Book Review: “Experiments with Empire” — Ways to Re-envision the World

By Emilie de Brigard

Experiments with Empire makes some perceptive points about how the connections between ethnography and fiction can help us reimagine the world.

Experiments with Empire: Anthropology and Fiction in the French Atlantic by Justin Izzo. Duke University Press, 282 pages, $25.95.

Justin Izzo, an assistant professor of French Studies at Brown University, has come up with a provocative book-length series of thought experiments that focus on our understanding of the French Atlantic region. His goal is to make “connections between different ways of knowing the world,” an approach that owes much to French anthropologist and filmmaker Jean Rouch, whom he cites in the introduction. Rouch’s admirable project was “the creation of fiction beginning from the real.” Izzo wants to carry on this mission, to make us “think critically about social-scientific and literary ways of knowing the world,” urging us to imagine “new ways of world knowing by rearranging the geographies and histories of imperial social forms.” Yes, the book is filled with the heavy-duty language of postcolonial studies, but Experiments with Empire deserves an audience beyond the academic. Izzo makes some perceptive points about how seeing the connections between ethnography and fiction can help us reimagine the world through a discussion of the work of nine 20th-century authors working in French West Africa, the Caribbean, and Marseille.

The volume begins and ends in France. In 1931, Michel Leiris sailed from Marseille as the secretary-archivist of the Mission Dakar-Djibouti, the first major state-sponsored African ethnographic expedition. During the trip, Leiris — an unclassifiable writer who had broken away from the Surrealists — compiled a personal journal, published in 1934 under the title Phantom Africa. Its unruly tone diverged wildly from that of the scientific publications by Marcel Griaule, the father of French anthropology. There’s an echo of Evelyn Waugh’s venomous modernism in Leiris: “What I will never forgive the Abyssinians for is having managed to make me recognize that there is some good in the colonies.”

At the same time, a young Malian scholar, Amadou Hampaté Ba, was beginning his career in the French colonial service. He toiled as an obscure clerk while privately collecting material on oral traditions that would become a treasure of African cultural heritage. Hampaté Ba’s memoir of that time, Oui mon commandant!, exposes the patronizing behavior of the colonial officers under whom he served.

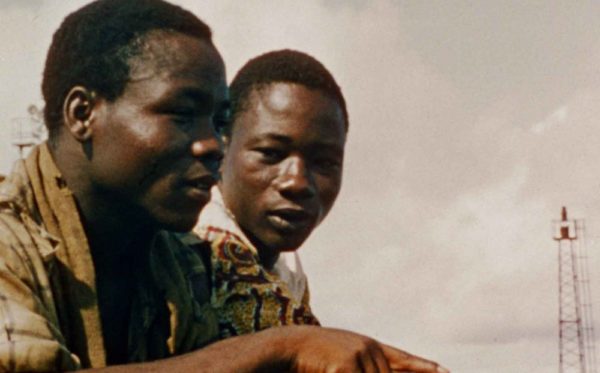

The book’s most substantial chapter dealing with Africa is about Rouch, the legendary filmmaker and anthropologist who created cinéma-vérité at the time of the French New Wave. Izzo gets Rouch half-right, which is better than many who try to wrap their minds around his accomplishments. Rouch’s MO was confusion — his beau ideal was the Pale Fox of Dogon cosmology, who sows disorder for the sake of creativity. The chapter on Rouch’s “ethno-fiction” zeroes in on three early films: Jaguar (1967), Moi, un Noir (1958), and La pyramide humaine (1961). Izzo’s detailed description of Moi, un Noir’s continuing power is welcome. (The movie is on many international critics’ 10-best film lists). Rouch made Moi, un Noir while doing contract research in Ivory Coast, casting his Nigerien research assistant, Oumarou Ganda, as an African veteran of the Indo-China war. The slight plot chronicles the hero’s hard life in Abidjan, where he works on the docks by day and drinks in bars in Treichville at night. Lighthearted fooling turns toward deeply emotional confession when Ganda, at the close of Moi, un Noir, delivers a searing monologue about his life.

While Isso places Moi, un Noir in the context of Rouch’s other fiction films, he doesn’t draw on what he calls Rouch’s “documentaries” and ignores his cine-portraits. That neglect can be forgiven; more damaging is that he skimps on Rouch’s influences, particularly Italian neorealism. That matters because Rouch wasn’t just responding to the situation on the ground in West Africa — he brought a French reverence for Greece and Rome to everything he did. Still, Izzo is right to see Rouch as a pioneering “director of modern life.” Ironically, his work isn’t as well known as that of Jean-Luc Godard, though Rouch had a direct impact on that director as well as, indirectly, distant descendants in Reality TV.

A scene from Jean Rouch’s Moi, un Noir.

Two fascinating, dense chapters on the Caribbean take up transatlantic conversations, cross-pollinations, and remixes. Izzo is less interested in providing background on the authors themselves than in teasing out the ideas behind writings that bear witness to Haitian nation-building and Martinican créolité. The selected authors from Haiti: the doctor and diplomat Jean Price-Mars; the tragic Jacques-Stephen Alexis (who at the age of 39 was “disappeared” by the paramilitary Macoute); the nomadic Communist activist and “banyan man” René Depestre, now retired in the French countryside; and Canadian exile Dany Laferrière, who has since 2015 occupied Seat 2 of the Académie Française. The Martinican authors are Raphaël Confiant and Patrick Chamoiseau, both tireless experimenters with language and genre. The diversity of genres that Izzo examines shouldn’t be surprising: these irrepressible authors of métissage take up allegory, negritude, zombisme, and much more, producing poems, novels, screenplays, and comic books in addition to dissertations, journalism, and polemics.

Izzo’s final chapter is a surprise, given its subject, the Marseille-based crime writer Jean-Claude Izzo (no relation). If the previous writers in Experiments with Empire were ethnographers who incorporated fiction, Izzo is a novelist who became an experimental ethnographer. The study uncovers the presence of idealistic musings in Izzo’s speculative cityscapes; his Marseille is a city “halfway between tragedy and enlightenment.” His protagonist, the disillusioned Fabio Montale, calls the metropolis “the only utopia in the world.”

The experiments of Rouch, and the other authors discussed here, help us make sense of the complicated legacies of empire. But will they be of use in dreaming up new democratic futures? The book doesn’t convince on this point. Although Rouch was certainly on the side of the African, he was neither a political artist nor a futurist of any stripe. His lifetime project was to create a cine-portrait of Dongo, the Songhay god of thunder. Rouch was at his most serious contemplating the forces of nature. Still, there is much that is valuable in Experiments with Empire as it explores the intersections of ethnography and fiction. Also, the book’s bibliography is excellent; it will provide an indispensable reading list for years to come.

Emilie de Brigard produced Jean Rouch’s only American film, Margaret Mead: A Portrait by a Friend.