Book Review: “The Glass Hotel” — Not Transparent Enough

By Matt Hanson

One of the pleasures of The Glass Hotel is how easily digestible it is; the prose rolls off the page, rewarding the reader’s close attention with subtle insights into character and motivation.

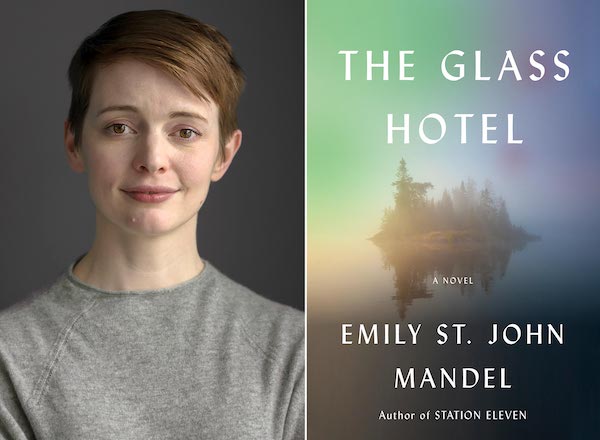

The Glass Hotel by Emily St. John Mandel. Knopf, 320 pages, $26.95.

Emily St. John Mandel must have some kind of crystal ball. Her 2014 novel Station Eleven was a critically lauded bestseller and recently garnered relevance given its prescient premise — a group of traveling actors try to survive amid a deadly global pandemic. It’s been widely recommended on literary websites for consultation among the vast number of people who are now stuck indoors. Her new novel, The Glass Hotel, explores a separate but apocalyptically related issue which may well be looming on the already fraught socio-political horizon: financial catastrophe.

We are introduced to the brother and sister pair of Paul and his oddly named sister Vincent, who find themselves connected in different ways to the millionaire investor Jonathan Alkaitis. Paul is a sensitive loner, a wannabe avant-garde musician drifting through the University of Toronto. A random encounter with bad drugs leads him astray, which leads him to take a sympathy job at the titular hotel, owned by Alkaitis, where Vincent bartends. One night a mysterious message is found written across one of the hotel’s walls: why don’t you swallow broken glass. This act of surreal vandalism turns too many of the plot’s wheels to go into. Suffice it to say that sentiment isn’t just a random bit of snotty graffiti — it has implications that go back years and these will have dire consequences for all involved.

One of the pleasures of The Glass Hotel is how easily digestible it is; the prose rolls off the page, rewarding the reader’s close attention with subtle insights into character and motivation. By the end the various threads of the plot resolve themselves rather elegantly. Lots of distinguished contemporary fiction sets out to be jagged, experimental — form and function are pushed to the very limit. In contrast, Mandel writes with a soothing clarity as well as a deep attention to pacing. Her eye for characterization is sure, thorough, and nuanced. It would be easy (to the point of being clichéd) to reduce the Vincent and Jonathan relationship to that of a billionaire and his human toy. But the strong-willed Vincent is depicted as a rather complacent kept woman who is fully aware of the peculiarity of their relationship. There’s a genuine affection between the two. Jonathan could easily be written as a Gordon Gecko–style corporate shark, but he’s much less full of himself than characters in his well-heeled position might otherwise be.

Mandel picks up on some of the ways in which money affects our psyches: Jonathan “carried himself with the tedious confidence of all people with money, that breezy assumption that no serious harm could come to him.” An arrogant artist tries way too hard to balance his sloppy clothes with his agile handling of a cigarette. Another character, an older woman who used to make the scene in ’50s New York, wisely reflects that “beauty can have a corrosive effect on character. It is possible to coast for some years on no more than a few polished lines and a dazzling smile, and those years were formative.”

The business people affiliated with Alkaitis’s Ponzi scheme are given their individual difference, but they share a common trait — willful negligence. As one of them puts it in a deposition, “it’s possible to both know and not know something.” Sure, it’s easy to love your dirty money when it pays for all the things you both want and need. The catch is that the more embedded you become in that elite, hermetic world the less real your daily financial transactions feel.

But it is on this point that Mandel’s otherwise smooth narrative hits a major snag. Through the course of The Glass Hotel its characters become far more than walking statements about wealth and entitlement. Alkaitis made his money via a Bernie Madoff–like Ponzi scheme, draining an exponentially growing number of people’s bank accounts. He is handed a life sentence, where he lies in prison dreaming of a “counterlife” (shades of Philip Roth) where he didn’t get caught and is invited to glide around the UAE all day, savoring the air conditioning. What we don’t learn very much about is how his plan worked for as long as it did and how it was put into motion in the first place. It’s important for readers to understand how financial manipulations go down in the real world; it’s not enough to gesture toward the machinations of scams obliquely, leaning too heavily on fictional license. We’ve all seen the havoc wreaked by high-end cons on national and global economies. In many ways we’re still recovering from the old crimes as new rip-offs approach. It behooves novelists who want to write penetratingly about how financial schemes are savaging humanity and the environment to take us inside, to show us how we are being fleeced.

The luxury of omitting the nitty-gritty of lucre, of refusing to Xray the (sometimes legal) skullduggery corporate raiders use to live off the fat of the land, has passed. It’s vital, in fiction about the admittedly tricky and often dismal subject of economics, that our noses be rubbed in the ways that big money is made in today’s world of increasing scarcity. Otherwise, the narrative may gleam like polished glass — but it isn’t transparent.

Matt Hanson is a contributing editor at the Arts Fuse whose work has also appeared in American Interest, Baffler, Guardian, Millions, New Yorker, Smart Set, and elsewhere. A longtime resident of Boston, he now lives in New Orleans.