Theater Review: “King Lear” — Oregon Shakespeare Festival’s Monumental Achievement

Director Bill Rauch’s concept and the Oregon Shakespeare Festival company have, in a small space, created an achievement of monumental, yet personal, proportion.

King Lear by William Shakespeare. Directed by Bill Rauch. At the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, Ashland, OR, through November 3rd.

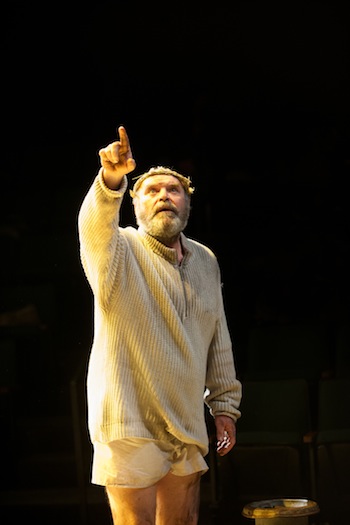

King Lear (Jack Willis) philosophizes on the heath in the OSF production of Shakespeare’s tragedy. Photo by Jenny Graham.

by Joann Green Breuer

King Lear, as every school child is instructed, is every inch a great tragedy. The royal whose first act error in judgement lets not only his kingdom slip away but also his kingship is inevitably subject to his ego and his expectations.The following acts pulsate with human failings, punctuated with loyal attendants, their wisdom unheeded or too late grasped. Action moves from palaces to wilderness, from actual ground to false cliff, from privilege to poverty, from elegant dress to naked flesh, from high life to helpless death, from artifice to spirit.

The task for King Lear’s director is daunting, and most directors have been daunted. So, what of Bill Rauch? Believe it or else, his vision matches his daring, and Shakespeare’s.

Rauch sets King Lear in the round, taking that wooden O, referred to in another stage-tale, seriously, and explores its intimate limits. We are privy to a multi-dimensional world, as this conceptually fluent production unfolds. There is nowhere to hide. The responsibility for making Rauch’s original, insightful imagery chillingly recognizable? A collaboration of the director with two aesthetically astute and technically prodigious designers: Christopher Acebo, sets, and Linda Roethke, lights.

Acebo pushes realism to its metaphorical resonance. Roethke continually illuminates the magic of the matter. Her bright light is emblematic of motivation, her chiaroscuro is mood in motion. Together Rauch, Acebo, Roethke, create a brave new but also recognizable world, and then give it room and rhythm to breathe.

A few specifics:

Lear at first at ease in a wide leather swivel chair, surveyor over all he holds sway; the King’s throne up a steep stairway, guard-able, removed; the map of Lear’s realm torn, destroyed by division; a later palace’s wrought iron gate slashes the stage in half; who’s is in and who’s out manifest, and despite their desperation, painfully equal.

Kent (Armando Duran), disguised, unmoustached, myriadly accented protector.

Gloucester (Richard Elmore), wire framed glasses, suit and tie, matter of (false) fact, proudly, myopically, conventional.

Edmund (Raffi Barsoumian), machismo-esque betraying brother, playing basketball with himself (he always wins); Edgar (Benjamin Pelteson), betrayed brother, slipping, sliding unclothed in the flies, above, confused witness, outside the ordered world, with only a slim railing as protection.

Fool (Daisuke Tsuji) circumspect, dignified, his costume a metastasis of duct tape, messages of warning, commitment, and ironic love stuck on his clothes.

Rauch casts two impressive actors as Lear. It is a massive role, in length and in breadth. By alternating performances, Rauch gives each actor opportunity to sustain necessary strength and stamina. Also, audience members have opportunity to compare interpretations. The versions of Lear are not that much different I am told, but one presentation is ten minutes longer than the other. The actors are: Jack Willis, whose work I have admired at the ART and elsewhere; and Michael Winters, whom I saw as Lear. I believe I did see Lear: white beard, hint of paunch, growing bewilderment gnawing at his hitherto customary confidence, a stifled cry of recognition finally wrenching his being to its essence. Not a moment of disbelief, the familiar lines spoken as if for the first time, and heard as if to listen is a gift.

King Lear (Jack Willis, right) finds the disguised Edgar (Benjamin Pelteson) strangely comforting. In the background, Lear’s Fool (Daisuke Tsuji) looks on in the OSF production. Photo: Jenny Graham.

A word about Cordelia (Sofia Jean Gomez):

With her purple streaked asymmetric bob, black lace décolleté, this goth/punk youngest daughter appears as a tough broad, no patience for her sisters or filial pieties. When she ultimately emerges in army camouflage it makes feminist sense. My only quibble is her tears in the first act. Yes, they are scripted, but I would think she would let slip a bit more surprise (dismay?) at her own delicacy than she displays.

Bill Rauch’s concept and his company have, in a small space, created an achievement of monumental, yet personal, proportion.

I am reminded of the genii in the lamp: its power to change the world is in its confinement.The right hand comes in contact with the container, and what one might wish for comes to mysterious radiance. Ay, here’s the rub.

Lear may no longer be king, but Rauch wears the crown.

For reviews of other OSF productions, go here.

Joann Green Breuer is artistic associate of the Vineyard Playhouse.