Book Review: “Wail” — A Great Biography of Jazz Legend Bud Powell

Peter Pullman deplores (without bathos) the wreckage of Bud Powell’s life and mourns (without tears) the consequent loss of so much masterful music. And his story of Powell’s life is even grimmer than the one we have previously been told.

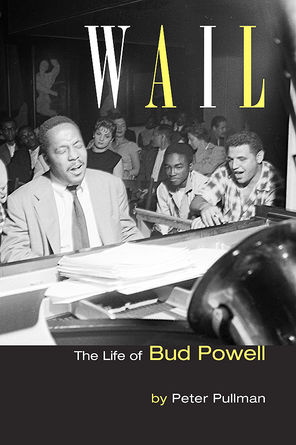

Wail: The Life of Bud Powell, by Peter Pullman. Bop Changes, 476 pp. $20.

By Steve Elman

For the foreseeable future, Miles Davis and Charlie Parker are secure as jazz gods. Dizzy Gillespie has a comfortable place in the pantheon as well. Thelonious Monk is just Monk, beyond any category and possibly better-known to the general public now than even Duke Ellington is. Near these four bebop pyramids, there used to be Bud, the Sphinx, as great an artist as any of the others, but unapproachable, even inexplicable, as a human being. Now the sands have begun to rise around Powell, and even his mystery is no longer the mythic tragedy it used to be.

At one time, Peter Pullman’s Wail would have been embraced by a major publisher and been given the editorial care, professional design, and portfolio of photos that it deserves. It would have taken its place on bookshelves alongside the great biographies of Armstrong, Ellington, Mingus, Monk, and many other figures much less important to American music. Instead, because things ain’t what they used to be for books and jazz legends alike, Pullman decided to issue this landmark work as an e-book in February 2012, and he self-published the first print edition a year ago. Since then, it has been largely ignored by the jazz press and the mainstream press alike.

This is deeply unfair to the author and to his subject. Pullman has striven to give us an uninflected portrait of Bud Powell, and Wail is admirably free of the overwriting and handwringing that so often has accompanied discussion of Powell’s work. Pullman is patient and persistent, letting every fact add another tessera to the mosaic. As I read it, I felt how arduous it was for him to make sense of the tangles of Powell’s behavior and to do justice to a great artist trapped inside a deeply flawed, even tortured personality. Time will tell whether his reward will be commensurate with almost twenty years of interviewing and research that he put into the project.

Howard Mandel should be credited as one of the first to read and review the book, on the website of the Jazz Journalists’ Association in August 2012 and Pullman subsequently reissued that review on his own website, where it piqued my curiosity. I was particularly struck by Mandel’s speculation about whether the mental and emotional problems Pullman describes might have been a form of autism. (There’s plenty of evidence to support that diagnosis in Wail, although Pullman never strays into fantasies about how Powell might have been viewed by today’s mental health professionals.)

Simply put, in no other jazz master’s life does mental disability play so important a role. Even Thelonious Monk, who is convincingly described as bipolar in Robin D. G. Kelley’s Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original (Free Press, 2009) and who was crippled by his mental problems in his later years, had much greater control over his life and career than Powell did.

Pullman does not make Powell the hero of his own life or a tragic figure battered by fate. He does not try to read Powell’s mind or guess at his feelings. But he is nonetheless profoundly sympathetic. He deplores (without bathos) the wreckage of Powell’s life and mourns (without tears) the consequent loss of so much masterful music.

The conventional Powell narrative is simple – he was a tragic genius, initially brilliant as a composer-improviser and awe-inspiring as a piano virtuoso, who was soon felled by unsympathetic psychological treatment, drugs, and alcohol, leaving him a pathetic shell, dead about two months shy of his 42nd birthday. There is much more. If anything, the story is even grimmer than the one we have previously been told.

Powell’s estrangement from the outer world defies any simple characterization. Various aspects of his antisocial behavior might be linked to some form of autism, and/or: the bewilderment of an idiot savant; the immaturity of a prodigy who never grew out of his need for external reinforcement; the frustration of an inarticulate artist, imprisoned by his inability to express himself effectively outside of his art; the anger of an unappreciated genius; the fog and obsessiveness of a chronic substance abuser; the antics of a bebop trickster; the fear and fury of a sensitive African-American man who was unable to inure himself to the overt racism of his society; and, most familiarly to those who have read even a smattering of Powell biography, the damage inflicted by crude electroconvulsive therapy upon an unsuspecting patient.

On this last point, Pullman succeeded in doing something no one else has, and his effort serves to illustrate his dedication: he sought access to the records of Powell’s hospitalizations at Creedmoor State Hospital in Queens and Pilgrim State Hospital in Brentwood (on Long Island), finally winning victory in New York State’s Supreme Court. After decades, a jazz journalist was able to rely on primary-source information instead of second- and third-hand accounts to illuminate one of the darkest corners in a great artist’s life. In sober detail, Pullman gives us the facts about some thirty applications of electro-convulsive therapy that Powell endured at Creedmoor in 1948, and another thirty-three at the same facility in 1952. He doesn’t need to resort to overwrought prose to make the reader writhe:

[In January 1948,] without any provocation that the psychiatrists noted, they reported that Powell erupted. He was ‘out of contact, assaultive, and markedly resistive’. It was reported that he had to be restrained by straitjacket . . . His first course of ECT began on February 4 and lasted until April 5, during which time twenty-one grand mal reactions were obtained . . . Powell’s condition after this series of treatments: ‘unimproved.’

Unlike the safety measures that hospitals use with ECT today, Powell . . . wasn’t given effective restraints – so, when his body convulsed, he might have suffered additional trauma, even a sprain or broken bone (which wouldn’t have shown up on any report). With no standardization in ECT equipment, the voltage and amperage measurements varied from one machine to another. Powell wasn’t given anesthesia before the procedure. And the electric current was applied using two electrodes, one attached to each of his frontal lobes (when the therapy is administered today an electrode is attached to one lobe). He probably suffered skin abrasions and hair-singeing as well.

But Pullman sought even more detail about the treatments, tracking down the last surviving psychiatrist from Powell’s time at Creedmoor, and in a footnote, he quotes the doctor’s unwittingly revealing rebuff to his research: “What happened to him at Creedmoor, in the state hospital, had nothing to do with him as a creative person, an artist. And that’s what you’re dealing with. Goodbye.” [Pullman’s italics]

Pullman unflinchingly relates a depressing catalog of Powell’s self-absorptions, slights and cruelties: staring fixedly and unnervingly at people in his audience during other players’ solos; invading a nightclub and pushing the playing pianist off the bench so that he could take over; taking a drink out of another man’s hands at a bar and getting into a fight over it; insulting people in the audience who didn’t applaud; pouring beer over Fats Navarro during one of the great trumpeter’s solos; abandoning gigs in mid-performance; slapping and mocking Charlie Parker; rushing through rehearsals of complicated originals and then reviling his fellow musicians for failing to play them properly; apologizing to the audience for what he perceived as second-rate playing by his accompanists; taunting Max Roach at the recording session that produced their joint masterpiece, “Un Poco Loco.”

Case in point: Powell’s loathing for George Shearing, the blind pianist who imitated his style but never could match his creativity: “Powell liked to approach Shearing quietly, knock on his forehead as if it were the door to his house and say, ‘George! It’s me, Bud.’”

Bud Powell biographer Peter Pullman — his book is honest, penetrating, and a profoundly important contribution to artistic scholarship.

Pullman makes it clear that Powell was both the victim of his demons and a collaborator with them. As a result of the research and intelligence on display in Wail, it will only be possible for future writers to describe Powell as a tragic figure out of willful ignorance or naiveté. Again, Pullman’s words: “. . . he had no other interests [that is, other than music and intoxicants] and no hobbies; he didn’t care to know anything that was in the news. And though he frequently had amorous feelings for women, he wasn’t capable of maintaining his end of a conversation let alone of a monogamous relationship.”

Along the way, he provides sketches of the people who tried to help or manage Powell – his mother, Pearl; saxophonist Jackie McLean; manager Oscar Goodstein; attorney Maxwell Cohen; French jazz fan Francis Paudras; and his companion (never his wife), Altevia “Buttercup” Edwards – people motivated alternately by love for him or by the chance to exploit him. Pullman shows, devastatingly, how each was eventually exhausted by this “brittle, searing talent [who] desperately needed acceptance.”

Pullman’s attention to detail extends even to the atmosphere and decorations of the venues where Powell played. As a result, he brings the reader into these historic clubs in a way that very few other jazz writers have. His description of the owners, managers, décor, personalities and performance practices at Birdland (including a scathing sketch of Pee Wee Marquette, its midget MC), is nothing short of brilliant. It puts the reader knowledgeably into the club and at the same time provides him or her with the background he or she needs to understand its operations (and the operations of the shady characters that created it).

Another example of Pullman’s thoroughness: as an addendum to the book – almost as if he simply couldn’t help himself from doing so – he provides a short history of the cabaret-card system in New York City. Apart from its value as an illustration of the milieu in which Powell had to work, it is required reading for anyone who has ever heard of the system and how the police department used it to keep some artists from earning a living in the most important jazz city in the world. This blunt instrument came down on Powell, Monk, Parker, Billie Holiday and Lenny Bruce, among many others.

I don’t mean to imply that Pullman gives short shrift to Powell’s art. Wail sends us back to the music, as any good musical biography should. Pullman gives ample space to Powell’s technique, his innovative composing, the gigs that he can document, and the recordings. He goes to great lengths to describe the circumstances of the recording sessions as well as the music produced in them.

Bud Powell — nearly every one of his compositions is eminently singable or whistle-able, if you can sing or whistle rapidly enough.

Powell’s musical highs and lows were extreme, and Pullman debunks the conventional wisdom that he had a few years of genius and then a long pathetic decline. In truth, Powell’s overall output was even more erratic than is usually thought. Pullman shows that he was inconsistent from the very beginning, and conversely, capable of greatness for almost eighteen years of his performing career. In his survey of Powell’s recordings, Pullman finds only twenty or so that are unequivocally great, most of them from the early years. However, Pullman points to “John’s Abbey” and “Cleopatra’s Dream” (from 1958) as top-level performances in a period when Powell was supposedly well past his prime. Pullman shows that the decline became irreversibly terminal only in Powell’s last two years (1962 – 1964), when he returned from France to New York.

When he deals with individual performances, whether great or painfully bad, Pullman restricts his analyses to broad strokes. For serious musicology, you’ll have to consult other sources, since a work of this scope simply cannot do justice to so much deeply sophisticated music. But Pullman’s remarks are consistently well-chosen; I went back to “John’s Abbey” and “Cleopatra’s Dream,” recordings I haven’t heard in more than twenty years, and found that Pullman’s perceptions were fully justified by the music. I also investigated other tunes from those sessions (found in The Complete Bud Powell on Verve, by the way) and came to realize something I’d forgotten: that Powell put so much art into each performance that each demands to be savored and enjoyed apart, rather than as part of a set or an “album.” Powell came from a time when the three-minute 78 single was the norm of the recording industry, and his thinking was conditioned by those limitations. I also was reminded of how tuneful his writing was; nearly every one of his compositions is eminently singable or whistle-able, if you can sing or whistle rapidly enough.

In a few cases, where the music justifies it, Pullman goes deeper. His analysis of “Un Poco Loco” shows how well he understands Powell musically and how well he hears the tense mutual interplay between Powell and the drummer, Max Roach. He sets the scene for the session well, giving insight into Powell’s desperate state of mind, and his sudden disappearance at the time the session was to begin (probably to score heroin or to stoke an alcoholic buzz). He properly notes the disconnect between these personal factors and Powell’s all-business approach to the music at hand, diligently working out his “Poco Loco” solo over the course of three takes. He makes the sweeping and absolutely correct assertion that “Nothing in jazz had been so successfully wedded to what the latin-jazz modernists were doing.”

However, this analysis also demonstrates the limitations Pullman has imposed on himself and the difficulties of adequately assessing Powell’s innovations. “Un Poco Loco” has been the subject of intensive analysis, and it offers opportunities for even broader generalizations. I am hardly a musicologist, but if I were advising Pullman, I’d say that he also could have identified Powell’s improvisation here as the first modal solo in jazz, exemplifying the approach to harmony codified by George Russell (certainly one of the “latin-jazz modernists” Pullman refers to) in his Lydian Chromatic Concept and prefiguring the experiments of John Coltrane and others fifteen years later.

But that’s to be expected. When a work is as ambitious and comprehensive as Wail, it will inevitably fall short of expectations in one way or another. Here are several more concerns:

First, no discography. Pullman probably decided early on that a project of this magnitude would preclude a comprehensive list of recordings, and he certainly knew that a very good (though now seriously dated) Powell discography had been created by Alyn Shipton and published in Shipton’s 1993 biography, The Glass Enclosure (Bayou Press, 1993), co-written with Alan Groves. Still, you’ll come away from Wail wishing that you had a list of recordings to consult, and for that, I recommend the information compiled by the Jazz Discography Project. But even this source is not updated with CD reissues and compilations.

Second, as a fellow obsessive, I’m both bemused and irked by some idiosyncrasies of Pullman’s writing. They bring the reader up short time after time, and although I understand his logic, I think he strains at gnats in these cases:

In his author’s note, he explains his rationale for creating the terms “afram” and “euram” as contractions of “African-American” and “European-American” and as substitutes for the inaccurate (and “invidious,” as he points out) shorthand of “black” and “white.” Since “afram” and “euram” are used sparingly in the book text, I can’t understand why he didn’t simply use “African-American” and “European-American” as they are.

He also chooses to omit the common use of “the” before the names of concert venues. In writing about Boston’s venues, for example, Pullman would write “Regattabar” and “Beehive,” rather than “the Regattabar” and “the Beehive,” even when the venues themselves use the article. And he has a valid point; we don’t write “the Symphony Hall” or “the Scullers,” and if we were writing about “New York City’s Village Vanguard” we would omit the article, even if we wrote “the Village Vanguard” in the next sentence. This inconsistency is the result of our sloppy thinking and casual speaking, but it is such a common usage that adhering to this particular rule seems a little pedantic.

Third, as in any self-published work, there are regrettable text flaws. Every author needs a sympathetic editor, and Pullman’s work would have been marginally improved if an editor had had the chance to correct moments of clumsy expression that sound like they were dictated into speech-recognition software (example: “But the professional competition that he was facing now, in midtown, he was probably not prepared for.”).

These concerns should not discourage anyone interested in Powell’s work, jazz life, and human drama from sampling Pullman’s book and ordering it if they are intrigued. (There’s a generous free helping on his website.) Wail is the book Bud Powell has always deserved. It is honest, penetrating, and a profoundly important contribution to artistic scholarship. One could even describe it as noble.

Steve Elman’s forty-three years in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and currently, on-call status as fill-in classical host on WCRB / Classical New England three years. He was jazz and popular music editor of the Schwann Record and Tape Guides from 1973 to 1978 and wrote free-lance music and travel pieces for The Boston Globe and The Boston Phoenix from 1988 through 1991.

He is the co-author of Burning Up the Air (Commonwealth Editions, 2008), which chronicles the first fifty years of talk radio through the life of talk-show pioneer Jerry Williams. He is a former member of the board of directors of the Massachusetts Broadcasters Hall of Fame.