Book Review: “The Cool School” — What Does it Mean to be Hip?

In a way, this collection of hip writing, a “literary mixtape,” is the ultimate embodiment of the vision of the Hipster-as-Curator.

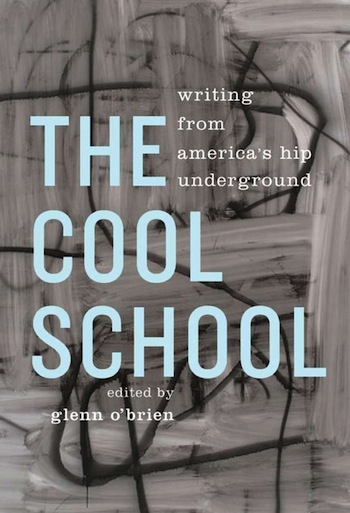

The Cool School: Writing from America’s Hip Underground, edited by Glenn O’Brien, The Library of America, $27.95, 484 pages.

By Troy Pozirekides

The appellation “hipster,” initially intended for the jive-talking jazz hounds of the late 1940s, has had its meaning blurred and usage expanded in modern parlance. In The Cool School: Writing from America’s Hip Underground, Glenn O’Brien (GQ’s “Style Guy” and author of How to Be a Man) has brought together fifty-seven pieces of writing from the “original hipsters” in a collection that charts the course of the cool consciousness through the tumult of the twentieth century. These writers—from jazz musicians to Beat poets to avant-garde filmmakers—are united in their detachment from the mainstream, from all that is terminally unhip. These notes from the underground collect the common experience of “hip” artists across several generations, who reject prevailing social mores in favor of willful self-exile.

The words “hip” and “hipster” (along with variants “hep” and “hepcat”) came into being as part of the lingo of jazz artists. As O’Brien writes, “the essence of hipsterism is argot,” and the writings of these musicians—Mezz Mezzorow, Miles Davis, Babs Gonzalez, and others—capture the innovation of a new underground music, bebop, told expressively in varying degrees of jive talk. The iconic figure of this movement was Charlie “Bird” Parker, whose musical innovations as well as downtrodden look and lifestyle helped to make him into the first role model of many a would-be hipster. Miles Davis recalls:

[Bird] was cool, with that hipness he could have about him even when he was drunk or fucked up. Plus he had that confidence that all people have when they know their shit is bad…And, man, I was amazed at how Bird changed the minute he put his horn in his mouth. Shit, he went from looking real down and out to having all this power and beauty just bursting out of him. (Excerpt from Miles: The Autobiography)

Musicians like Davis weren’t the only ones who took note of the aura of hipness around Parker. A group of writers who would eventually be labeled “Beat” sought to emulate Bird’s artistic energies and spark a literary movement with a language all their own. Jack Kerouac would even write the last few choruses of his poem “Mexico City Blues” as a sort of intercessional prayer directed at Bird. He is featured in The Cool School, but fellow Beat pillar Allen Ginsberg is noticeably absent. His poem HOWL is referenced by Diane DiPrima as ushering in “a new era” but is not itself included or even excerpted. Still, the other writers of this generation, DiPrima, LeRoi Jones (now Amiri Baraka), Neal Cassady, Gregory Corso, Herbert Huncke, and John Clellon Holmes, evoke the diffusion of the jazz spirit into a lasting literature that embodied their collective otherness. In Diane DiPrima’s words:

Our chief concern was to keep our integrity…and to keep our cool: a hard clean edge and definition in the midst of the terrifying indifference and sentimentality around us—“media mush. (Excerpt from Memoirs of a Beatnik)

Following the Beats, the hipster ethos helped to build the hippie, originally denoted by Del Close as “a junior member of Hip society, who may know the words but hasn’t fully assimilated the proper attitude.” This next wave of writing occupies a varied spectrum: Bob Dylan’s blissful recollection of his early days in New York, the psychedelic fiction of Randolph Wurlitzer, and William Burroughs’s and Brion Gysin’s spirited paeans to Hassan-i Sibbah, the founder of the crusade-era Assassins. Also included are stand-up comedy innovators Mort Sahl and Lenny Bruce, who demonstrate a shift in the hip aspiration from a literary/poetic mindset to a more plainspoken and direct form of truth seeking generated by performance.

Editor Glenn O’Brien — he knows that the rise of the Internet has encouraged a calculated eclecticism.

The writers of the post-hippy era begin to show signs symptomatic of the much-maligned modern hipster. Jack Smith’s zany tribute to camp actress Maria Montez—he loves her while knowing full well she is an atrocious actress—might be the first documented instance of hipster irony, all-too-familiar today. Similarly, Lynne Tilman’s depiction of a group of men putting down Mozart as “a basic talent, without intellect” brings to mind the memorable scene in Woody Allen’s Manhattan, where Diane Keaton and Michael Murphy condemn Gustav Mahler, Lenny Bruce, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Norman Mailer—“all terrific” to an incredulous Woody Allen—to the “Academy of the Overrated.” The ironic appropriation of camp, combined with a contempt for mainstream tastes, have become hallmarks of what O’Brien calls “the new class hipster.”

O’Brien, in his introduction, is cognizant of this shift in the hip sensibility:

I realized that the word had changed meaning while I was dozing in the sun or strolling on a golf course…I had seen the hip career choice change from rock musician or painter, to DJ or curator. Life had become a matter of selecting among ready-mades…

Rather than a pursuit of individual, authentic expression, the focus of the “new class hipster” is the aggressive expression of individual taste—the more underground, unknown, repurposed, the better. The social fabric of the Internet has led to an explosion in such calculated eclecticism. As O’Brien writes, “in the digital age the gatekeepers are out of business.”

In a way, this collection of hip writing, a “literary mixtape,” is the ultimate embodiment of the vision of the Hipster-as-Curator. O’Brien refers to it as “a compendium of orphans” selected by “filtered randomness,” which has a haphazard tone about it that suggests little more thought or planning than what goes into a Pinterest post. Luckily, O’Brien’s book has an advantage over an online pinboard, in that the words of the writers he has selected, rather than their likenesses—no matter how cool that dusky black and white photo of Kerouac fiddling with the radio knob is—have the potential “to whet cool appetites” for more, and as a “guide to future thought crime,” may in the right hands, incite a hip revolution all over again.

Troy Pozirekides is a writer, critic, and editor. Currently a senior at Boston University, he specializes in British and American literature of the twentieth century, from the poetry of Philip Larkin to the works of Jack Kerouac and the Beat Generation. Troy is also a musician and jazz aficionado, playing trumpet and guitar. Follow him on Twitter at @tpozirekides.

Slim Gaillard was the originator . Tee Say Melee!!