Music Interview: Blumenthal on the Making of a Saxophone Colossus, Part Two

My conversation with jazz critic Bob Blumenthal circled around two poles. Part one focused on the music of Sonny Rollins. Part two concentrates on the making of the new book, Saxophone Colossus: a Portrait of Sonny Rollins. Text by Bob Blumenthal. Photography by John Abbott. Abrams, 160 pages, $35.

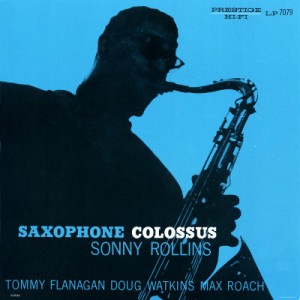

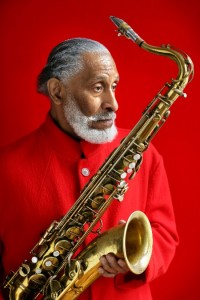

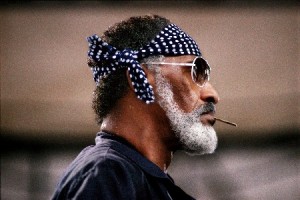

Aside from the Saxophone Colossus album cover, photos of Sonny Rollins are by John Abbott.

AF: It’s almost universally acknowledged that Sonny and Ornette [Coleman] are the two pre-eminent living jazz musicians. How does it feel to write about somebody who is a living icon?

Bob Blumenthal: Well, there’s the icon, and there’s the music. I always try to write about why someone’s output has put them in the place where they deserve to be considered iconic.

Sonny Rollins is a very charismatic individual. He’s got a fascinating life story. He has a real sense of style. He physically fit[s] the “colossus” image. But ultimately there is the music.

The other thing is—and this is something that I really realized a while ago, I guess as I began to write for The Boston Globe—that so many jazz writers preach to the choir. And once I started writing in a daily newspaper, I realized that the challenge became how to simultaneously inform people who know nothing about a subject and bring new insights to people who think they know it as well as you do.

So this became the challenge—how to write about Sonny Rollins so that someone who has never heard him can use this book as a way to acclimate themselves, while simultaneously allowing people who have known his music as well and as deeply as I have to read it and say, “Oh! It all makes sense this way.”

If I did my job, people will understand why he’s an icon without me shouting it from the rooftop in those terms.

AF: Did you ever think when you were writing that this is going to be the definitive book—possibly the last major book until after his death?

Blumenthal: I had learned in talking to editors and agents that people in the publishing industry craved a Sonny Rollins autobiography. When we presented the proposal to him, we wanted him to know that if he felt that our book would get in the way [of that], we could step back.

What he said at the time was, to paraphrase, “I won’t be able to perform, to play forever. When I can no longer play, I’m going to have all the time in the world and nothing to do. While I can still play, I want to give all my energy and attention to playing, and then I’ll worry about the autobiography later.”

I think one reason he was enthusiastic about the book is because there have not been that many books written about him. Eric Nisenson did one [Open Sky: Sonny Rollins and his World of Improvisation. St. Martins, 2000 (hardback); Da Capo, 2000 (paper)]. Peter Niklas Wilson did one [Sonny Rollins: the Definitive Musical Guide. Berkeley Hills, 2001]. It was [first] published in Europe [as Sonny Rollins: Sein Leben, seine Musik, seine Schallplatten. Oreos, 1991], and it’s basically an album-by-album review, with one page of the album cover in color, and a one-page essay on the album.

But there hasn’t really been something [like our book] about Sonny.

[Note: Amazon also lists Richard Palmer’s Sonny Rollins: The Cutting Edge: Continuum, 2004; David Baker’s The Jazz Style of Sonny Rollins. Alfred, 1983; and George Goodman’s Biography of Sonny Rollins. Holt, 1957.]

AF: But did you feel a weight on your shoulders as you were writing? “I’ve been given this responsibility to make the definitive statement”?

Blumenthal: “Definitive”? I don’t know. We know certain historic figures because someone painted a great portrait. And while we hope that we did a job that would allow this to serve that purpose should the sky fall in tomorrow, we think there may be more portraits to come, perhaps a self-portrait.

AF: John [Abbott] gets top billing.

Blumenthal: Well, he originally had the idea to do a coffee-table book on Sonny Rollins. Secondly, Abrams being an art-and-photography house, the photography became a little more of the focus. And finally, when we kicked it around—it’s been a fifty-fifty project—I said, “John, look, if we put your name first, it’ll be the first book on the shelf in all the bookstores, so maybe we should do it that way.”

AF: How long has the project been in gestation?

Blumenthal: About three years.

John is a commercial photographer—you probably know his work from Jazz Times covers and album covers—and he wanted to do a book that would show his more creative side. He originally contacted me in 2007 to write an introduction for a book of photographs of Sonny Rollins.

I told him I would be more than happy to do that, but that it might be worth his while to think about other ways to present the photographs. As I put it, “People who are fans of Sonny and his music generally can’t afford coffee-table books, and people who can afford coffee-table books generally don’t care that much about music generally or Sonny Rollins specifically.”

AF: How did you come up with the five-part structure of the book?

Blumenthal: We spent months trying to come up with a way to make my part and John’s part work [together]. We started quite removed from music, thinking about Sonny and his rigorous discipline as an artist, his spiritual side, his concern for political and environmental issues. Could we find a structure there? And we weren’t getting very far.

It got to the point that we were really getting exasperated. One Friday in a phone call with John, I said, “OK, look John, by Monday we’re going to have a concept. We’re going to take the weekend and figure this out. I’m going to pull out all my Sonny Rollins albums and stare at them in the hopes that something will come to me.”

For some reason, the Saxophone Colossus album really stopped me in my tracks, and I thought, “Well . . . It’s got five tracks—five chapters. It’s a logical title for the book, because it’s his best-known, and one of his greatest, albums.

For some reason, the Saxophone Colossus album really stopped me in my tracks, and I thought, “Well . . . It’s got five tracks—five chapters. It’s a logical title for the book, because it’s his best-known, and one of his greatest, albums.

“What if I use the structure of the album as a structure for writing about Sonny Rollins?

“The ‘St. Thomas’ chapter, for instance, could be a chapter about his rhythmic approach, his affinity for Caribbean music, his relationship with drummers in general and Max Roach in particular. Hmm. Hey, that could be a chapter!

“What would the next chapter be? Oh, it’s the ballad performance [“You Don’t Know What Love Is”]. Well, I [could] talk about his sound, his emotion, his idolization of Coleman Hawkins.”

As I worked through the five tracks, jotting down what I would say in each, I thought to myself that I actually could say just about everything I’d like to say about Sonny Rollins using this structure.

We went to see Sonny in September of 2008. He had already said OK—he was comfortable with John and me doing a book about him. But now we had a specific approach. He looked at the proposal, and he said, “Brilliant! This is brilliant! What a great way to do it.”

So then the next question became one of “What’s the best way for us to collaborate on this?” And I keep going back to this comment [drummer] Elvin Jones made to me when I asked him what kind of direction [saxophonist John] Coltrane would give his band when he’d bring new material in to record it. And, to paraphrase, Elvin said, “Look, I didn’t tell John how to play the saxophone, and he didn’t tell me how to play the drums.”

So I mentioned this to John [Abbott], and I said, “I think this is the way we have to work. You’re the photographer. I’m the writer. I don’t think that a rigorous step-by-step match of prose and photograph works. When I finish a chapter, I will send it to you, and you see if that leads you to select certain photographs or to decide what to include and what to leave out.”

AF: The concept is built on an album recorded in 1956, and the photographs all begin in 1980. So there are no “historic” photographs of Sonny in the book except second-hand, via album covers he’s holding or posters on the walls. Did you grapple with that issue and say, “We need some vintage photographs to provide the full perspective”?

Blumenthal: We don’t simply talk about this album and these tracks. Sonny is not someone who made an iconic recording 55 years ago and then has just coasted on that. We use it as a starting point—[for example, in] the “Moritat” chapter, [we talk about] his unusual song choices, going to the present time, when he’s playing Schubert’s “Serenade,” “Sweet Leilani,” [and other unexpected repertoire]; [in] the “Strode Rode” chapter, we talk about [his compositional approach, including] some other interesting music he’s written over time.

I kept saying to John, “Be prepared for the complaints: ‘Where’s the picture of Sonny with a Mohawk?’[circa 1964]” But John wasn’t taking pictures then.

AF: Anyone who writes about music is essentially trying to translate an ephemeral form into something concrete. How have you grappled with that issue through your career, and how does this book fit into that struggle?

Blumenthal: It’s another challenge in an ongoing dilemma.

I think that music could be the most difficult subject of all [to write about], in part because all of us are so reliant on visual stimulation. Whenever I do a [public] presentation, I always say, “There will be no visual aids. This is about using your ears. I have a list of the music I’m going to play for you, but I’m not going to give it out until I’m done, because I don’t even want you looking at that piece of paper. I just want you listening.”

Having said that, I feel that one way to address that challenge is to grapple with music in a context that people are more comfortable with, such as the written word, such as visual images. And until we all learn how to communicate musically among ourselves, I think it’s probably the best that we can hope for. You just try to be honest in what you hear, to apply standards that you develop over time.

Beyond the music, there’s the respect that John and I have for him as an individual. And his example. Those aspects of Sonny Rollins are not notated on score paper.

AF: What else would you like potential readers to know?

Blumenthal: I think I speak for John in saying that we both recognize that we had to create something unique. The idea was not to do “The Making of Saxophone Colossus.” It wasn’t a book of photographs with an introductory essay. It wasn’t a book about Sonny Rollins with pictures. The essays aren’t intended to be “comprehensive,” just as the photos are not a comprehensive document of his entire life. Maybe we’re giving ourselves too much credit, but I think we’ve created something unique, and we both feel very good about that until people tell us otherwise.

AF: You spend all this time working on the book, and the manuscript, and the editing, and then you see it in the store finally, and then, your eyes go around and look at all the other books. And you think, “My God, there are thousands of choices! How will people ever come to my book?”

AF: You spend all this time working on the book, and the manuscript, and the editing, and then you see it in the store finally, and then, your eyes go around and look at all the other books. And you think, “My God, there are thousands of choices! How will people ever come to my book?”

Blumenthal: That’s where a publisher really means a lot, I think. So far, the experience with Abrams has been great. We couldn’t have asked for a better publisher for this kind of book.

I think the challenge is one confronted by any author of any book now. I’m still taken aback when people say to me, “Oh, we really like your first book, because you don’t have to read it through from beginning to end.” I hear this from friends of mine who are professors.

I say, “If you can’t sit there and read through an entire book, who in the world is going to read an entire book now?” But the short attention span is now the rule and not the exception. As time passes, it becomes clearer and clearer that that’s the reality.

Let me throw it back at you [in regard to your book]: did you get this, “Oh, I’d love to read it, but I just don’t have the time to sit down and read a book”?

AF: The people who took the time to read the book [Burning Up the Air: Jerry Williams, Talk Radio, and the Life in Between, co-authored with Alan Tolz. Commonwealth Editions, 2008] said, “Wow! What a lot of work! This was terrific. I couldn’t put it down.” On the other hand, there were many people to whom I gave the book who did not read it, and they never commented at all. Which is fine. I’ve gotten accustomed to saying, “Everybody who’s actually read the book has really liked it.”

For me, it was a labor of love. I felt constantly lucky through the whole process, [to find Alan Tolz, who was such a simpatico collaborator, and] that I’d found an agent and a publisher and gotten the opportunity to do it, and so, when it was finished and we’d done all the promotion we could and it didn’t move to The New York Times best-seller list, I thought, “Well, I’m still proud of it.”

Blumenthal: That’s kind of my feeling about this. I mean, I thought originally, “Oh, it’s going to come out on his 80th birthday, and it’ll come out right before the fall influx, and it should get a lot of attention, and it’s going to look great, and he’s an iconic figure anyway,” and on and on.

But ultimately, it’s a book about a jazz musician.

But to go back to Sonny as a role model and somebody who influenced me and influenced John, he said something when I interviewed him in Vermont back in June. I asked him if he could explain to the audience how at a time [in 1959] when everybody was saying, “You’re the new genius of jazz, you are the future of the music,” he could basically drop out because in his own mind he wasn’t as good as people said he was.

And he said, “Never believe what people say when you know otherwise.”

Tagged: Abrams, Bob Blumenthal, Jazz, Saxophone Colossus, Sonny-Rollins

Excellent interview. I’m going to pass it on. Thank you.