Jazz Album Review: Christian McBride’s “The Movement Revisited” — Continuing the Struggle for Civil Rights

By Michael Ullman

In this disc dedicated to black heroes of the Civil Rights Movement, Christian McBride insists that everyone must be free if any of us is going to be.

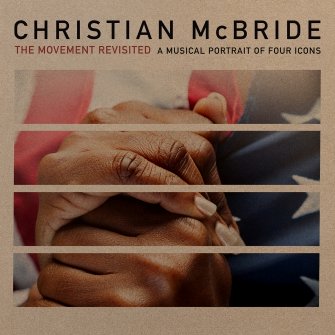

Christian McBride, The Movement Revisited: A Musical Portrait of Four Icons. (Mack Avenue)

This is rare: bassist/composer Christian McBride’s album notes, their combination of humility and wisdom, are almost as fascinating as the disc’s music and texts. McBride explains that his composition, dedicated to Rosa Parks, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, and Muhammad Ali, has been presented in several forms and instrumentations, beginning in 1998 when the bassist received the commission from the Portland Maine Arts Society. His initial conception was to create a “musical portrait of the Civil Rights movement.” He adds: “It never occurred to me that some viewed the radicalism of the Nation of Islam as NOT being a part of the Civil Rights movement.” Here’s where McBride’s humility comes in: “No longer wanting to offend my elders by wrongly suggesting I passionately knew the nuts and bolts of the Civil Rights movement, I decided to call this piece of music what it actually is — simply a musical portrait of four icons that touched me deeply on a personal level.”

This is rare: bassist/composer Christian McBride’s album notes, their combination of humility and wisdom, are almost as fascinating as the disc’s music and texts. McBride explains that his composition, dedicated to Rosa Parks, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, and Muhammad Ali, has been presented in several forms and instrumentations, beginning in 1998 when the bassist received the commission from the Portland Maine Arts Society. His initial conception was to create a “musical portrait of the Civil Rights movement.” He adds: “It never occurred to me that some viewed the radicalism of the Nation of Islam as NOT being a part of the Civil Rights movement.” Here’s where McBride’s humility comes in: “No longer wanting to offend my elders by wrongly suggesting I passionately knew the nuts and bolts of the Civil Rights movement, I decided to call this piece of music what it actually is — simply a musical portrait of four icons that touched me deeply on a personal level.”

That’s not all the trouble he had with his elders. For a 2013 performance of this work at the University of Maryland, Civil Rights icon Harry Belafonte read the words of his friend Martin Luther King. Afterwards, McBride asked Belafonte, who had started off as a jazz singer before finding calypso, what he thought of the music. Belafonte didn’t approve, criticizing the music’s contradictory shifts. He was disturbed by what he saw as the “‘jagged’ shifts in musical mood, the move from ‘Brother Malcolm’ to the loud, playful, funky section dedicated to Muhammad Ali (‘Rumble in the Jungle’), then the turn to the somber, reflective homage to MLK in ‘Soldiers (I Have a Dream).'”

Musically, McBride stuck to his guns. I am guessing most listeners (I’m an elder too) will understand and even approve. Muhammad Ali’s exuberance, the at times humorous way he defied racist stereotypes while also putting his life, to say nothing of his profession, on the line, differs from the somberly uplifting speeches of Martin Luther King, the sublimely self-contained statements of Rosa Parks, and the thoughtful ruminations of Malcolm X. The music should reflect these different — but all defiant — strategies. I am reminded of something Duke Ellington said when hearing a dissonant chord: “That’s the Negro’s life!… Dissonance is our way of life in America. We are something apart, yet an integral part.”

The chosen texts stress ecumenical messages, and are read by poet Sonia Sanchez and actors Vondie Curtis-Hall, Dion Graham, and Wendell Pierce over music provided by a big band and choir. McBride’s overarching message: everyone must be free if any of us is going to be. The beautiful, intense ballad melody of “Brother Malcolm” is first played by tenor saxophone (I believe it’s Ron Blake) over McBride’s agile bass. The ensuing vocal asserts that “Brother Malcolm fought for freedom for us all.” Interestingly the music becomes freer, and more ambiguous, after this assertion as Geoffrey Keezer’s piano plays in and around the impassive statements of the lead saxophone.

The moving blues of “Sister Rose” dramatizes the arrest of Rosa Parks over a flute obbligato by Steve Wilson The rambunctious “Rumble in the Jungle” unfolds over a jumping bass line by McBride and baritone saxophonist Carl Maraghi. Later, the saxophone section trades solos. “Soldier (I Have a Dream)” begins solemnly enough, featuring a march rhythm on drums and McBride’s bass monotone. Then Dion Graham performs King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. It’s a difficult challenge: Graham doesn’t dare to attempt King’s rhetorical agility and power. So he comes off sounding somber rather than inspired. But his words lead into the gospel song, “A View from the Mountaintop” (“Thank you for your vision”). J.D. Steele, who is also the choral arranger, sings “You saw the world together as one.” The tune eventually becomes rocking. The suite ends with Apotheosis, in which all the readers give us the uplifting (but unannounced) words of Barack Obama from his “Yes, we can” speech. This piece includes a glorious trumpet fanfare that gradually fades away, as if overcome with doubt. The overall message is hopeful, because the tune celebrates a victory due, in part, to voters who had never voted before. And in that election Americans expressed confidence that progress had been made toward a society that is based on common beliefs and historical awareness. But it’s clear, as Parks always said, that there’s still work to do. That work is what McBride is trying to do, I believe, with The Movement Revisited.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for The Atlantic Monthly, The New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, The Boston Phoenix, The Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.