Book Review: “The Movement” — The Struggle for Civil Rights, Abbreviated

By Jim Kates

The Movement works best as a stripped-down, high-speed introduction to the struggle for civil rights, nothing more.

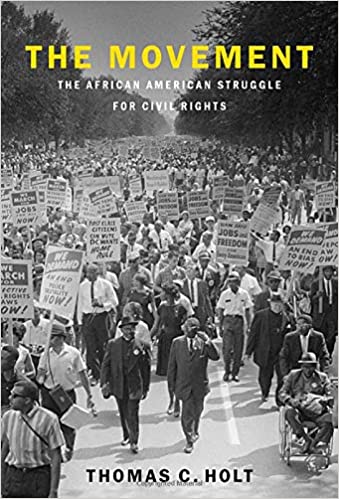

The Movement: The African American Struggle for Civil Rights by Thomas C. Holt. Oxford University Press, 176 pages, $18.95.

Buy at Bookshop

It is easy to see what’s missing from Thomas C. Holt’s overview of, in his book’s subtitle, “The African American Struggle for Civil Rights.” The Movement‘s one hundred twenty pages of pedestrian academic prose ends up rigorously stripping away its subject’s tumultuous emotional conflicts. The historian tries to cover more than a century of dramatic activity, with a special focus on the critical decade between 1954 and 1965. He’s bound to fail.

Yet he fails well. It’s the kind of an overview that might be submitted as a senior thesis by a student majoring in American history, and it can serve as a guidebook or an outline for any number of different fuller histories, perhaps culminating in Taylor Branch’s magisterial trilogy of America in the King Years. Nowadays our bookshelves groan with passionate memoirs and deeply researched histories and studies of civil-rights movements. Every February, documentary films with freedom-song titles are recycled. In this crowded context, The Movement works best as a stripped-down, high-speed introduction, nothing more.

And nothing less. Holt may be skating on the surface, but he skates widely and rapidly. To his credit, he does not overemphasize Dr. King. Instead, he keeps reminding the reader how deep in time and broad-based in leadership the Movement actually was. He begins with a quick survey of nineteenth-century attempts to desegregate transportation (curiously, there is no mention of slavery at all in the book) and then reports on the impetus that two World Wars gave to Black aspirations to equality. After this, he covers his crucial decade in a brisk and businesslike fashion. The bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham in September 1963 is put in its place:

Thus, a Movement launched in no small measure in response to the murder of a teenaged boy [Emmett Till] in the Mississippi Delta was confronted with yet another wanton slaughter of innocents. Whatever optimism the summer’s campaigns and national march had generated was deflated. An ostensibly New South city had turned its other face to the nation, one that echoed the terrorist campaigns of another time and place. In its aftermath — reinforced by future atrocities — the focus and the temper of the Movement would change. For many veterans of earlier struggles, their faith in the nation’s capacity to respond adequately to demonstrations of injustice faltered.

Holt sees 1968 as a punctuation mark. Whether it was a comma or a full stop is something activists and historians have been at odds about ever since. In his last chapters Holt expands his examination into the North, touching on the influence of “The Movement” on subsequent movements. But he clearly puts himself in the “full-stop” camp, even though he sees “the Movement” as “a different phase of a continuing struggle.” In real life, “the Movement” has evolved organically in time and place without interruption, mostly in local incarnations hardly recognized by general historians.

And, while The Movement ranges through the familiar landscape of Montgomery, Greensboro, the Albany demonstrations, Birmingham, Mississippi, and Chicago, there is no mention at all of critical activities in Florida, Louisiana, Arkansas, or other points west and north. Holt barely notices Europe and Africa in his centering on the most obvious American events and developments.

He does well to highlight the internal contradictions between a number of seemingly mutually exclusive goals: social integration versus Black self-sufficiency and empowerment; and the tensions of nonviolent philosophies and practices in the face of the need for self-defence. “Ironically” is a word Holt leans on heavily, varying it once with “paradoxically.”

But these are only spotlit moments: in the discussion of alternatives to nonviolence he does not even mention Robert Williams or the Deacons for Defense, and one essential book, Charles Cobb’s This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed, is mentioned only in a footnote.

Alas, the bibliography of recommended reading leaves out a great many essential references — both primary and secondary materials, Richard Rothstein’s study of Federal discrimination in housing, The Color of Law, for instance. (Many of the more personal and individual sources are available, for those who are interested, on the crmvet.org website, dedicated to preserving Movement accounts and history.)”Further Reading” is by far the weakest and least informative chapter of the whole book.

Holt’s most valuable point, which has been made more fully and eloquently elsewhere, but still bears repeating in its simplest form, is that “it is not exceptional leaders but ordinary people themselves, conscious of the historical possibilities of their moment and acting collectively, who have the capacity to . . . change their world.”

Amen, brother.

Jim Kates is a veteran of the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement, a contributor to the Mississippi State Museum of Civil Rights, and the editorial co-director of Zephyr Press, publisher of Letters from Mississippi, edited by Elizabeth Martínez.