Jazz Appreciation: A Celebration of Charlie Parker on His 100th Birthday

By J.R. Carroll, Steve Elman, Jon Garelick, Allen Michie, Steve Provizer, and Michael Ullman

Arts Fuse jazz critics offer their favorite performances from the Bird.

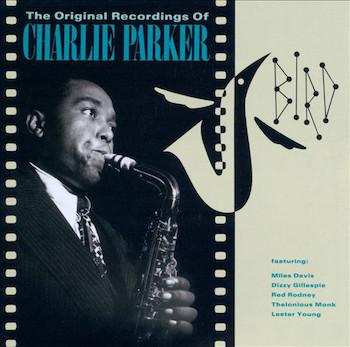

Charlie Parker in 1947. Photo: Wiki Commons.

Charlie “Bird” Parker was one of the greatest improvisers in any genre from any period on any instrument. Today, August 29, would have been his 100th birthday. In celebration, we invited our Arts Fuse jazz contributors to comment on some of their favorite Parker recordings. These are not necessarily the most canonical Parker “essentials” (although several of them are), but they are some of the performances that made our jazz critics fall in love with Bird’s music. We hope they’ll do the same for you.

Several performances came up more than once on the lists:

J.R. Carroll:

Even though from the beginnings of bebop Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker were joined in the minds of listeners, in point of fact they didn’t actually make all that many recordings and give that many performances together. So, when the Gillespie-Parker quintet reassembled (this time with John Lewis on piano, Al McKibbon on bass, and Joe Harris on drums) at Carnegie Hall on September 29, 1947, bebop fans flocked to the performance. They weren’t disappointed, as evidenced here and by Bird’s extended (and ferocious) solo on “Ko Ko.”

Charlie Parker: time to fall in love with Bird’s music — again.

Steve Elman:

So many of Bird’s live recordings are breathtaking in the execution but dreadful in the listening because of the limited tech capabilities of the time. This date fortunately has nearly everything in balance, and it seems to be a night of genuine camaraderie. You still have to endure the way-off-mic piano solos of poor John Lewis, but they give you a chance to breathe after you’ve thrilled to Diz and Bird in one of their greatest outings together (those dead spots even let you hear the two front men quietly plan how they are going to take the outchoruses). One of the many delights of the evening is the way in which Gillespie and Parker perfectly match their phrasing on every tune, even in the fiendish “Dizzy Atmosphere.” The session also has a furious revisit of “Ko Ko,” which is even faster than the original, but my choice here is “Confirmation,” one of the very few Bird tunes on original changes, a composition that shows obvious care and craft. It’s singable to boot, as Sheila Jordan has shown so well. Bird’s solo here sounds like he’s having a great time: in the first chorus, he feints at “At Sundown,” and in the second he flings in a bit o’ the highlands; but then he really digs in, and Dizzy’s vocal comments at the end of particular arpeggios show how closely he is listening. Gillespie knows Parker’s thinking well enough to follow Bird’s solo without a moment’s hesitation, keeping the energy at the same high level.

Allen Michie:

This one is on my list just because this song, and the solo, have been going through my head off and on for over 30 years. Parker isn’t jamming here – he takes a short and disciplined solo remarkable for both the clarity and ingenuity of its logic. It’s an example of Bird playing light, conversational, and happy. (Also, a word here in support of my fellow whistlers: I never had the chops to reproduce a Bird solo on alto sax, but I take comfort in being able to whistle some of them note for note, and “Yardbird Suite” is in this whistler’s permanent Top Ten. Try it yourself.)

Michael Ullman:

The melody is beautiful, and the entire solo is somehow more relaxed than is typical for Parker. The beginning of cool jazz?

Jon Garelick:

Lest we forget, Charlie Parker cut the Savoy and Dial sessions from 1945 to ’48 — changing jazz, and music, forever — while still in his 20s! Here is the master of extended harmonies in a relaxed mood on this 1948 Savoy date, improvising on a simple blues progression. A perfectly constructed lyrical outpouring, beginning with a clarion cry, it was set to words in a popular vocalese performance by King Pleasure in 1953.

Michael Ullman:

This is the quintessential blues performance by Parker. Dizzy said at the time that the beboppers didn’t play blues (nor did Sarah Vaughan sing them). Parker was one obvious exception, and Thelonious Monk was the other.

Steve Elman:

This contrafact of “Cherokee” remains one of the greatest jazz recordings of all time. Parker’s solo is a triumph of musical intellect, and it has been endlessly analyzed. But what I also savor here is Max Roach’s perfect support on drums, with a short break where he concentrates almost exclusively on his snare, showing how tiny fluctuations in tempo can make paradiddles into music – rather than the machine-gunning they can become in more ham-handed hands.

Michael Ullman:

This 1945 record is still astonishing. It should have been a disaster. Miles Davis, the trumpeter on the rest of the sides – the guy who was actually in the band – couldn’t play it. Dizzy Gillespie was there in the studio. There was no piano player, so Dizzy pounded out a few chords when he wasn’t playing that virtuoso introduction, half in unison and half improvised. And then with no statement of the theme, Parker just explodes into his solo. How shocking it must have seemed in 1945.

J.R. Carroll:

Charlie Parker flourished when challenged by a foil of the improvisational caliber of Dizzy Gillespie. Quite a few recordings survive of Bird’s regular quintet at the Royal Roost (introduced by the inimitable Symphony Sid Torin), but they can be frustratingly uneven. One factor may well have been that the trumpet chair was occupied by musicians still finding their own voices (Miles Davis and his replacement, Kenny Dorham). If Dizzy was the ultimate sparring partner for Bird, Fats Navarro came pretty damn close. For a May 17, 1950, gig at Birdland, Parker was joined by not only Navarro but the brilliant pianist Bud Powell, bassist Curley Russell, and up-and-coming drum powerhouse Art Blakey. Listen to Bird and Fats trading phrases on Denzil Best’s tune “Move” and imagine the possibilities if these occasions had been more frequent.

Steve Provizer:

What a lineup. This is one of the very few times that Bird trades fours with anybody – in this case, the great Fats Navarro. Astonishing playing all around.

Here are the other favorites from individual writers.

J.R. Carroll

Charlie Parker

While pulling together the tracks I wanted to include as my contribution to this ornithological celebration, it occurred to me that Charlie Parker was probably jazz’s last major figure of the 78 RPM era. Virtually all of his peers – Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, Charles Mingus, Max Roach, and many more – survived and flourished for years (and some cases decades) in the age of the long-playing vinyl record. Departed from our midst by 1955, Bird sadly never really had the opportunity to investigate the opportunities presented by the LP.

Filling in that gap are a host of live recordings (ranging from near-studio quality to pretty much unlistenable) that began to surface after Bird’s passing and have popped up with regularity during the subsequent 65 years. Here are a few tracks (and, really, entire albums) that demonstrate what Charlie Parker was capable of when offered a chance to stretch out at length. They only scratch the surface of the wealth of live recordings that he left behind. Even at the century mark, Bird’s full legacy is still being discovered.

Ironically, the first example comes from a performance that only came to light (and thence onto LPs and CDs) in the early years of this century. Long thought lost, the acetates of Dizzy Gillespie’s Town Hall concert were rescued from an Antiques Road Show fate, cleaned up, and released on the Uptown label. For this concert (June 22, 1945), Diz had assembled a group of all-stars: not only Bird, but also the underrated pianist Al Haig, the reliable bassist Curley Russell, and the young but already head-turning Max Roach on drums. Astoundingly, this same ensemble (minus Roach) had gone into the studio only six weeks previously to set down what were almost certainly the first genuine bebop sides. For folks who hadn’t heard those recordings, these white-hot performances must have left many a jaw on the floor of Town Hall—especially the stratospheric whoops by Bird and Diz coming out of Haig’s solo on “Salt Peanuts,” the likes of which weren’t heard again until John Coltrane’s Africa/Brass sessions.

A relatively frequent visitor during the final few years of his career, Charlie Parker seems to have genuinely enjoyed playing in Boston, at long-lost clubs like the Hi-Hat and Storyville. (For much more on these venues and the local bebop scene in the 1950s, consult Dick Vacca’s indispensable Boston Jazz Chronicles—see https://artsfuse.org/67021/fuse-book-review-the-boston-jazz-chronicles/.) A weeklong residency at the Hi-Hat Club in December 1952 reveals Bird in a more lyrical mode, spinning out long, thoughtful lines that span multiple choruses. Supporting him on the 1952 Hi-Hat tracks dates are Charles Mingus on bass and three Boston natives, the legendary and still-active drummer Roy Haynes and two gifted young Bostonians we lost all too soon, trumpeter Joe Gordon and pianist Dick Twardzik. All three—and, of course, Bird himself—can be heard to good advantage on “Scrapple from the Apple.”

Steve Elman

Charlie Parker’s recorded output is a collection of conundrums. How could so many seminal performances of the 20th century have so many flaws? Bird seems in a world of his own no matter what the context – always magnificent – but all around him are things that can get in the way of genuine enjoyment of any one track from beginning to end: unsympathetic support, slapdash recording, incongruous arrangements (especially in the Bird with Strings sessions) and artists of similar stature (like Dizzy Gillespie and Bud Powell) competing rather than cooperating toward a shared musical goal.

My choices here are inspired by one of Parker’s own descriptions of bebop philosophy: “looking for the pretty notes.”

Erroll Garner had a brief period of collaboration with Bird – there are live dates around the time of this recording (1947) on the West Coast – but all that remains to us are a couple of studio performances and a couple of sides with singer Earl Coleman. Unlike all the other pianists who played with Parker, Garner was a synthesist, drawing elements of his style from two-handed pianists like Earl Hines and Fats Waller, but modernizing his harmonic approach to fit a new musical era. His big chords underneath Parker in the theme are a delight, and they are just one element in a real meeting of the minds. After Parker’s elegant solo, Garner takes off with right-hand lines that are completely simpatico, but he then sneaks in some light left-hand comping that is unlike anyone else’s. The complete performance really tells a story.

This one is attributed to Parker, but Phil Schaap says it’s a combination of two French songs, “Le Petit Cireur Noir” and “Pedro Gomez.” It was producer Norman Granz’s idea to put Latin percussion behind Bird, and in this 1951 track, the experiment pays off. Parker sounds completely at ease, and his solo builds complexities on the very simple theme. Percussionists Luis Miranda and Jose Mangual are perfectly in sync; they achieve the feat of sounding active and relaxed at the same time, which complements Bird’s approach. The only flaw: Miranda and Mangual miss the closing note and just keep playing on into a fadeout.

This 1948 tune, a set of cheery overlapping phrases with Miles Davis’s trumpet taking the lead, is unusual because it avoids the unison setups from so many of Bird’s recordings. It’s also a fine example of a working Parker band in action. Bird has a full-chorus solo with textbook demonstrations of his distinctive phrasing – pausing exactly where you don’t expect him to. Davis and pianist John Lewis each have lyrical half-choruses that balance the leader’s complexities, and then Bird is back for a dense half-chorus that leads into bass and drum exchanges by Curly Russell and Max Roach.

So many of Parker’s contrafacts are built on “Cherokee” and “I Got Rhythm” that this one from 1946 must be noted – it’s built on the changes of Gershwin’s “’S Wonderful.” Bird simplifies the melody elegantly at first and then tosses in more and more complex phrasing as the tune goes along. He takes a full-chorus solo, especially rich in those pretty notes. All of his sidepeople are thinking in true bebop spirit, but each gets only a half-chorus because of the tyranny of the three-minute limit on 78 RPM releases. Howard McGhee has a typically fine trumpet solo with one small clam, Wardell Gray shines on tenor as brightly as Parker does on alto, we get a rare taste of the underappreciated pianist Dodo Marmarosa, and Barney Kessel has a nice spot on guitar. Bird misses his entrance on the improvised bridge in the last chorus, but the whole performance feels so friendly that we don’t mind.

Jon Garelick

“She Rote”

For me, Charlie Parker was not an immediate slam-dunk. I knew he was “important,” but I was getting into jazz via post-bop geniuses like Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, Charles Mingus, and Sonny Rollins. Besides, by this point (the early ’70s), Bird’s language was everywhere — so what made him stand out from avatars like Phil Woods or Charles McPherson? Also, as Steve Elman points out, the recording quality of Parker’s output was variable, with some of his most famous sessions sounding a bit pale. This track from 1951 gave me what I wanted: a big tone, bright and clear, an impossibly knotty bebop line played at high velocity, and a thrill-ride of blazing virtuosity.

Here is Parker in one of my favorite ballad performances by anybody. From George Gershwin’s melody and chord changes (and, maybe, in the back of his ear, Ira’s lyrics?), Bird fashions a new composition, contrasting dark and light upper and lower registers, and alternating tender in-tempo melodic phrases with exuberant double-time, all imbued with the freshness of spontaneous invention.

Allen Michie

My copy of this was on the Prestige album The Greatest Jazz Concert Ever, an all-star concert at Toronto’s Massey Hall with Bird, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, Max Roach, and Charles Mingus from May 15, 1953. That sounded like an album this jazz newcomer needed to have, and this was my first unfiltered dose of Bird outside of a few tracks on anthologies. The tightness, imagination, and facility of it all blew me away, and it still does. Bird’s solo has human cries, a quote from Bizet, lyricism in some passages balanced with flurries of quadruple-time phrases just afterwards, and perfect swing time—all of it rooted in the blues. I saw the white plastic saxophone Parker used in this concert on display at the American Jazz Museum in Kansas City, and I couldn’t stop staring at this holy relic.

Parker takes this already notoriously complex melody and breaks it down into phrases and fragments. He turns them sideways, upside down, reharmonizes them, puts them in random order, extends them, cuts them short, and connects them all intuitively with his own connecting tissues of invented melody. Of course it all fits in seamlessly with the chord changes, which are ticking by at one or two per measure. What went through the mind of the 21-year-old Miles Davis standing next to him while things like this are recorded, knowing he has to solo next?

There are several silly videos like this on YouTube, turning the friendly bop duel between Parker and Dizzy Gillespie (both in peak form) into a mimed argument. But it actually demonstrates how the phrasing of bebop, and much of improvised jazz generally, is still grounded in the qualities of the human voice. Parker and Gillespie together are always a source of wild creativity, with melodies begetting melodies begetting melodies. With all the attention to Bird’s genius, it’s easy sometimes to overlook the fun of it all.

Steve Provizer

Anything from this early 1951 session at Rockland Palace Dance Hall in New York, issued on Bird Is Free and other LPs over the years, is supreme. Bird and company stretch out in a live situation. The sound quality is mediocre, but the playing…

This is earlyish Bird, when he had done very little studio recording. “Red Cross” is from a Tiny Grimes session recorded on Sept. 15, 1944. There are succinct, perfect statements by Bird and guitarist Grimes.

Michael Ullman

I am restricting myself to Parker’s legitimate studio recordings. Otherwise I might include that late-night performance of “Cheryl” in which Parker spontaneously quotes the entire solo introduction to Louis Armstrong’s “West End Blues,” and then goes on as if nothing happened.

Parker is in front of thin-sounding strings, but the music flows out of him. I remember hearing for the first time all the takes of an awful arrangement by Gil Evans for Verve of “In the Still of the Night.” There’s complicated writing for winds, and then the dorkiest small singing group. It could have been from the Perry Como show. Again and again they start off in a different tempo from the band. Evans gradually took out his wind parts which only cluttered up the background. At some point, after boycotting the first takes, Parker starts to solo. Even on takes that were completely unusable, he soars. Again and again, the music just pours out of him. I get that feeling from “Just Friends.” There was no end to the riches in that man’s musical soul.

Thanks to Allen Michie for coming up with the idea, and for compiling all the material from the Arts Fuse‘s tremendous jazz critic lineup. — Editor Bill Marx

Tagged: Charlie-Parker, James Carroll, Jon Garelick, Michael Ullman, Steve Ellman

‘He’ll make your head explode’: sax stars on the genius and tragedy of Charlie Parker

(Including the day Beyoncé got introduced to Bird!

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2020/nov/18/head-explode-sax-stars-genius-tragedy-charlie-parker?CMP=share_btn_fb&fbclid=IwAR2JF2mxL-2_Kzr6v3D_sRDsSilwa9OAVc01UCj5NKIDNO1d-n5iSHpjHEw