Visual Arts Review: Seeing the Wonders of Diaghilev and The Ballets Russes

This exhibit dedicated to Diaghilev and The Ballets Russes is well worth a trip to Washington D.C. because of the amazing objects on display, even though the mounting at The National Gallery of Art takes a more conventional museum approach, lacking the dynamism of the three-dimensional experience provided by the V&A in London.

Diaghilev and The Ballets Russes, 1909-1929: When Art Danced With Music. At The National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., through September 2.

By Iris Fanger

Pablo Picasso, Harlequin (Portrait of Léonide Massine), 1917. Photo: 2012 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The curatorial vision shaping this huge exhibition about the Diaghilev Ballets Russes (DBR, 1909–1929) changed when the show crossed the Atlantic from London’s Victoria & Albert Museum to the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. In London, the proliferation of costumes, set designs, photographs, films, ballet slippers, and back stage paraphernalia, housed in the grandma’s attic that is the V & A, was mounted under stage lights and partially on a moving turn-table. The purpose, according to Tim Hatley, the scenic designer who served as consultant to Jane Pritchard, the V & A dance curator who masterminded the display, was “to bring the theatricality and excitement of living artists into the exhibition.” The September 2010-January 2011 exhibit marked the 100th anniversary of the company’s debut in Britain.

Not so in Washington for the current version, Diaghilev and The Ballets Russes: 1909-1929: When Art Danced With Music, although the effect is equally splendid. The National Gallery adds works and objects to the London exhibition, emphasizing the achievements of the visual artists who labored for impresario Serge Diaghilev throughout the 20-year lifetime of his itinerant troupe. Rather than pictured on moving bodies, the variety of costumes on display here stand in static grandeur, impressing the viewer with their imaginative designs and magnificent workmanship. (“Workwomanship” might be a more accurate noun because many of the artisans were females who embellished the fabrics with embroidery, appliqués, and other decorative techniques.)

Natalia Goncharova, Design for the back cloth for the final Coronation scene from The Firebird, 1926. Photo: V&A, London.

One only has to see the long, velvet cape worn by the magician Köstchei for the 1926 revival of The Firebird, designed by Natalia Goncharova, embellished with golden threaded rays of the sun and huge appliqués of mysterious symbols (Dansmuseet—Museum Rolf de Mare, Stockholm) or the magnificent, highly colored, clinging gown worn by the title figure in Cleopatre (Los Angeles County Museum of Art) from the 1918 revival of the ballet, designed by Sonia Delaunay, to appreciate that a costume can be as distinctive a work of art as a painting or a sculpture.

As noted above, the National Gallery borrowed widely from collections throughout the world, although the majority of the objects on display are from the V&A exhibition. A number of striking works were added, spread through multiple galleries over two floors of the East Wing. Many of these items are from the Wadsworth Athanaeum in Hartford, which purchased Serge Lifar’s collection in the 1930s, including costume and set designer Leon Bakst’s rose-petal-covered leotard and headpiece, created for Nijinsky in The Spirit of the Rose. The latter is displayed on a mannequin arranged in a flying leap, an attempt to remind viewers of the dancer’s famous exit through a window in the backdrop for the ballet. Lifar, who sold much of his collection to Hartford when he was strapped for cash during a tour of the USA, was DBR’s lead male dancer during its final years and one of Diaghilev’s lovers. The Harvard Theatre Collection loaned a number of watercolor costume designs by Bakst.

Max Weber, Russian Ballet, 1916 (oil on canvas). Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of Edith and Milton Lowenthal.

The Diaghilev Ballets Russes was surely the most important artistic organization in the western world during the years leading up to and after World War I, collapsing only with its namesake’s death in 1929. A pick-up company of Russian dancers on vacation from the Imperial Theatres in St. Petersburg and Moscow performing short works by Mikhail Fokine, DBR created a furor at its Paris 1909 premiere, a testament of Diaghilev’s genius as an arts entrepreneur. He was a wizard at discovering talented young choreographers, performers, designers, and composers and combining their talents to produce new and daring ballets that dazzled audiences in Europe, Latin America, and the United States (1916–1917) when the company made two coast to coast tours. (Due to the vagaries of palace politics, reinforced by the coming of World War I and the Russian Revolution, DBR never performed in Russia).

Among the names associated with DBR that reverberate far beyond dance history are Vaslav Nijinsky and Anna Pavlova; Igor Stravinsky, Claude Debussy, and Serge Prokofiev; the Russians, Alexander Benois, Bakst, Nicholas Roerich, Goncharova, and Michel Larionov; not to mention Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Georges Roualt, and Coco Chanel, only latter only a sampling of the Europeans whom he enlisted. Picasso was so entranced by the experience that he married Olga Khokhlova, one of the dancers. Two portraits of his wife are included in Washington, along with his portrait of Leonide Massine, the company’s choreographer during World War I and again in the mid-1920s. Fokine, Nijinsky, Bronislava Nijinska, and George Balanchine, the successive resident choreographers, are of less importance in this exhibit, recalled by the film snippets of their ballets that are sprinkled through the exhibition. In contrast, Nijinsky as a performer is heavily represented. One of my favorite displays is the pair of dangling, pearl earrings he wore as the slave in Scheherezade.

Natalia Goncharova, Costume for the sorcerer Köstchei from The “Firebird”, 1926. Photo: 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York/ADAGP, Paris.

Most overwhelming are the two enormous drops, conserved from the actual productions, that are hung in the exhibition: the backcloth by Goncharova for the final Coronation scene in The Firebird (1926) and the front cloth executed by Alexander Schervashidze for The Blue Train after a painting by Picasso (1924) and used ever after for the company’s performances. Equally valuable is seeing the collection of oil paintings and sculptures by artists influenced by DBR and gathered for this exhibition from numerous museums. Among them are Jacques-Emile Blanche’s wall-size painting of Nijinsky in Siamese Dance (Getty Collection), Malvina Hoffman’s small sculpture of the faun of Afternoon of a Faun (The Tobin Theatre Arts Fund), the American Max Weber’s painting, Russian Ballet (Brooklyn Museum), Amedeo Modigliani’s Portrait of Leon Bakst (National Gallery of Art), and Fernand Leger’s Exit the Ballets Russes (Museum of Modern Art, New York).

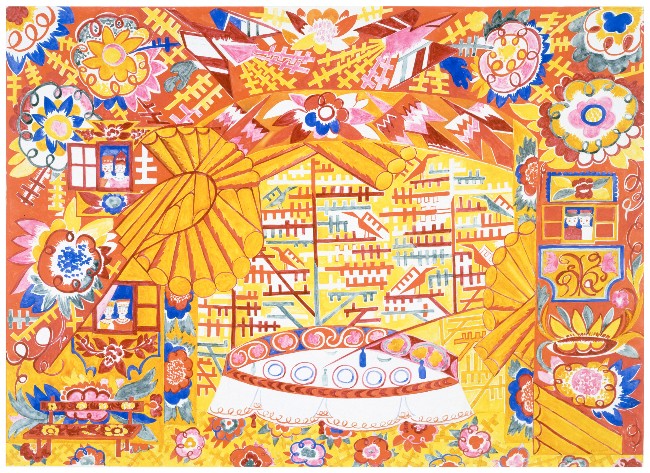

Natalia Goncharova. Set design for The Golden Cockerel, 1914. Photo: 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York/ADAGP, Paris. Photo © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

This exhibit is well worth a trip to Washington D.C. because of the amazing objects on display, even though the mounting at The National Gallery takes a more conventional museum approach, lacking the dynamism of the three-dimensional experience provided by the V&A in London. If you go be sure to check out the “Diaghilev Lunch,” a buffet offered in the Garden Cafe of the West Wing.

Note: The National Gallery produced an engrossing 55-minute film on the exhibition, available for purchase ($19.95) from the gift shop at National Gallery of Art, along with the catalogue from the V&A show that has added a new essay by Ms. Pritchard ($40. PB).