Book Review: “Left of the Dial” — Punk As Music and Philosophy

In these interviews, David Ensminger goes beyond questions of biography and discography to explore some of these artists’ more unlikely influences and their philosophies on not just punk, but life.

Left of the Dial: Conversations with Punk Icons by David Ensminger. PM Press, 320 pages, $20.

By Adam Ellsworth.

In the introduction to Left of the Dial, David Ensminger writes that his “journalism-meets-folklore” writings on the now decades old phenomena known as punk rock are not attempts to “undo the myths” or “tear down the walls” that are associated with the genre.

Instead, it is his intention to “recreate punk on a human scale, person-to-person, and ask questions that flow like ticker tape in the back of my mind.”

With Left of the Dial, he has succeeded.

To be sure, the book is not an attempt to tell the complete, or even incomplete, history of punk. It is essentially a collection of interviews with a handful of punk rock’s leading figures.

Some of these interview subjects might be a little obscure, even to the more enlightened music fan, but that’s one of the book’s greatest strengths. After all, we already know what Johnny Rotten/John Lydon thinks about everything, right down to his preferred brand of butter, but how often do we get such revealing, informative interviews from Captain Sensible of the Damned or Tony Kinman of the Dils?

While the likes of Ian MacKaye (Minor Threat, Fugazi), Jello Biafra (Dead Kennedys), and Mike Watt (Minutemen, fIREHOSE) will already be familiar to anyone who’s read Our Band Could Be Your Life, Route 666: On the Road to Nirvana, or just about any other book on punk/alternative music history, Ensminger goes beyond questions of simple biography and discography to unveil some of these artists’ more unlikely influences and explore their philosophies on not just punk, but life.

In some instances, this strategy of eschewing backstory in favor of getting under the surface does slightly backfire, however. For example, I was particularly confused while reading the interview with Jack Grisham of TSOL, a band I simply don’t know that much about. Once I did a little research on the band’s history and its various iterations though, I found what Grisham had to say pretty interesting. I just had to work for it.

But a little extra work never hurt anybody, and for the truly committed music fan, an invitation to dig deeper is always welcome.

Ensminger himself is certainly qualified to go deep on his subject. Not only is he a fan and longtime drummer, he’s also a Humanities, Folklore, and English instructor at Lee College in Baytown, Texas. As such, he approaches punk with both his head and his heart, and he understands that punk is not just a style of music but, at its best, also a way of life.

The politics of punk get as much play in Left of the Dial as the music does. While there are certainly right-wing punk bands (not to mention white supremacist/neo-Nazi punk bands), they aren’t what Ensminger is interested in. To him, and to the musicians he interviews, punk is an inclusive, and basically left wing, community. And while the interviews in Left of the Dial were conducted over many years, and in some cases first appeared in other publications (including Ensminger’s own fanzine, also titled Left of the Dial), this ideology is a thread that runs through the book from beginning to end.

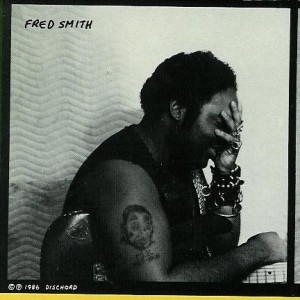

To his credit, that doesn’t mean Ensminger tries to paint a picture of punk rock as utopia. His interview with Fred “Freak” Smith, an African American guitarist who played with the DC band Beefeater, is particularly illuminating. “What was it like to be a black punk in DC?” Ensminger asks Smith during their Q&A. The guitarist responds,

Let us keep in mind that DC is what, 80 percent black, and this punk rock scene was fueled by angst-ridden white kids, a lot of whom I found out had fucking trust funds waiting for them when they became of legal adult age. Shit, I didn’t even know what a fucking trust fund was back then. It was very strange to be these “token negroes” playing in front of predominantly all-white audiences, but we did it. As Shawn Brown [singer of the DC hardcore band Dag Nasty] and myself will attest, there were fucking issues, man. A lot of fucking issues that we had to address when we did shows.

Interviewing Dave Dictor of MDC, Edminger asks, “Did you feel hardcore punk was less tolerant of gays?” to which Dictor responds,

It definitely wasn’t tolerant of gays on the whole. There were individual scenes that were more political and cooler; of course Austin, Texas, was probably as good and friendly of a scene and not as homophobic. We were very connected to the 1970s punk rock scene, which was more like a freak revolution than say, what started happening in the early 1980s, when a lot of younger kids got involved, like Minor Threat, SSD, and 7 Seconds. That was more like young guys in the crew that didn’t have a background in which they were into the Dead Boys or New York Dolls or into all that. That was one of the first divisions that we began to notice: people had different backgrounds. The original hardcore pioneers—Ian MacKaye, Kevin Seconds, most of those people per se—were not homophobic, but the fans they attracted [. . .] I would say were.

(In case you care about these things, it should be noted that Dave Dictor is not gay himself, but he has never hesitated to call people out for being homophobes.)

David Ensminger — he believes that punk is best when it’s open to as many different sounds and people as possible.

Obviously, no scene or musical genre is perfect. What’s interesting to Ensminger though is that there are always new bands coming along who are willing to use punk rock not just as a way to express themselves musically, but to create a more just world. The book ends with an email exchange between Ensminger and Thomas Barnett of Strike Anywhere, a band that formed in the late 1990s. As is often the case with email interviews, Ensminger asks long, wordy questions, and Barnett provides even longer, wordier answers, but at the heart of their conversation is the fact that punk can be a force for social change and that newer bands are part of a tradition that goes back not just to Fugazi, or The Clash, but to the pre-rock days of Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger.

“I remember reading an interview with Tad in Flipside in the early ‘90s,” Barnett writes to Ensminger, “where he said, ‘Punk rock is just urban folk music.’ I agree with that and raise him all of the subversive and independent arts, especially conscious underground hip-hop, garage bands, and dance punk hootenannies. Some of the hardcore electronic shit, too.”

These are of course Barnett’s words, but after reading Left of the Dial, I’m sure that Ensminger shares their sentiment. From the questions he asks to the musicians he chooses to interview, it’s clear that Ensminger believes that punk is best when it’s open to as many different sounds and people as possible, and when it’s rallying for a good cause—even if that cause is just to be free from boring, corporate rock and roll.