Visual Arts Review: “Matisse: The Red Studio” – A Lesson in Objects

By Melissa Rodman

Making the viewer draw visual connections among Matisse’s pieces in the title painting is at the core of MoMA’s The Red Studio.

Matisse: The Red Studio. On view at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City through September 10, 2022. Organized by Ann Temkin, The Marie-Josée and Henry Kravis Chief Curator of Painting and Sculpture, MoMA, and Dorthe Aagesen, Chief Curator and Senior Researcher, SMK, The National Gallery of Denmark in Copenhagen, with Madeleine Haddon, Curatorial Assistant, and Charlotte Barat, former Curatorial Assistant, MoMA.

“The Red Studio,” Henri Matisse;Issy-les-Moulineaux, fall 1911.Oil on canvas. Mrs. Simon Guggenheim Fund.© 2022 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Four quotations printed on the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)’s white corridor walls, leading to the main gallery, herald what’s to come: (1) “The whole is Venetian red.” (2) “This red, which is a little warmer than red ocher, is a precise color of the palette.” (3) “The painting is surprising at first sight. It is obviously new.” (4) “Have I told you that it represents my studio?” These punchy, propulsive snippets are from a letter that artist Henri Matisse wrote to his patron Sergei Ivanovich Shchukin in 1912, hoping to land the sale of “The Red Studio” (oil on canvas, 1911).

This striking painting, which Shchukin declined to purchase, anchors a new MoMA exhibition also called The Red Studio. Two enticing rooms tell the painting’s story — the first assembles the artworks depicted in the picture, which have not been seen together in more than a century; the second gathers blueprints, letters, photographs, and newspaper clippings that illustrate the painting’s winding path from Matisse’s studio in Issy-les-Moulineaux, on the outskirts of Paris, to several swanky London venues and New York’s famed 1913 Armory Show to a midtown Manhattan gallery and ultimately to MoMA’s collection in 1949.

“The Red Studio” catches your eye. Its deep brick red does not pervade the picture plane so much as this color creates, inhabits, is the space. Inside this studio-represented-on-canvas, pale, multicolored, almost ghostly outlines situate the artist’s furniture (two tables, a chair, some stools, a dresser, and a grandfather clock). Within the picture, bright paintings populate the walls and rest on the floor, giving the compressed room a subtle illusion of three-dimensionality. The eye links three small sculptures — two sinuous bodies; one bust, which, if you stare at it long enough, begins to resemble a torso — to the other figures featured in the paintings-within-the-painting. A royal blue silhouette of a fetal figure on a dish in the foreground echoes, and harmonizes with, these omnipresent human forms.

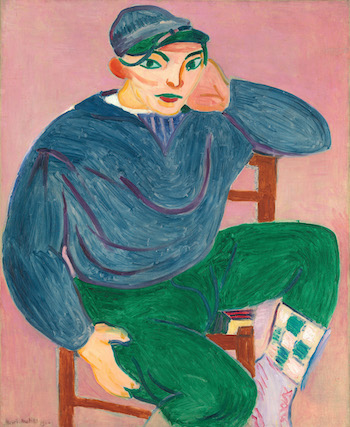

Henri Matisse. “Young Sailor II.” 1906. Oil on canvas. Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. © 2022 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Making the viewer draw visual connections among Matisse’s pieces is at the core of The Red Studio. With light-handed, unobtrusive curatorial touches, the first room encourages the viewer to wander around the works of art, seemingly plucked from Matisse’s canvas and dropped into the present: the terra cotta sculpture, the bronzes, even the dish — all displayed on generously spaced pedestals to enable 360-degree views — as well as the handful of paintings-within-the-painting mounted on MoMA’s walls. Together these works gain a certain depth, vivified because of their proximity to the titular painting. Likewise, the painting comes alive in the presence of the standalone pieces it depicts.

Consider the dish (“Female Nude,” tin-glazed earthenware, 1907). In “The Red Studio” painting, the plate is a flat, whitish disc with the quickly-brushed, sketchy fetal form at its center, surrounded by small yellow-and-blue blooms. Up close, though, the original earthenware piece sports hairline cracks; the flower design curves as the plate’s surface curves; and the principal figure sharpens, gaining fingers, toes, and a face.

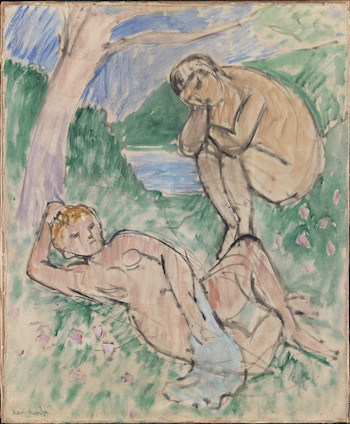

With a manageable number of objects to regard, the viewer gets to know them well. The central placement of “The Red Studio” painting facilitates a neat path: view half of the room — landing at its midpoint to linger in front of “The Red Studio,” to identify the first group of works you just have seen in the round — before proceeding toward the remainder of the pieces. A large painting in the latter group, “Le Luxe (II)” (distemper on canvas, 1907-08), stands out. It is another study of bodies, three nude women shaped with gray outlines. The hilly landscape behind them divides into thick bands, color-blocked in mauve, burnt sienna, and teal. Although the contents (hills, sky, bodies) are cordoned off and flattened, the thin, curvilinear outlining somehow counters the two-dimensionality.

In “The Red Studio” painting, Matisse replaced the warm beige skin tone of the “Le Luxe (II)” women with the ubiquitous Venetian red. A gallery label notes that “Le Luxe (II)” belongs to the “centuries-long tradition in European painting of depicting groups of figures relaxing in a natural setting” (a curatorial nod that made my mind jump to Édouard Manet’s “Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe,” 1863) and then adds, “During the early twentieth century, many avant-garde artists portrayed racial difference in a purposeful challenge to European ideals of beauty.”

The exhibition’s second room picks up this avant-garde storyline. Relocating from tight Parisian quarters, followed by a stint at two convents, Matisse envisioned a room of his own away from Paris, an affordable, utilitarian, light-filled space where he could embark on new work. Hiring the firm Compagnie des Constructions Démontables et Hygiéniques, he co-designed his 10-by-10-meter (33-by-33-foot) studio, whose meticulous blueprints are included in the exhibition’s assemblage.

Henri Matisse. Bathers. 1907. Oil on canvas,Gift of the Augustinus Foundation and the New Carlsberg Foundation. SMK – The National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen. © 2022 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In October 1912, “The Red Studio” first moved from Matisse’s studio to the Grafton Galleries in London, as part of the “Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition,” organized by Roger Fry, a member of the Bloomsbury literati. There — and at the February 1913 Armory Show in New York, which later traveled to Chicago and Boston — critics and the general public disdained Matisse’s work. “Matisse is dancing a wild tango on some weird barbarous shore,” critic Harriet Monroe, reporting from New York, opined in the Chicago Daily Tribune. “Matisse, in his ‘Panneau Rouge’ [‘Red Panel,’ i.e., what we now call ‘The Red Studio’] and one or two other pictures, throws figures and furniture on his canvas with precisely the prodigal impartiality and the reckless drawing of a child.” Needless to say, no one at the Armory Show purchased the painting.

But all was not lost. In 1927, “The Red Studio” courted a buyer, David Tennant, and found a home for a little more than a decade, hanging in the mirror-mosaic ballroom of Tennant’s London nightclub, the Gargoyle. Tennant ultimately consigned the painting to the Redfern Gallery, also in London, spurring a domino effect from Redfern to New York’s Bignou Gallery to MoMA.

It was — and is — at this last institution where “The Red Studio” received its due. “Every time I look at it, I get such sheer pleasure out of it that any other reaction comes as an afterthought,” MoMA trustee James Thrall Soby wrote in a December 1948 letter to the Committee on Museum Collections (a letter that, of course, is included in The Red Studio exhibition). “Let’s for heaven’s sake buy it.”

Melissa Rodman is a writer whose work also has appeared in Public Books, Bookforum, and The Harvard Crimson, among others.