The Fuse in London: Jazz Festival, Diary 3

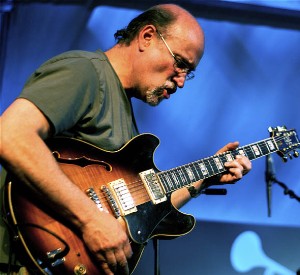

But on to the bliss of the first half, and I don’t use the word “bliss” lightly. In every respect, John Scofield, Steve Swallow, and Bill Stewart are one of the most cohesive units in jazz, and their hour together was superb.

By Steve Elman.

John Scofield was the headliner last night, but it seems right to start with the drummers. Sco has been very careful in his choice of percussionists—he’s had long associations with Adam Nussbaum and Bill Stewart, tapped Adam Deitch for his jam band, and calls on Ricky Fataar or Johnny Vidacovich to get that New Orleans groove.

But drummers beware: Scofield’s distinctive phrasing requires careful attention and a flexible approach to time. That’s one of the reasons Bill Stewart is such a congenial partner (20 years on) in Sco’s trio of choice. In last night’s double-barreled showcase at the Southbank Centre’s Queen Elizabeth Hall, Stewart showed once again why he’s crucial to the Scofield trio’s music and (as you would expect) offered an object lesson in accompaniment for Alyn Cosker, the veteran Scots drummer who anchors the Scottish National Jazz Orchestra (SNJO).

Not that Cosker is a slouch. His time is strong, his tuning mellifluous, and he’s got power to spare. But when you drive a big band, you have to pump out the decibels and keep the beat firmly in place. That isn’t necessarily the best way to play behind Scofield. So the first half of the program, which ended a Scofield- Stewart-Steve Swallow blitztour of European venues (they had previously played 27 dates in 32 days), was exquisite, and the second, with the SNJO, not quite.

Let’s work backwards. The SNJO, led by tenor saxophonist Tommy Smith, is formidable. On the previous night, they played their own adaptation of George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” with Brian Kellock at the piano, and then worked through repertoire associated with Woody Herman’s band. Tonight, they accompany vibraphonist Gary Burton. This band has range and ambition.

Behind Scofield, their execution was sharp. Trumpeter Ryan Quigley was articulate and convincing in his solo in Mike Abene’s arrangement of Marcus Miller’s “Tutu.” In his tenor solos, leader Tommy Smith showed off impressive chops and a mastery of the post-Coltrane harmonic landscape. The other players seem to handle difficult writing with aplomb, and they respond immediately to head cues or quick, come-on-in gestures, a skill that speaks to their group dynamic.

But it’s hard for their rhythm players to measure up to the standards set by Scofield’s regular team. Under John’s solos, pianist Steve Hamilton may have been a little too assertive, though his support for Smith was exactly right. Bassist Calum Gourlay handles his instrument well, but there can only be one Steve Swallow. Alyn Cosker got several solo spots, and, especially over the vamp in Michael Gibbs’s arrangement of Scofield’s “Groove Elation,” he took some big risks playing against the beat, with good results; still, if they had let Stewart sit in . . .

No complaints, though, about the performances of Miles Davis’s “Splatch” (in an arrangement by Fred Sturm) or the encore, Geoff Keezer’s arrangement of Sco’s “Green Tea.” Everything came together well in these two, and we also got a nice taste of Smith’s flute work.

The vibes on stage were sweet. When Smith mentioned the Woody Herman show on the previous night and indicated that Sco’s music is a bit out of the ordinary for his band, John brightened immediately and offered to play their chart of “Woodchopper’s Ball.” It almost happened—except for the fact that the arrangement happens to be in an uncongenial key for guitar and, as John said, “I left my capos at home.”

And now, in keeping with the motto of The Arts Fuse, I have sharpened my pen a bit. The great disappointment of the SNJO set was the house mix. Every instrument had its own mic, so the PA man had plenty to work with. But he chose a hard, shrill approach that turned every big ensemble blast into an unidifferentiated screech.

Trombones were virtually inaudible. The bottom of the band—baritone saxophone and bass trombone doubling tuba—might as well have been playing across the street. The whole point of the big jazz ensemble is balance, a top-to-bottom spaciousness of sound. And the Queen Elizabeth Hall has lovely acoustics on its own, as I can attest from hearing two concerts there last year. What this set needed was careful reinforcement, not audio assault. And it certainly didn’t need the band’s high end in frequent battle with Scofield’s guitar. Grumble, grumble.

But on to the bliss of the first half, and I don’t use the word “bliss” lightly. In every respect, Scofield, Swallow and Stewart are one of the most cohesive units in jazz, and their hour together was superb.

We heard John’s love for Jim Hall in his own contrafact of Charlie Parker’s “Confirmation” (forgive me, John, I forget the tune title) and gorgeous interpretations of “These Foolish Things” and “Someone to Watch over Me.” His cadenzas had great suspense and some clever feints at fingerpicking.

Throughout the set, Sco took a lot of pleasure in those Chet Atkins intervals he uses so cagily, but he really surprised me when he moved into true C&W territory with George Jones’s tune “Girl I Used to Know.” He even recited some of the lyrics before playing it, much as Dexter Gordon used to do when introducing tunes from the great American songbook. John’s take on the tune was deeply emotional without ever becoming sentimental.

The trio does the harder stuff flawlessly as well. Extended versions of “Chicken Dawg” and “The Low Road” had some brilliant Stewart drumming over Scofield’s catchy vamps.

Let me wax about Steve Swallow. Just being in his presence is an honor. Contemporary listeners may need to be reminded that this guy is the Coleman Hawkins of bass guitar. Others preceded him—Monk Montgomery, Carol Kaye, etc.—but he is the man who had the core realization about his instrument and set it on the right path in jazz. Jaco Pastorius and Marcus Miller represent technical wizardry, to be sure, but the primary insight —that the instrument can provide countermelody in the bass clef—is Steve Swallow’s. And no one plays the axe more elegantly or sensitively than Swallow. He watched Scofield’s fingerings intently, adjusting his harmonies to complement and enrich. He bubbled along marvelously at fast tempos and soloed with great taste and style.

Finally, I hail my old friend John. I cannot be objective, since his work is part of the fabric of my life. But one facet of his playing last night struck me with particular force: he has perfected the ability to place notes within a phrase for maximum effect. Every note seems carefully thought out, lovingly placed in space. His work has reached the point where he can do anything he wants on his instrument, and it seems to me that he’s made good progress on the hardest journey of all for an artist—finding ways to express the profound.

Does that sound like too much ambition for a guitar hero? Not if he has the right trio.

Tagged: Alyn Cosker, Bill Stewart, John Scofield, London Jazz Festival, Scottish National Jazz Orchestra., Steve Elman