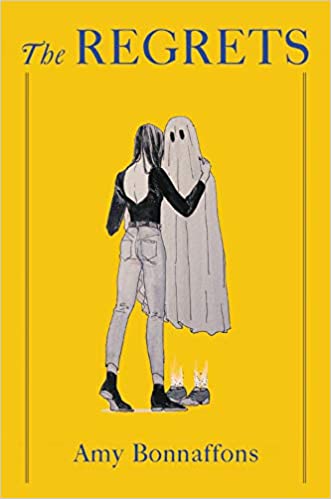

Book Review: “The Regrets” — Love Affair With the Semi-Dead

By Daniel Gewertz

Is Amy Bonnaffons saying that heterosexual love is doomed? Probably not. But she gives no indication it can work in the world she creates here.

The Regrets by Amy Bonnaffons (2020) Little, Brown & Co., 304 pages.

Is The Regrets

- a ghost story

- a zombie novel

- literary fiction/magic realism

- all of the above

The answer is D (yet The Regrets is still less than the sum of its imaginative parts.)

The center of this debut novel by Amy Bonnaffons is the love affair between an alienated female Brooklyn librarian and a sexy, sinewy mystery man who just happens to be both sublimely physical and, supernaturally, semi-dead. A lot of hunky hipsters in modern fiction disappear on their girlfriends. This one gradually develops airy holes in his body and then vanishes altogether.

The center of this debut novel by Amy Bonnaffons is the love affair between an alienated female Brooklyn librarian and a sexy, sinewy mystery man who just happens to be both sublimely physical and, supernaturally, semi-dead. A lot of hunky hipsters in modern fiction disappear on their girlfriends. This one gradually develops airy holes in his body and then vanishes altogether.

Thomas may be an undead, but he’s less “walking dead” than hailing-city-buses dead. He is not quite vampiric either — he doesn’t suck blood. But super-orgasmic sex with lithe librarian Rachel is eventually detrimental to her psychological well-being.

Pages could be written to fully describe the phantasmagorical setup of this freaky, elegantly written tale. The initial first-person narration belongs to Thomas, as he recounts the motorcycle crash that kills him and his best friend, Therese. But, as the bureaucrat of the afterlife informs him, a snafu has forced Thomas to keep on living for a two-month stretch. And Thomas immediately knows why, too. It seems that when he was 10, a female angel of death — an inept heavenly rookie with gorgeous wings but a bad sense of direction — had given Thomas a smooth black stone to swallow … a death-stone actually meant for the cancer-ridden kid down the block. Oops! So, two decades later, post–motorcycle crash, he is forced to live in a semi-dead state until the right paperwork comes through. Or something like that. While the highly detailed post-death mechanics are played as (forgive me) deadpan satire, Thomas’s childhood angel episode is written in lyrical, nearly sensuous wonderment. Yet his extreme guilt as a child, and his death-defying behavior afterward, is quizzical. (This black stone of death routine is apparently an obsession with Bonnaffans: she wrote a short version of this surreal swallowing trick in a story from her first book, The Wrong Heaven, in 2018.)

Once Bonnaffons gets down to describing the insular world of Brooklyn hipster singles, she’s witty and knowledgeable. Her prose is consistently inviting. She does utilize, with varying degrees of success, two trendy, patently impressive literary maneuvers: multiple first-person narrators and a female author narrating as a man. But her highest achievement is her ability to write astutely, emotively, and in non-obnoxious detail, about sex: a rare feat indeed. Since the whole book is suffused with alienation, the sex is not coupled with romantic love, exactly. But it is emotionally evocative.

Thomas’s narrative segments require some patience, though. We see him navigate countless post-death rules and regs in order to avoid being overtaken by “the regrets.” But his character remains elusive. He never thinks of avoiding his deadly fate, and the power of his guilt for killing his best friend isn’t well developed. (This may be a flaw of having such a cool customer be a first-person narrator.) The black stone of death is the book’s “creation myth,” but it’s too quirky to power the story. We travel with Thomas as he visits a hip coffeehouse and takes a specific Brooklyn bus to drop off required diary-like letters to the afterlife at a possibly magical mailbox. It isn’t until Rachel’s first narrative segment that the tale becomes grounded, and simultaneously, lifts off.

The Regrets features no heterosexual soul mates, or even lover-friends. So, by their absence, the novel paints a dismal picture of heterosexual couplehood. Thomas had a perfect soul mate in lesbian Therese. (She is his most piercing regret, since he got her killed.) Straight Rachel has a gay best friend to gossip with about their (separate) eccentric one-night stands. When, late in the novel, Rachel hooks up with a nice guy — a former collegiate lover who, for years, has pined for her — the relationship goes nowhere. Is Bonnaffons saying that heterosexual love is doomed? Probably not. But she gives no indication it can work in the world she creates here. At points late in the book, Rachel is surely spoiled by her (literally) scorching hot supernatural sex-capades. (“When I think of a regular lukewarm penis now, it seemed so boring, like an old, wet sock.”)

It isn’t hard to come up with real-life parallels to this paranormal plot. The search for the near-magical in love, the need to be overwhelmed, the way we fantasize a perfect love out of spare parts, the power of alienation to dissolve our lives: all those psychological parallels might be gleaned here. Yet The Regrets rarely harvests that fruit. The lengthy rules of Thomas’s semi-deadness fail to engage, and the scenes of Rachel’s startled inspection of disappearing Thomas (even sticking her whole arm through his vaporous torso) fall short of entrancement. As gorgeously written as the final sex scenes are, they didn’t make me lose my skepticism. (Maybe they’d work on a fantasy-lit fan.)

Some of the best parts of The Regrets are the realistic ones, such as Rachel’s ruminations about her cool yet somewhat lost Brooklyn buddies. The segment narrated by Mark — the college boyfriend still enamored of Rachel — is consistently strong. And the theme here is clear: even in nonmagical lives, we can be ruled by our obsessional romantic regrets. We invent “supernatural” creatures. The portrait of Rachel we gather from her own narration is a withdrawn, fearful, pale one. But Mark believes he’d been loved and left by a mysterious goddess. Rejection has transformed an elusive, insecure, pretty undergrad into a haunting ideal.

Despite the book’s title, regret doesn’t seem to be at the heart of the matter. We learn little about Rachel’s regrets, and the book’s conclusion seems forced. But Bonnaffons does weave something sublime at many points, and her voice is often good company: witty, sly, sophisticated. Her earlier book of short stories, The Wrong Heaven, falls way short of this novel. Engagingly quirky at first, it settles into sad, debased pathos, with most of the stories morosely perverse without any sense of illumination. That Bonnaffons’s writing deepened and improved so much in a few short years seems like a small miracle. Though not a supernatural one.

For 30 years, Daniel Gewertz wrote about music, theater and movies for the Boston Herald, among other periodicals. More recently, he’s published personal essays, taught memoir writing, and participated in the local storytelling scene. In the 1970s, at Boston University, he was best known for his Elvis Presley imitation.