Jazz Album Review: “Hampton Hawes Four!” — Evidence of a Remarkable Talent

By Michael Ullman

Four! is one of Hampton Hawes’s most satisfying sessions, for the variety of the repertoire and the quality of the performances.

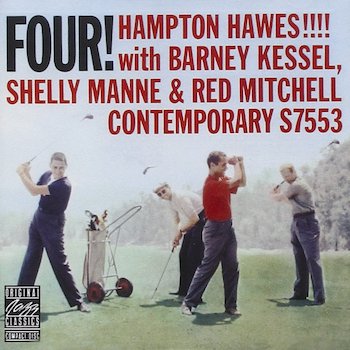

Hampton Hawes Four! (Craft LP in association with Contemporary Records)

Between 1955 and 1958, Contemporary Records, run by the astute Lester Koenig, recorded 10 LPs by the west coast pianist Hampton Hawes. Featuring Barney Kessel on guitar, Red Mitchell on bass, and the nearly ubiquitous Shelly Manne on drums, Four! was the eighth of that series. As he tells it in his autobiography, the stunningly frank Raise Up Off Me, Hawes met Koenig thanks to the intervention of a friend, and the signing was casual: he was introduced and thought, why not? The recording sessions, the most fruitful of Hawes’s career, took place in the breathing space between his stints in the army and in prison. Though he liked the uniforms, he seems to have spent much of his time in the army deftly evading the military police, or suffering from dealing with their disciplining. He was already involved with drugs. His 1958 conviction for narcotics offenses netted him what he called “a dime,” a decade in prison. Miraculously, after five years he was granted a pardon by President John F. Kennedy.

Between 1955 and 1958, Contemporary Records, run by the astute Lester Koenig, recorded 10 LPs by the west coast pianist Hampton Hawes. Featuring Barney Kessel on guitar, Red Mitchell on bass, and the nearly ubiquitous Shelly Manne on drums, Four! was the eighth of that series. As he tells it in his autobiography, the stunningly frank Raise Up Off Me, Hawes met Koenig thanks to the intervention of a friend, and the signing was casual: he was introduced and thought, why not? The recording sessions, the most fruitful of Hawes’s career, took place in the breathing space between his stints in the army and in prison. Though he liked the uniforms, he seems to have spent much of his time in the army deftly evading the military police, or suffering from dealing with their disciplining. He was already involved with drugs. His 1958 conviction for narcotics offenses netted him what he called “a dime,” a decade in prison. Miraculously, after five years he was granted a pardon by President John F. Kennedy.

Hawes was known, perhaps even typecast, as a blues player. He also showed the influence of the gospel music he had heard around his childhood home. (His father was a preacher.) In 1947, while still a teenager, Hawes was playing in the Howard McGhee band, which often included Charlie Parker, whom he called his first and most lasting jazz influence. (Some of those performances were privately recorded and, with the piano solos cut, were issued on Mosaic as The Complete Dean Benedetti Recordings of Charlie Parker.) In the notes to Four!, Hawes writes: “I still love to play the blues, and the tunes I make up are still blues. But at one time I used to concentrate on them so much, I believe I neglected other things. These days (1958), though, I play even less notes in the blues, and maybe they’re getting to sound more like sanctified church music. That’s the sound I like to hear.” Not every pianist would be proud of playing fewer notes. It wasn’t a matter of a lack of technique, as he demonstrates on Four! in his ripping solo during “Like Someone in Love.”

Four! is one of his most satisfying sessions, for the variety of the repertoire and for the quality of the playing. It was recorded in the glory days of stereo when separating the channels was the thing. (On a late ’50s recording of Liszt etudes I own, the piano is spread across the sound stage: listening to a scale passage is like hearing a train steam by.) In this case, Hawes’s piano is in the left channel and the trio in the right — there’s nothing in between. It’s a peculiar setup but not bothersome; it even encourages you to pay attention to the deft way Hawes comps for the others. For years I have been listening to Four! on an OJC LP sent to me as a promo. (It has the ostensible price, $5.98, slapped across the cover.) To my ears, the sound is marginally more precise on the new Craft LP than on the generally unavailable OJC LP. The background is certainly quieter: I’d recommend the Craft for its sound as well as for the performances.

The session begins with Charlie Parker’s “Yardbird Suite.” After an introduction by the pianist, Kessel states the melody. In Hawes’s solo, we hear his flowing bop technique but also the subtle ways in which he breaks things up by holding a note here or there, or by finishing a phrase and letting a few beats go by before rushing onward. In one chorus, he pokes out isolated notes for a few bars. It’s these spaces that make his subsequent fluency so strikingly remarkable. His invented melodies are singable. On “Yardbird Suite,” Kessel takes over from Hawes, and then Mitchell. Red Mitchell was one of the most lyrical bassists around. (Listen to his “Blue Dove” with Jim Hall.) The tune ends after Hawes and Kessel cheerily exchange fours.

There’s an uptempo “There Will Never Be Another You” in which Kessel chunks away on rhythm guitar like Freddie Green while Manne keeps a whispering beat on brushes. The surprise number may be “Sweet Sue,” which was a hit for the Mills Brothers in 1932. There’s no Dixieland kitsch here. Mitchell’s short solo stands out. The session ends with “Love Is Just Around the Corner,” which Hampton opens with a lush solo introduction that includes some Tatum-esque runs, his only extravagant gestures of the session. Later the pianist claimed he had never played the tune before but found that, somehow, he had the right chords stashed in his memory. His was a remarkable talent. We should be grateful that Craft Records is doing such an honorable job reissuing Contemporary sessions. I look forward to others.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.