Graphic Novel Review: No One Wins — Gene Luen Yang’s “Boxers & Saints”

Although Gene Yang envisions a similarity between the Boxers (once transformed into their mythological hero aspects) and modern superheroes, BOXERS & SAINTS is far from a simple good vs. evil slugfest.

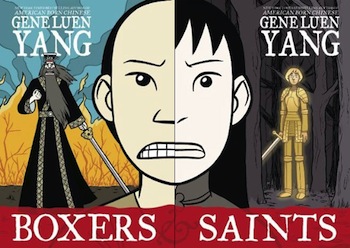

Boxers & Saints, written and illustrated by Gene Luen Yang. Colored by Lark Pien. First Second Books, recommended for High School and Up. Boxers, 328 pages, $18.99. Saints, 170 pages, $15.99.

by Pat Tong

What intrigued me most at first about Boxers & Saints, Gene Luen Yang’s graphic novel about the Chinese Boxer Rebellion, was how the author would deal with the material’s inherent moral dilemma. Where would a Chinese American Catholic’s loyalties lie? Would they be with the people featured in the first volume of the diptych Boxers, downtrodden Chinese peasants fighting against foreign oppressors and intolerant missionaries and priests? Or would they be with the protagonists of the second book, Saints, brave and well-meaning Christian men, women and children (western and Chinese) slaughtered by the violent and bloody uprising?

After decades of humiliating foreign colonial control under the UK, Japan, France, Germany, Italy, Russia, Austria and the US, a nationalist movement comprised largely of Chinese peasants and farmers arose. The oppression of China included the forced import of opium, Christianity, and preferential treatment and legal immunity for foreigners and their business interests. Originally sworn to rid the country of their Qing Dynasty rulers and all foreigners, the Boxers eventually allied with Empress Cixi. It is estimated that the Boxers killed several hundred foreigners and several thousand Chinese Christians during their campaign. The rebellion culminated in the siege of the foreign legation quarters and the Roman Catholic cathedral in the capital city of Beijing.

An international military force was sent to quell the uprising, including several thousand from the US McKinley was possibly the first president to send military troops overseas against a recognized government without first having obtained a declaration of war or Congressional consent. The Qing court fled to Xi’an, leaving the imperial palaces unprotected. The invasion left China worse off than before the uprising: reparations of over three hundred million dollars, foreign garrisons stationed to protect various countries’ interests, and a frenzy of looting, raping, violence, and murder by foreign soldiers, diplomats, missionaries, and journalists. The carnage was so repugnant that it was criticized by such American icons as Mark Twain; the indignation may have tempered the initially positive perception of American military action.

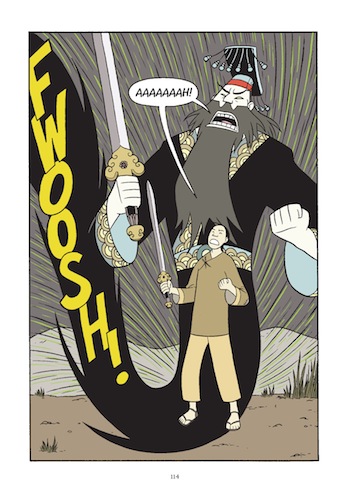

In BOXERS, Little Bao transforms into a mythological hero. Copyright Gene Luen Yang, used by permission of First Second Books.

Yang, deservedly twice-nominated for a National Book Award for Young People’s Literature (once for American Born Chinese in 2006 and now for Boxers & Saints), has written a subtle and complex parallel story inspired by this traumatic historical event. One strand of the narrative presents the viewpoint of Little Bao, an opera-loving farmboy who eventually becomes leader of a rebel group called the Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fist. The other storyline features the perspective of Four Girl/Vibiana, a lonely and misunderstood country girl who converts to Christianity. Through her frequent visions of Joan of Arc — and her own distinctive understanding of life — she strives to discover her larger purpose in the scheme of things, and to create an identity for herself by way of this quest. The stories of Little Bao and Four Girl/Vibiana weave in and out of both books, creating an ultimately tragic tapestry of love, cruelty, humor, and courage.

Although Yang envisions a similarity between the Boxers (once transformed into their mythological hero aspects) and modern superheroes, these books are far from a simple good vs. evil slugfest. Superman only defeats his foes, he never kills them (okay, let’s not get into that terrible movie) and he doesn’t end up in tears afterward. This epic story introduces us to character after character who is unable to decipher the other’s intentions. Yang probes deeply into the hearts of most of these flawed personalities, creating a nuanced reality in which meaning well is not enough. One-sided perceptions of the world inevitably generate terrible actions.

This is by the nature of its subject matter a bloody and violent story. There is an element of fantasy throughout, but the flashy kung fu sequences also include death by sword, spear, and arrow. Soldiers and warriors clash, but old women and children also die. No amount of magical realism can transform or dilute the sad facts of this moment in history.

There are, nonetheless, occasional moments of humor. Yang’s light touch is evident throughout. The narrative glides along, propelled, rather than stalled, by plotting surprises. Panels come back to haunt the reader; almost none of them are superfluous or unconnected to later (or earlier) events. Convergences and synchronicities are introduced without fanfare, encouraging occasional epiphanies and melancholy realizations. It is a very satisfying read.

Yang’s artwork is delightful. Crisp, stylized…some have compared it to Hergé’s Tin Tin. It is simplified, not simple. Cartooning is often an art of reduction. Characters become icons. At the very least the artist creates a convenient visual shorthand…at best, he or she can convey—via just a few lines—the essence of what is drawn. For the reader, it’s almost like listening to radio—without a surfeit of information, you turn to the details supplied by the imagination. You recognize the symbolic drawing of Charlie Brown or Little Lulu, but you are free to create a real person in your mind. Yang renders each character distinctively, while his backgrounds are pared down to only what is necessary for the dramatic context. Nothing gets in the way of telling the story.

The coloring was done by Lark Pien, an accomplished artist and cartoonist in her own right. Both books have an extremely restrained color palette—browns, greys, muted yellows and pale blues. Saints even approaches looking monochromatic, like an old photo album. Perhaps this somber rendering signals that earthly life is not the main attraction, for, with very rare exceptions, it is only when mythological or religious figures appear that the hues become exuberant. Chinese opera heroes are ablaze with color, Vibiana’s visions of Joan of Arc come with a ghostly golden glow. Then again, perhaps the hushed coloring overall is simply in response to the grim events of the Rebellion.

In SAINTS, Vibiana has a vision of Joan of Arc at the crowning of Charles VII. Copyright Gene Luen Yang, used by permission of First Second Books.

As a strange little sidelight, I love the way Yang handled languages in the story. Chinese is written in English; other tongues, including English, are rendered as incomprehensible characters, which look like a meld of Japanese, Cyrillic, and Arabic. The reader inevitably feels some disorienting discomfort, a sense of being excluded from fully understanding the dialogue. This happens all through Boxers. It isn’t until entering the world of Saints that the strange characters are translated in boxes at the bottom of panels, and then it becomes clear that the letters actually form an alphabet, and, with some patience and close observation, it could have been decoded all along. A nice little reinforcement of a truth that I think Boxers & Saints contains.

So Yang doesn’t—or couldn’t—pick a side. What he does instead is show, via the various characters, the similarities between the two camps. Christ is very like Guan Yin, the Goddess of Mercy—both are paragons of compassion who are sacrificed for the sake of humankind. Joan of Arc shares the same aim as Ch’in Shih-huang, legendary first emperor and ruthless unifier of China—they want to unite their native countries. This is also the objective of Little Bao and Vibiana. The western soldiers behave like the Chinese Imperial troops and the elite Kansu Braves, dutifully following orders. The mercenary foreigners and the Chinese empress both shift allegiances and tailor their politics to protect their interests. Even Four Girl’s cranky and judgmental grandfather is like the ornery and judgmental priest Father Bey. It seems everyone is on a mission, from Bao to Vibiana to the missionaries to the foreign exploiters, and it is these agendas that prevent everyone from seeing the other as a fellow human being.

I recently attended a talk sponsored by the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund about comic books in libraries and schools being banned or challenged. I wondered, as I read Boxers & Saints, if challenges might be made due to the violence on its pages, even though the brutality is necessary to tell the story accurately. That would truly be shortsighted and unfortunate, for the clear outcome of the bloodshed in this graphic novel is sorrow, regret, and further savagery. Surely, in this often sad and bewildering time that’s a valuable message for young people to receive.

Pat Tong is a graphic artist and cartoonist in Oakland, California.

Fascinating review of subject and style of treatment I’m unfamiliar with. More please!