Film Review: “WHITEY” — Rat or Robin Hood? Whitey in his Own Words

By the end of the documentary, you’re in no doubt that Whitey Bulger was beneath dignity. Though not in his own eyes. There’s even vanity left in a crook who trims his white beard so scrupulously.

WHITEY: The United States of American vs. James J. Bulger, directed by Joe Berlinger, 130 minutes (At the Sundance Film Festival). As part of the Sundance Film Festival USA. The film will screen at the Coolidge Corner Theatre in Brookline, MA, opens on June 27.

By David D’Arcy

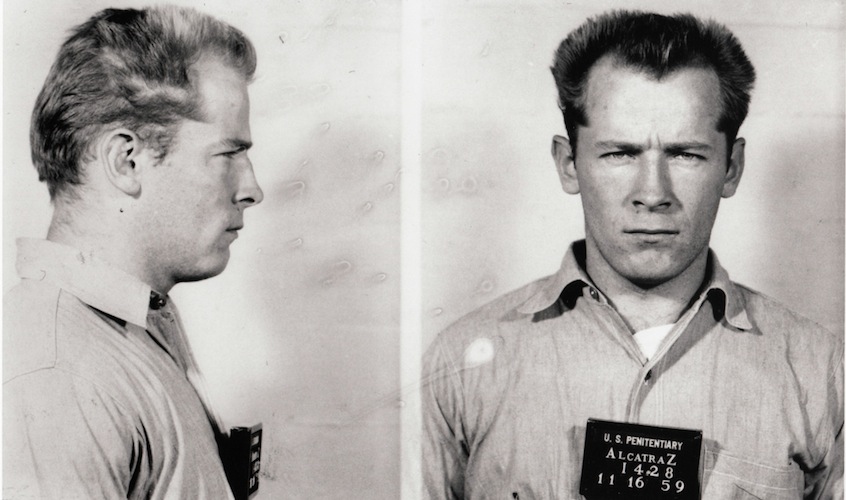

WHITEY: The United States of America vs. James J. Bulger revisits the pursuit, prosecution and defense of William Bulger, the crime boss of the Boston mob, who is now serving two life sentences, plus five years. It makes you feel glad that he’s inside, even if you’re paying all his expenses.

It is also a reminder of unanswered questions that remain after Bulger’s conviction on racketeering charges that implicated him in a lot more than the 11 murders for which he was found guilty, along with extortion, money laundering and drug trafficking.

Even Bulger’s lawyers acknowledge that their client was a criminal, but they still dispute the charge that he was an FBI informant. The long documentary by Joe Berlinger explores that contention from the perspective of the Bulger camp, scrutinizing Whitey’s contacts with law enforcement figures, one of whom, childhood Southie friend and former FBI special agent John “Zip” Connolly, is serving a long sentence in federal prison. The documentary asks whether Bulger was a turncoat against other criminals in his own community – a betrayal of the mythic honor among thieves – or whether he was a successful crime entrepreneur whose cost of doing business involved bribing officials all over government.

Bulger’s lawyers argue the latter. The evidence shows that Bulger’s assistance to the FBI in fighting the Italian mob made business sense for him, increasing his gang’s market share in Boston.

Was he a rat or was he a Robin Hood? In Berlinger’s laboriously detailed doc, we hear from plenty of Bulger’s victims and their relatives. Plenty is an understatement, and these victims are known to anyone who followed the chase and punishment of Bulger in the daily media and the many books on the man. We get a flood of grief from angry relatives as Berlinger’s team accompanies them in their cars all over town. The ride-long camera is a leitmotif in WHITEY.

The anger is no surprise, given that Bulger’s victims were killed in savage ways – even by mob standards – and were subjected to mutilations intended to conceal their identities. Think of young women who had all their teeth pulled and their limbs severed because they knew too much, and you get a sense of the venom that comes out in tears and curses from loved ones on the screen.

We see the pretty face of Debra Davis, a former Bulger girlfriend who knew too much. We don’t see the gruesome dismemberment in Berlinger’s doc. Bulger was what you might call an old-fashioned murderer. He didn’t film his killings and send them out on the internet. He knew that photographs of the carnage were a liability. And there wasn’t much in the human remains that the newspapers would dare run in a picture. Yet the disappearances were known, and Bulger lived nicely off his reputation, which kept all levels of cops coming by with their hands out and kept local businesses and other mobsters in fear of him.

Killing women, we’re told, was beneath the dignity of the good bad guy that Whitey wanted his official persona to be. So was the terrorizing of one’s own neighborhood. By the end of Berlinger’s doc, you’re in no doubt that Whitey Bulger was beneath dignity.

Not in his own eyes. There’s even vanity in the crook who trims his white beard so scrupulously.

And in WHITEY, we hear something unprecedented, Bulger’s own voice. The gangster talks over the telephone to his lawyer, J. P. Carney. It’s a tremendous scoop for the documentary (courtesy of that lawyer). The message is that something set Whitey straight on his road to Damascus – or to Santa Monica, where he was caught. That something, he said, was his companion, Catherine Greig. Yet the murderer’s argument that his girlfriend on the lam changed him into a better man is hollow: it is about as persuasive as what we might hear from OJ Simpson. Less persuasive, as it happens. Bulger didn’t testify, and he didn’t walk. The mounting testimony of his crimes leaves you thinking of that memorable line from the jury in The Producers: “We find the defendants incredibly guilty.”

Guilty or not, part of what Bulger and his lawyers were trying to say rings true. If Bulger was an FBI informant for 30 years, it’s reasonable that more than a few people knew what he was doing. Why haven’t more them been prosecuted?

Wait a minute – Bulger and his team stated unambiguously that the killer wasn’t an FBI informant, but let’s grant that every defendant is entitled to his own contradictions and convolutions.

In court, Bulger and his lawyers argued that the US attorney in Boston, Jeremiah Sullivan, promised Bulger immunity from prosecution in exchange for information – in effect, a license to kill. Naturally, the US attorneys who prosecuted the case for the federal government dispute this, but Sullivan, who allegedly issued the immunity, is dead.

How convenient. No one else besides Whitey Bulger and his lawyers seem to know about that deal. Their only forum now is this film.

Does Berlinger’s documentary come at the end of Bulger’s 15 minutes? It takes someone who’s deeply interested in the Bulger case to see the film as more than a recycling of existing information. I’ll admit that I’m one of those Bulger junkies.

Yet even for me, Berlinger’s film can still be slow-moving and repetitive, with more helicopter shots than you can count, most of them veering above the Federal Courthouse in Boston. Are we meant to conclude that the eyes of the world were focused on the courtroom, where Berlinger was not permitted to film? One opening shot from the sky would have been enough.

Those superfluous shots will be out of the film once Berlinger cuts WHITEY down to the 88 minutes that CNN, his funder and distributor, requires for broadcast. The documentary will still be missing some crucial testimony. We don’t hear from William Bulger, the brother and former Massachusetts Senate president whose omerta about Whitey on the lam delayed the fugitive’s capture. And we don’t hear much from the FBI, except for Robert Fitzpatrick, an honest FBI agent with roots in Southie who was forced to retire after he dared to question the bureau’s special relationship with Whitey. And what about those seven paintings from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum which still haven’t turned up? Somehow I think Bulger and his associates and a few friends in law enforcement may know more than they’re telling.

WHITEY suggests that the man whom the FBI has the most reason to fear is still Bulger himself. Why shouldn’t he spill the beans on everyone whom he bribed or paid off? What more does he have to lose, except his relative comfort in prison? As the camera follows the fortified motorcade that takes the jailed Bulger to and from the courthouse, the clear implication is not that Bulger might find a way to escape, but that someone might find a way to eliminate him.

Has a page turned in Boston crime? Yes and no. Berlinger’s film opens with Stephen “Stippo” Rakes recallng how Bulger barged into his liquor store and took the place over. His strategy was to tell Rakes that his daughter might grow up without a father. By the end of the documentary, Rakes is dead, poisoned via cyanide in his iced coffee. Rakes was preparing to testify against Bulger, but the killer wasn’t Whitey this time. It was another crook with a record, William Camuti, who had a business deal with Rakes that went sour. It sounds like Bulger’s way of settling an argument, but Bulger probably wouldn’t have approved of the method. It left too many clues, and Rakes’s body was left intact.

David D’Arcy, who lives in New York, is a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He reviews films for Screen International. His film blog, Outtakes, is at artinfo.com. He writes about art for many publications, including The Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary, Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.