Book Review: “We Carry Their Bones” — Life and Death at a Reform School During Jim Crow

By Jeremy Ray Jewell

We Carry Their Bones arrives at a time of increased interest in the history of racism and reform schools, particularly in Florida.

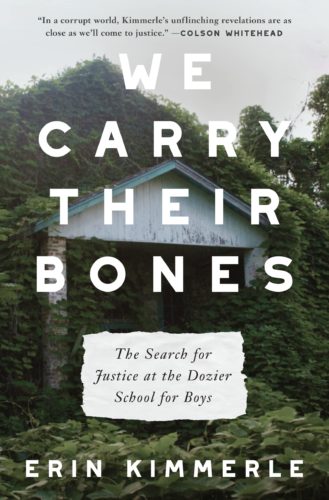

We Carry Their Bones: The Search for Justice at the Dozier School for Boys by Erin Kimmerle. William Morrow, 256 pages, $22.39.

In We Carry Their Bones, University of South Florida forensic anthropologist Dr. Erin Kimmerle details her investigation into the graveyard at the notorious Dozier School for Boys in Marianna, Florida. From 1900 to 2011 the institution became the stuff of local legend throughout the state. At one time, it was the largest juvenile reform school in the country. Throughout Dozier’s existence, stories about the mistreatment of its juvenile detainees were rife: rape, torture, cruelty, and possible murder. Multiple investigations by state and federal authorities were undertaken. Most of the alleged victims had been incarcerated for what amounted to nothing more than being penniless: the majority were Black children placed in the segregated school’s custody. Survivors of Dozier formed a group known as “The White House Boys,” named for the concrete block detention building where most of the worst abuse is said to have taken place.

In We Carry Their Bones, University of South Florida forensic anthropologist Dr. Erin Kimmerle details her investigation into the graveyard at the notorious Dozier School for Boys in Marianna, Florida. From 1900 to 2011 the institution became the stuff of local legend throughout the state. At one time, it was the largest juvenile reform school in the country. Throughout Dozier’s existence, stories about the mistreatment of its juvenile detainees were rife: rape, torture, cruelty, and possible murder. Multiple investigations by state and federal authorities were undertaken. Most of the alleged victims had been incarcerated for what amounted to nothing more than being penniless: the majority were Black children placed in the segregated school’s custody. Survivors of Dozier formed a group known as “The White House Boys,” named for the concrete block detention building where most of the worst abuse is said to have taken place.

Kimmerle’s book is billed as “a detailed account of Jim Crow America and an indictment of the reform school system as we know it,” “a fascinating dive into the science of forensic anthropology,” and a retelling of “an endeavor that created a political firestorm and a dramatic reckoning with racism and shame in the legacy of America.” As a young Floridian, I spent time in that state’s juvenile system at the turn of this century and its excessively punitive nature and racial and economic disparities were evident. And I have witnessed, growing up in the “New South,” repeated attempts to erase its uncomfortable history. We Carry Their Bones‘ flap copy claims that the book is an expose, a deep dive into the discovery of hundreds of unmarked graves at Dozier. I expected to find historical antecedents that validated my own experiences. In the end, anthropologist and I found less than we expected to find.

We Carry Their Bones offers occasional glimpses into the workings of forensic anthropology, but it supplies a surface look at a complex field. As for a detailed account of Jim Crow, Kimmerle acknowledges that she isn’t from the South and depends on others to supply the needed cultural/historical context. Her research coordinates are different, reflecting her experiences as a forensic anthropologist in Peru, Bermuda, Nigeria, and the former Yugoslavia. To her credit, the anthropologist makes her distance from the world of Dozier clear via the inclusion of memoir material, though she sometimes minimizes the professionalism of the historians she depends on.

We Carry Their Bones arrives at a time of increased interest in the history of racism and reform schools, particularly in Florida. Colson Whitehead’s best-selling 2019 novel Nickel Boys was based on the Dozier School for Boys, located in a town in the Florida panhandle just an hour’s drive from the state capital.

Juvenile reform schools such as Dozier resembled Indian schools in notable ways. Often established as “industrial schools,” their claims about “reform” were limited to educating its pupils for menial labor. Dozier also reflected Jim Crow in the Deep South — the criminalization of poverty (via vagrancy laws) licensed the exploitation of convict labor. The latter was legitimized by a loophole in the 13th Amendment that permitted slavery to exist as “punishment for a crime.” Many people in the community benefited from the unpaid labor performed by Dozier’s inmates, which might explain why so many locals resist confronting the school’s horrific history.

To her credit, Kimmerle talks to locals in Marianna who at times cut against caricature: they are not all unreformed bigots, racist apologists, and callous classists, although she does often present them as such. But the book does not live up to its sensational flap copy. The investigation expected to uncover a significantly larger number of dead in the Dozier graveyard than had been previously believed. And that might lead to evidence of murder. But Kimmerle did not uncover these kinds of crimes. What did accomplish was to reunite remains with families, helping them find closure. Kimmerle writes that “I’ve done this type of work for more than twenty years, and never has the family of someone who was missing or murdered told me they didn’t want to know the details.” And that is commendable. Even unearthing what was there (55 dead versus 31 crosses) may have been justified, given what she believed to be there.

Who made the choice to go ahead with Kimmerle’s investigation? Millions of dollars were appropriated by the state to finance her initial investigation, then a second, and then a lidar study of the campus. It is useful to keep in mind that unmarked graves – of the enslaved, in particular – are common in the South. When Kimmerle’s original petition to exhume the remains at Dozier was initially denied, the judge mentioned as much: “There are current Florida laws in place on handling unmarked graves and moving buried human remains.” The judge also referenced that a modern criminal investigation had been performed by the Florida Department of Law Enforcement (FDLE) on the site, which found no need to exhume the graves. The report indicated that the number of crosses in the cemetery did not reflect the number that had been buried there. Still, using school records, sworn testimonies, and archival evidence, the researchers determined that no reasonable evidence for a civil or homicide case had been demonstrated.

Dining hall construction with “White House” in background, 1936. Photo: Wikipedia.

The report’s judgment doesn’t jibe with Kimmerle’s assumption, articulated by a South Florida columnist, that the school’s authorities were part of “the rural, insular enclave that supplied the guards who administered the brutal beatings and surreptitious burials. It is this prejudice, the assumption of guilt, that undercuts the book’s value. Some of those Kimmerle interviewed have pointed this out in their criticism of We Carry Their Bones. Dale Cox, author of 2014’s Death at Dozier School: The Attempted Assassination of an American City, believes that the forensic anthropologist had her mind made up from the beginning. He insisted, via an email, that she suggested that anyone who disagreed with her suspicion of wrong-doing was part of a deep-fried cabal: “She expressed to me a belief that many had been murdered by gun-toting guards and by local residents. I disagreed and time (and science) eventually proved that she was wrong.”

Cox also charges that Kimmerle and her team refused to look at archival documents and rejected meetings with Cox and state archaeologists. Cox also indicates that — because of its single-minded search for evidence of homicide — We Carry Their Bones overlooked other forms of criminality at Dozier: “If we think about it, what could the amount of money spent on the cemetery have done to ease the lives of elderly men who could present verifiable claims of abuse at the school? I say verifiable because in many, many cases, this was possible. The original “punishment logs” of students flogged […] still exist. Dr. Kimmerle does not mention them in her reports or books, but that does not mean that they do not exist. In addition, there are records of sexual abuse allegations against some staff members at the school. I believe it would have been possible to create a compensation fund and a reasonable process for former students to apply. The state, however, balked at the idea after spending millions on Kimmerle’s work. I also believe that the outlying properties of the campus (of which there were hundreds of acres of mostly cultivated farm and forest land) should have been sold and the money used to help with a compensation fund.”

I am not going to pick either camp in this discussion here. There are at least two important sides to the story, and We Carry Their Bones only offers one. I don’t doubt that people who worked at the school — who didn’t know about the abuse — believed that they were doing righteous work. Yet facts are facts: Dozier School for Boys was part of a system designed to extract forced labor from poor children, often for no offense other than their own poverty. Could Cox’s disagreement with Kimmerle suggest that he denies the testimonies of the victims, or worse, that he believes they simply deserved their abuse? Kimmerle assumed so, but Cox assures us that this was never true, and that he fully condemns the reform school and convict labor systems. However, those “delinquents” weren’t the ones lynching folks left and right at that same time in Jackson County, or lynching Claude Neal and cutting up his corpse for souvenirs. The lesson to be drawn is that the assumption that maliciousness lies behind all attempts to discern the truth is an obstacle. Arriving at the facts of the matter will be the fruits of a collective effort. If Kimmerle had wanted to arrive at the truth, she needed to enlist others.

Jeremy Ray Jewell hails from Jacksonville, FL. He has an MA in history of ideas from Birkbeck College, University of London, and a BA in philosophy from the University of Massachusetts Boston. His website is www.jeremyrayjewell.com.

Tagged: Dale Cox, Dozier School for Boys, Erin Kimmerle, Jeremy Ray Jewell, Jim Crow America

Dozier was an abusive and awful place. But it was the mundane abuse one would expect at the hands of the uneducated, unskilled, low-paid rednecks who oversaw us. The only problem we had, in their book, was that we just hadn’t had our butts kicked enough to know to act right.

It wasn’t the sensationalized place of nightly rape and murder and an ever-expanding clandestine graveyard that some people have portrayed for their own reasons and the press has exaggerated to unbelievable horrors.

Were you in Okeechobee? I was – I was in Adams Cottage 66-67 and worked in the Kitchen. I was tortured several times. As for the leadership in Okeechobee for the most part these men were very well educated. Also, the Psyphiartist were professional and they sure knew what was going on. When 5 boys a year are raped and molested and then 3-4 murdered it’s pretty sensational to the uneducated. Also, Okeechobee Florida School For Boys also had girls. They beat – raped and tortured those girls too. Not all of them but then when you have 100 people in a room it only takes one with a gun to change the mood in the room. Every child who came through Okeechobee was tortured mentally and many of them physically. May I ask what year you were there?

There is considerable evidence of abuse, sexual and physical, including at Dozier. There are horror stories from the Florida juvenile system through to today. Also, the other commentor’s classist remarks about “rednecks” are extremely counterproductive. 10× better to be a redneck like many of the victims of these places than some snooty pseudo-plantation aristocracy putting working people into those sausage grinders they called schools. That kind of classism, on the part of an outsider academic, is what made this book a flop as far as I am concerned. I thank you for your testimony, Gary. Let’s make a better Florida.