Book Review: “Art and Faith” — Creating Revelatory Beauty

By Susanne Sklar

Art and Faith should be widely read — its delightful wisdom and clarity underlines our culture’s desperate need to make things new.

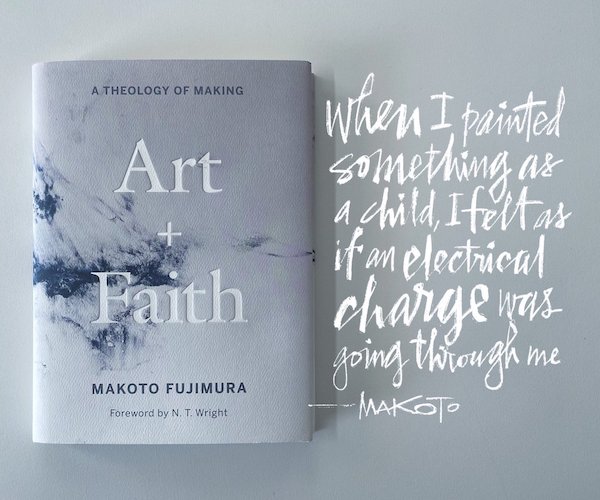

Art and Faith: A Theology of Making by Makoto Fujimura. Yale University Press, 184 pages, $26.

Buy at Bookshop

Art and Faith is a beautiful book. Anyone interested in social transformation, spirituality, or the arts will be enriched by carefully reading this collection of 10 luminous essays, written after the painter/author struggled with the trauma of working after 9/11. His home was near the edge of Ground Zero.

Makoto Fujimura (b. 1960 in Boston) studied in America as well as in Japan. His paintings combine abstract expressionism with what he calls the “ecosystem” of Japanese “Nihonga.” He works slowly, in accordance with ancient traditions and carefully prepared materials. For example, he reconstitutes oyster shells for a day and a half in order to make white paint, carefully calibrating its opacity and translucence. Preparing to paint, as it is for the creation of all art, is a spiritual practice. Themes of imagination, making, and beauty recur like musical leitmotifs in his essays.

Fujimura believes that God is the ultimate creator and that creating in the image of God is open to anyone, regardless of background, occupation, or social status. “Whether we are plumbers, garbage collectors, taxi drivers, or CEOs, we are called by the Great Artist to co-create,” he declares. Our lives are potential works of art. As for spirituality, imagination is at the heart of faith: Fujimura follows in the footsteps of one of his aesthetic mentors, poet and illustrator William Blake, who declared: “Jesus & his Apostles & Disciples were all Artists.” Of course, he isn’t writing only for Christians, or artists. God’s spirit is not interested in labels like “Christian” or “Church.” In fact, Fujimura classifies artists as “border stalkers” because they transcend “tribal norms” and mediate between conflicting realities. Beauty prepares the common ground upon which divided people may gather and heal. And that is one reason, among many, that Art and Faith is so important — our culture is in dire need of such healing.

If only our policy makers could read this book and be inspired, especially by the concept and practice of Kintsugi. What is broken can become more beautiful — when it is more than mended. Kintsugi (“kin”= gold / “tsugi”=reconnect) arose in 16th-century Japan, when a tea master prevented an attendant from being punished for breaking a precious piece of teaware. The master, Hosokawa, rejoined five broken pieces, using lacquer and gold to make the vessel lovelier than before. Kintsugi gold fills crevices, in the process creating something new. For Fujimura, all makers, particularly artists, have the duty to honor brokenness. Cracked and broken shards represent opportunities for renewal, a perspective that has powerful spiritual and social ramifications.

Fujimura also invokes the notion of a gift economy, a vision of exchange in which relationships are enhanced. He suggests, like Blake, that capitalism can be grounded in creativity. Work need not be dedicated solely to the useful and profitable, committed to empowering the competitive. It is meant to be inspired by the image of God; creative and compassionate, work is a way of spreading beauty and mercy.

Fujimura’s theology offers an alternative to our egotistical obsession with materiality. Christianity, he affirms, is not about fear, condemnation, intolerance, or exclusivity. It’s about making things new: “practicing Resurrection,” a practice in which all creative makers can “discover miracles every day,” even, and perhaps especially, when coping with suffering and loss.

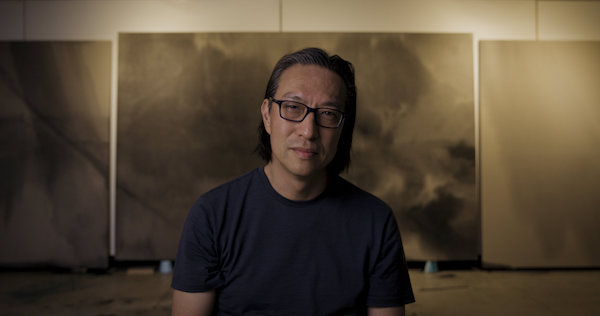

Painter Makoto Fujimura — “Simply put, when we make, God ‘shows up.'” Photo: Windrider Productions.

Our “cultural river runs with the tears of God,” Fujimura observes. He finds support for this belief in his readings of Western literature, such as T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, poems of “dislocation and synthesis.” Like Dostoyevsky, the author interprets the story of Lazarus as a metaphorical challenge to the living — he was raised after being dead for four days. We descend into darkness; we die in many ways; we lose. In the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi (“wabi”=poverty / “sabi”=rust) there’s beauty to be found in what is ruined or smashed. Destruction must generate more than the blockage of despair; it should engender deep compassion, “the pouring of gold into our fissures of brokenness.” That sympathy, like the tears of Jesus in the Lazarus story, doesn’t only restore life — it expands what we have lazily grown to see as life’s parameters, moving us beyond what Fujimura considers to be the trap of false dichotomies.

The author believes that we should all be searching for a “New Newness.” Original artists (and I would add scientists, too) discover or redefine what this “Newness” is. Fujimura anticipates such a paradigm shift through the acceptance of what he calls “Lazarus Culture,” which calls for the integration of the analytical and the intuitive. That kind of imaginative integration taps into the overflowing abundance of God: it is a revelatory beauty.

Fujimura rightly notes that the Book of Revelation is not about destroying the world; spiritual flames can refine us, as gold is refined by fire. Making art to the glory of God offers the possibility of moving beyond the worship of suffering. Apocalyptic visions clear the ground for New Creation. Art and Faith should be widely read — its delightful wisdom and clarity underlines our culture’s desperate need to make things new.

Susanne Sklar, a member of the Cumnor Fellowship in Oxford, is the author of Blake’s “Jerusalem” As Visionary Theatre (OUP, 2011). She writes and teaches at Oxford as well as Carthage College in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Her email: ssklar@carthage.edu.