Theater Review: “The Merchant of Venus” — Shakespeare, Politically Corrected

This production of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice tries to have it both ways: a show about intolerance, bigotry, and hatred is set in a “politically correct” past.

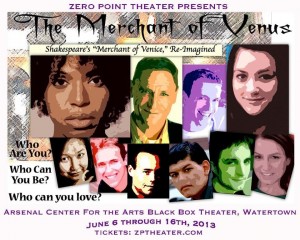

The Merchant of Venus (previously known as The Merchant of Venice) by William Shakespeare. Directed by Mark Bourbeau. Presented By Zero Point Theater. At The Arsenal Center for the Arts, Watertown, MA, through June 16.

By Ian Thal

Zero Point Theater’s production of The Merchant of Venus proclaims itself to be “Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice Re-Imagined.” But, outside of the change of name and a pun on the fact that one of Shakespeare’s original themes (itself a re-imagining of Giovani Fiorentino’s fourteenth-century tale) is the relationship between love and money, nothing much has been changed. Yes, there is a bit of unconventional casting, a deliberate change of milieu, and a few cuts in dialogue, but none of this tinkering is particularly unusual in contemporary productions of Shakespeare’s works. The only question is, on a dramaturgical level, do these “re-imaginings” make any sense?

The Merchant of Venice is one of the most problematic plays of the Shakespearian canon. It was, by the standards of the late sixteenth century, a romantic comedy. But because the villain of the piece, Shylock, is ripped directly from some of the more odious anti-Judaic folklore in circulation at the time, directors, dramaturgs, and Shakespeare fans, especially in the post-Holocaust era, have attempted to re-imagine the play as a tragedy and a plea for tolerance. In that, The Merchant of Venus does not stray far from the conventional desire to see Shakespeare as our contemporary.

The setting is a Prohibition-era, New Orleans-like city that resembles the Venetian Republic of the 1500s. Both are active seaports, prone to flooding; both are largely Roman Catholic cities renowned for their debauchery and carnival traditions. It is in this context that director Mark Bourbeau makes his most unconventional casting choice, by casting Miranda Craigwell as Shylock. As Phoebe Roberts’s production notes explain, “here Shylock is not just a Jew but also a woman, and not only a woman but also a black woman.” In short, rather than this being an example of race and gender-blind casting, this was a deliberate directorial/thematic choice.

Of course, there are Jews who are women, Jews who are black, and Jews who are black women. The question is whether or not making Shylock specifically a black woman works on stage. Craigwell is certainly a fine actor with a strong facility with Shakespearian meter and the sort of physicality needed to embody the language. She understands both the virtues and the flaws of her character and plays Shylock with both dignity and intelligence as well as arrogance and rage. So as an acting exercise, it works.

Dramaturgically, however, the switch makes little sense. Shakespeare’s language is shot through with so many references to sexual organs and reproductive activity that careful attention must be paid if the gender of a major character is changed. Solanio’s cruel jests about Shylock’s testicles: “two sealed bags of ducats,” and “jewels, two stones, two rich and precious stones, stol’n” by Jessica when she eloped with Lorenzo, as well as his taunts at the moneylender’s penis, when he suggests Shylock is unable to maintain an erection (“Out upon it, old carrion! Rebels it at these years?”), are rendered nonsensical when hurled at a woman. Zero Point’s production adjusts gendered words elsewhere in the script, such as substituting “mistress” for “master.” But only the most superficial aspects of the gender-bending were addressed.

Another example that making Shylock a woman becomes problematic is Launcelot Gobbo’s line, addressed to Jessica, “if a Christian did not play the knave and get thee, I am much deceived.” Launcelot is attempting to explain how he can have affection for the daughter of the villain—by suggesting that Jessica is not the daughter of Shylock but the fruit of an illicit relationship. Zero Point’s Shylock gave birth to Jessica: whether or not she was loyal to her late husband is irrelevent. The awkward redaction that follows, in which Jessica denies being adopted, does not solve the problem because that is not what Launcelot is suggesting.

Making Shylock’s skin color an additional signifier of her marginalization is probably less problematic than the change of sex—or would have been if Zero Point had decided to go for some consistency in casting or chosen a different milieu. Tubal, Shylock’s fellow Jew, played by Jeffery Chrispin, is also black. However, Shylock’s daughter, played by Ying Songsana, is clearly of East Asian ancestry. This would not be a problem if the production chose racially-neutral casting across the board, but in granting race dramaturgical centrality in this “re-imagining,” we are again being given something that doesn’t add up, especially given that the play is to set in the pre-Civil Rights era American South.

This also necessitates the dropping of yet another exchange, when Lorenzo scolds Launcelot for impregnating “the Mooress,” a servant at Portia’s Belmont estate. (These lines were also dropped in Theatre for a New Audience’s 2007 production and 2011 revival—in part because their Launcelot was black.)

Even if Jessica has become a Christian, how would Lorenzo’s upper-class, Southern white friends possibly accept into their homes the formerly Jewish, Asian daughter of a Black Jewess who has the chutzpah to rail against the injustices they commit? Portia and Gratiano both relish any excuse to express a racist sentiment—both are eager participants in Shylock’s humiliation, so the notion that Lorenzo’s friends might be progressives in an otherwise unjust era in American history cannot be supported by the text.

This production tries to have it both ways: a show about intolerance, bigotry, and hatred is set in a “politically correct” past.

These problems are, of course, part of the history of the text. Shakespeare, a renaissance humanist, could have empathy for the most villainous of his characters, but ultimately, he was a writer whose knowledge of Jews was most likely limited to the anti-Judaic folklore and sermons of his era. As an Englishman, he most likely never knew a Jew personally, as England had been ethnically cleansed of its Jews in 1290 and those who did live in England in the 1590s would have feigned Christianity—they had the example of the execution of Doctor Rodrigo López as a warning of what could happen if they were even suspected of being Jews. Audiences in the 1590s would have also understood Shylock’s forced conversion to Christianity as a happy ending.

Despite the dramaturgical muddle, Bourbeau does make some strong directorial choices in a number of places. A wordless sequence in between acts III and IV has Portia binding her breasts as she prepares to disguise herself as the learned Doctor Balthazar. An early scene has Antonio (Cliff Black) looking longingly at the frolicking of the younger male characters, his eyes meeting those of Bassanio (Will Jobs). Director and actors deserve to be commended for playing the homoeroticism between Antonio and Bassanio, an aspect of the play frequently handled only superficially, if at all, in most productions. Black plays Antonio as pokerfaced with regards to his affections. Jobs presents Bassanio as a young man who plays on his good looks to get what he wants and what he needs. By the trial scene, it is evident that Bassanio’s affections are genuine and not just the pragmatic nurturing of a sugar-daddy.

Unfortunately, the coupling of Bassanio and Antonio was the only convincing romantic pairing in this production. Jobs’s Bassanio has little chemistry with Anneke Reich’s Portia, and Josh Coleman’s Lorenzo and Songsana’s Jessica never seemed to connect at all.

Reich plays Portia as a giddy ingenue, rather than what Shakespeare wrote, a precocious (and racist) intellect stunted by society’s limitations on women. This approach makes Portia’s performance as Balthazar in the courtroom scene and her status as the object of Morocco and Aragon’s affections unconvincing (though perhaps less problematic for Aragon, since he is characterized as a fool). Perhaps they are submitting themselves to the demeaning trial of the three chests for her money? Je-Kori A.K. Salmon plays Morocco as a failed seducer trying to get into Portia’s knickers rather than an arrogant warrior-prince concerned about making a comfortable (and lucrative) marriage.

Mary C. Ferrara, on the other hand, plays Nerissa, the maid, with an aristocratic bearing and intelligence that is more fitting for her mistress (she is also far more impressive as Balthazar’s clerk than Reich is as Balthazar), which also makes her mismatched when paired with Gratiano.

The original music by Thomas Blanford was compelling, and the live band of Kate Lyczkowski (keyboards), Julianne Johnston (alto), and, on the night I attended, Jane Wang (bass) was equally strong.

Most of Kelley Feetham’s costuming kept to the 1920s setting for both the male and female characters—the major oddity was Shylock wearing a tallit gadol in court. The tallit gadol, or prayer shawl, is worn by Jews only during prayers (the tallit katan is a different article of clothing). It is not appropriate when conducting business with gentiles or attending a secular court. Furthermore, while it is not so unusual for women, especially those associated with the Conservative, Reform and Reconstructionist branches of Judaism, to wear a tallit today (and indeed, there is both historical precedent for, and rabbinical opinion in support of, women choosing to wear tallit during prayers going back to the medieval period), it would have been strange to most Jews in the 1920s. Even if we overlook the anachronism of a woman wearing a tallit in a secular courtroom in the 1920s, the fact that she is wearing head covering at all times, except when she is wearing her tallit, is another non-sequitur.

Unfortunately, just as Shakespeare’s texts are shot through with themes, variations, and ironies, Zero Point Theater’s production is shot through with half-baked ideas that obfuscate rather than illuminate the text.