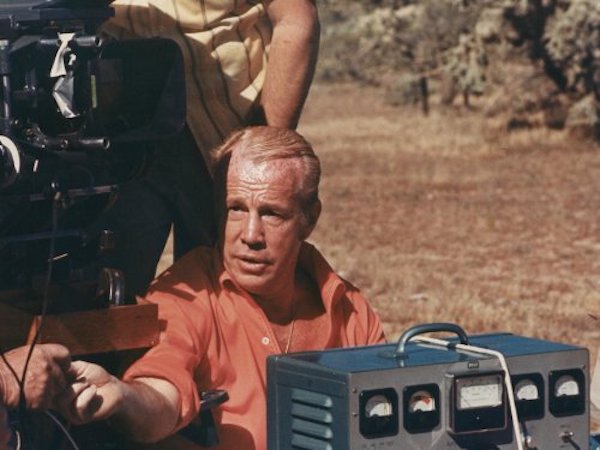

Budd Boetticher on location. Photo: Wiki Common

Budd Boetticher and Jim Kitses – Film historian and professor Jim Kitses’ book on Westerns, Horizons West, was named after a Boetticher movie. This hour-long audio recording captures a Q&A between Budd and Kitses at a 1969 retrospective. It’s very informative, even though, as usual, the director tries to evade matters of philosophy in favor of making the audience laugh. When asked about the similarity of his scripts, he says, “I would rather do something over and over again, and do it well, than to get all of the junk which is submitted to us to direct, which I just refuse to do.” He also says, “I am a showboat in my personal life … I try to keep it out of the pictures.”

Farran Smith Nehme on actor Randolph Scott – Film scholar Nehme fills us in on the North Carolina-born actor in this 25-minute featurette. It’s true, the main man in the saddle co-starred in two Fred Astaire-Ginger Rogers movies, Roberta and Follow the Fleet.

Super 8mm home-movie version of Comanche Station – Ever wonder what people did before VCRs? Well, if you wanted something more mobile than View-Master, you could get an 8mm film projector and order abbreviated versions of theatrical movies. This is heinous, right? Who makes these editing decisions? This Comanche is boiled down to 20 minutes. All the bang-bang-bang without the nuance. It’s a nice historical curiosity.

Budd Boetticher : A Study in Self-Determination This hour-long 1971 gem was directed by Alan L. Muir and produced by Taylor Hackford for Los Angeles station KCET. At an outdoor riding arena, Hackford hosts an interview and bullfighting (sans bull) demonstration, and a trim and energetic Boetticher shines. Budd talks about his bullfighting and Hollywood careers and his documentary Arruza, just being released in ’71. On the ground, he demonstrates different passes with a hot pink cape, although his practice had changed to the Portuguese style of bullfighting on horseback, called rejoneo. He thrillingly demonstrates the technique, plunging banderillas into a wheeled apparatus with bull’s horns on it from astride a white Andalusian horse.

His grin affirms one of his quips: “After bulls, you’re not afraid of studios or producers.”

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for the Boston Globe, Boston Phoenix, and Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.

Great article! I read it through with tremendous pleasure. Why was Seven Men From Now, my favorite Boetticher, not part of this series? I also recommend his final film, A Time for Dying, which probably has the most grim, pessimistic conclusion of any western ever.

Hi Gerry,

Seven Men From Now wasn’t produced by Scott and Harry Joe Brown, but by John Wayne and his production company Batjac, and distributed by Warner Bros. rather than Columbia. Luckily, Wayne declined to act in it after John Ford offered him The Searchers, and asked Scott to take over the role. Otherwise, the Ranown cycle may not have happened.

Hi there

Interesting review.

Keep up the good work.

Geoff