Visual Arts Review: “In the Vanguard” – Haystack’s First Twenty Years

By David D’Arcy

Contemporary crafts in those days would have been seen as far from the ‘vanguard’ by many art critics. Yet the almost 100 works on view tell a nuanced story about the expansive spectrum of creativity.

In the Vanguard – Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, 1950-1969 at the Portland Museum of Art, Portland, ME, through September 8. The show moves to the Cranbrook Art Museum in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, from November 15 to March 8, 2020. (The exhibition catalogue, written by M. Rachael Arauz and Diana Jocelyn Greenwold, is available from the University of California Press.)

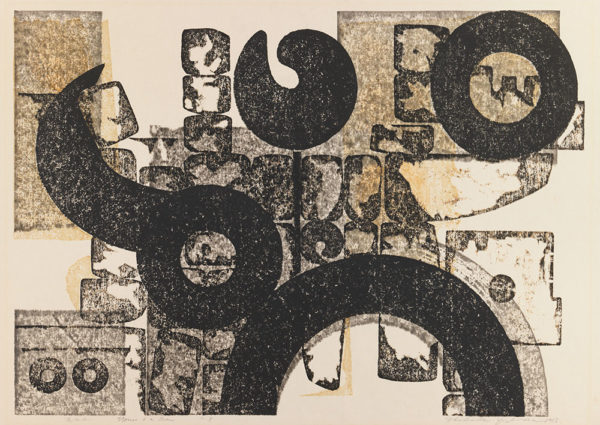

Hadaka Yoshida, “Stones and a Man,” 1956. Relief print on paper. Photo: courtesy of the Portland Museum of Art.

If you’ve visited the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts you probably haven’t forgotten it. Atop a granite hillside at the extreme end of Deer Isle, Maine, on the eastern edge of Penobscot Bay, you pass through a portal of wood that takes you to a sublime view of islands and sea. That’s just the beginning.

Wide wooden staircases lead down to a spread of sheer rocks, where the water rises at high tide. At right angles off that walkway, shed-like studios sit on decks made of wooden boards. The noise of machinery from these structures suggest that the school’s artists are in the midst of creation.

“Shed” understates the site’s ingenious design, built in 1961 by the architect Edward Larrabee Barnes. Scaffolding attaches the bottom of these sheds to the stone surface, balancing these structures on rocks and moss — they sit where building anything would seem unthinkable.

Like it or not, Haystack is as defined by its extraordinary architecture as is New York’s Guggenheim Museum.

Venerated today as a school as well as for its architecture, Haystack started off far more modestly. The exhibition In the Vanguard – Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, 1950-1969 looks at the productions of Haystack’s artists (craftspeople seems to undervalue them) from around the time of the school’s beginnings in the backwoods of Montville, Maine. Try finding that town on a map.

Contemporary crafts in those days would have been seen as far from the ‘vanguard’ by many art critics. Yet the almost 100 works on view tell a nuanced story about the expansive spectrum of creativity. Many of the pieces take you to a point where art and craft are indistinguishable. Perhaps this is what the Hawaiian-born potter Toshiko Takaezu, an early teacher at Haystack, had in mind when she stated her craft mission — “no ashtrays, no souvenirs.” It’s another way of saying, “gallery, not gift shop.”

When you enter the show on the ground floor of the Portland Museum, some objects on view seem to be reaching back toward pre-history. Ceramic works suggest the surfaces of fossils. A 1958 double-spouted vase by Takaezu (now in the Cranbrook Art Museum collection), has the iconic look of a creature with two faces, or two bellies, or an early ancestor of such a grotesque creature.

Dorian Zachai, “Allegory of Three Men,” 1962-65. Wool, silk, rayon, wood, cotton, ceramic, metallic threads, and dacron stuffing. Photo: Portland Museum of Art.

An upright candelabra by Mary Beasom Bishop, a philanthropist who helped found the school, stands with the skeletal chutzpah of an archaeologically excavated animal.

Summer art pilgrimages to Maine date from the late 19th century. They were followed by summer art encampments. Haystack was a latecomer, but it was distinctive because it focused on crafts, rather than fine art.

In the Portland museum galleries, the generous selection of objects — pottery, jewelry, textiles — would seen to be a world away from the grand abstractions of Jackson Pollock and company that dominated American painting and sculpture in the ’50s. Yet in the earthiness of the ceramics there are similarities to the paintings of the French artist Jean Dubuffet. Toshiko Takaezu and Dubuffet both seem to be after the same thing: expressing materiality at its most essential. An earthy zen was in the zeitgeist.

Yet, zen wasn’t for everyone at Haystack then. The patterns on Jack Lenor Larsen’s textiles, who taught at the school from its beginning, are nothing if not abstract. The vibrancy of his colors still radiate out six decades later. Painters at the time were determined to unleash color and energy (some abstract painters taught at Haystack in those early years), yet with Larsen you get the feeling that his mission was to tame those forces, by making them feel somehow weightless. At 94, he continues to monetize his work as a textile designer, as he has for the last 70 years.

If Larsen is one of the show’s bona fide celebrities, another is Dale Chihuly, known for his flamboyant, overflowing arrangements of colored glass. (The artist had a massive show at the MFA Boston in spring/summer 2011.) Chihuly taught at Haystack for four summers in the late ’60s. His muted, to the point of eerie, “Wine Bottle” (1968) features a tubular antenna spiraling out from a sphere tinged with goldish-brown — it comes from a time before the artist became a global crowd-pleaser. As a bio-morphic work, it’s more “alien” than it is abstract, a rare example of Chihuly eschewing bright colors.

Haystack moved to its grand Deer Isle site in 1961, when the state of Maine cleaved a highway through its Montville property. The move coincided with an expansion of the field of studio crafts.

Glass became a medium for a new generation of artists like Chihuly and for Harvey Littleton, whose “Bottle” (1965) is a study in paradoxes – a solid sculpture that seems to be dissolving as it absorbs light. Were it made of a material other than glass, the work might have drawn more critical attention. But then it would not have been the same work of art.

On the adjoining wall, just before the exit, is “Celibacy,” a weaving in red from 1968 by Walter Nottingham that looks like Pop Art fashioned out of fabric. Arranged as a corsage of crimson out of which tendrils bleed downward, the bold work, thanks to its cryptic title, invites all sorts of interpretations.

Sam Herman, vase. Photo: Portland Museum of Art.

Whimsy veils the edginess of a standout work, a 1959 film by Stan Vanderbeek called “Looney Spoons,” not to be confused with the successful cookbook of the same name.

Vanderbeek (1927-84) takes cheap table utensils and bends them into birdlike forms, though the figures are human enough to mimic dancing and fighting. His five-minute film, shown on a screen above two erect creatures made out of cutlery, is an exercise in the choreography of the primal, a buffo ballet that is as elegant as it is humble.

Critics might note that the sculptor Alexander Calder and the surrealists filmed their figures made out of bent metal and other ordinary materials. But somehow Vanderbeek brought the camera closer, lit the “action” dramatically, and edited the performances to make you laugh once you get over the logistical illogic of utensils in battle or at play. Look closer, and you might see that Vanderbeek’s figures resemble one of the stars of Toy Story 4, a character called Sporky, who is made out of a plastic fork-spoon and a pipe-cleaner.

Ultimately, “Looney Spoons” takes us back to the joys of crafts: completing a task with the simplest materials at hand, or making simple objects beautiful, or just creating beauty. Or making toys — and letting them dance.

David D’Arcy, who lives in New York, is a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He reviews films for Screen International. His film blog, Outtakes, is at artinfo.com. He writes about art for many publications, including The Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary, Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at The Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

Tagged: Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, In the Vanguard – Haystack Mountain School of Crafts